Kevin Madigan of the Harvard Divinity School says Christians should not assume that there is something about Islam that is intrinsically violent, anti-Semitic and anti-modern. After all, we’ve been there, done that.

Violent. Illiberal. Intolerant. Anti-Semitic. After the tragic, murderous events in Paris earlier this month, these adjectives have been applied not only to murderous jihadists but to Islam itself. Yet these words could just as easily apply to medieval Christianity and to much of Christianity in the 20th century.

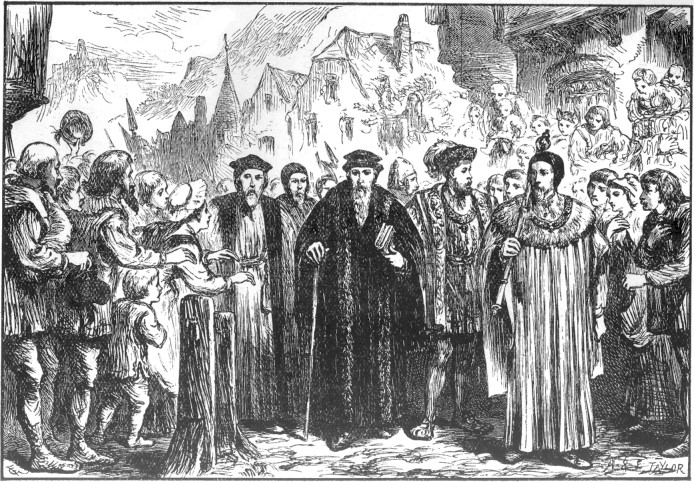

Medieval Christians notoriously persecuted, incarcerated and burned religious dissenters. Less well-known is that Protestant Reformers in early modern Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, despite their differences with the old Western church, agreed that religion was not a matter of private judgment but of deep communal concern and unitary. Reformers believed that religious orthodoxy must be safeguarded, and almost all agreed that dissidents deserved severe punishment and even death. Calvin’s Geneva was a theocracy; one theologian who doubted the Trinity was burned to death — with Calvin’s approval.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, popes habitually fulminated against modernity. One reason that popes like Pius XI (1922-39) supported the fascist dictator Mussolini — he once stated that Il Duce had been sent by “Providence” to rescue Italy — was that they shared antipathy for parliamentary democracy and for freedom of the press and association. Generally speaking, sacred and secular leaders in Catholic parts of Europe loathed modernity and all it represented: liberal democracy, emancipation, tolerance, separation of church and state and freedom of thought.

Only in the early 1960s did the Roman Catholic Church reject this medieval worldview. Only then did it begin to tolerate other world religions, representative democracy and the disenfranchisement of religion. It was only recently that it started to be reluctant to use political agencies to achieve religious objectives — even to accept the idea that the modern citizen is free to be nonreligious.

Modernization took a long time for Christianity. Maybe it could happen more quickly with Islam?

We can only hope that, with the quickening pace of historical change in modernity, Islam can adjust more rapidly than Christendom, so that a broad-minded form of the religion will prevail. Muslims will have to recognize what the West, through many centuries of hard experience and reflection, has learned: that religious texts arose in a particular context and must be reinterpreted in the new context of modernity; that pluralism within one’s own tradition and the tolerance of other faiths must be appreciated anew; and, finally, that the coercive imposition of faith will generate only nominal or hypocritical, not authentic, conversions.

This will require patience on the part of the West, and more. Above all, the West must not panic and extend its battle with radical Islam — most of whose victims have been Muslims — to the world-wide population of Muslims. The Christian world passed through its era of repression and theocracy; there is no reason to presuppose that the Islamic world cannot do likewise.

Posted by Andrew Gerns