John Bartram Rhem had Parkinson’s disease and was ready to die. But his doctor could neither assist him in his death nor have the conversation about end of life care beyond attempts to manage the pain and offer physical support. In the end, he decided to refuse nutrition and hydration in any form and died ten days later.

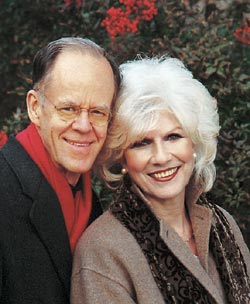

His wife, NPR talk show host Diane Rehm talks about her experience caring for her husband during his final days and the need to open the conversation about end of life care, including the right to die, in a new book “On My Own.”

Religion and Ethics Newsweekly:

The Rehm’s attended the Episcopal Church, and John recounted his own spiritual journey in his own book “Onward Journey: Seeking the Divine.”

The Rehm family was not always religious. The couple’s two children were baptized in the Syrian Orthodox Church. (Diane’s parents emigrated from the Middle East.) But John was not religious for much of his life. The two met in 1958, when he was a lawyer at the State Department and she was a secretary.

John humored his wife and attended St. Patrick’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., a church that appealed to the couple because of its involvement in the civil rights movement.

Years later, John had a conversion experience. He walked out of New York’s St. Thomas Church “a new man and Christ’s own,” as he described in his own memoir, “Onward Journey: Seeking the Divine.”

It was “as though for all of his adult life he had been fighting against the idea of belief in God, or Christ,” Diane said.

But John’s illness interrupted their participating in the parish.

The Episcopal Church is officially opposed to doctor-assisted dying (also called assisted suicide), passing resolutions in 1991, 1994, and 2000.

In 1996, The Diocese of Newark issued a report on Assisted Suicide, saying that it may be morally acceptable for terminally ill persons to end their own life. The report set out seven criteria:

- the decision to hasten death is a truly informed and voluntary choice free from coercion

- a person’s condition is terminal or incurable

- pain is persistent and progressive

- all other reasonable means of amelioration of pain and suffering have been exhausted

- the decision to end one’s life has been discussed with significant others

- the method and timing of death have been clearly discussed and understood by the patient

- the plan for voluntary assisted death places maximum autonomy and command of the process in the hands of the dying person

The Pew Forum, in a summary of various religious traditions teaching on the subject, summarizes the Episcopal Church’s stand in this way:

In 1991, the Episcopal Church passed a resolution against assisted suicide and other forms of active euthanasia, stating that it is “morally wrong and unacceptable to take a human life in order to relieve the suffering caused by incurable illness.” According to Timothy Sedgwick, a professor of Christian ethics at Virginia Theological Seminary, this teaching comes from the church’s broader view “that one should never take a life, even your own.” At the same time, Sedgwick says, there is a sense within the church that hard-and-fast rules on end-of-life issues may not fit every circumstance. “Although we have a clear moral norm against the taking of human life, there may be cases that stand beyond judgment,” he says.

The church also teaches that it is justified to stop medical treatment, including artificial nutrition and hydration, when that treatment brings significantly more burdens than benefits to a person. Such decisions also should be informed by the moral norm against taking life, Sedgwick says. “The dividing line here is the difference between the intent to take life and withdraw[ing] treatment.”

According to Ms. Rehm’s account, her husbands choice to withhold nutrition and hydration appears to be consistent with the 1991 General Convention resolution, but it may have been a decision of last resort. The press reports, interviews, and news releases do not indicate what role, if any, pastoral care played in his decision to withhold treatment.

Rehm said she decided to write the book because she was frustrated by the way her husband died.

“People need to talk about this issue,” she said. “Doctors need to be taught about this issue. The whole idea of doctors being taught about helping to keep people alive, but not being taught how to listen to those who are ready to die — that seems to me sad and misguided.”