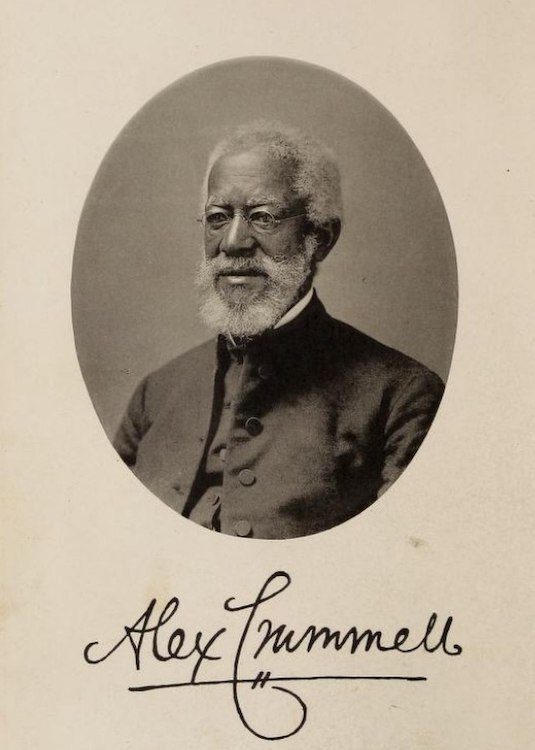

Readings for the feast of Alexander Crummell, 2021:

Psalm 19:7-11

Sirach 39:6–11

Mark 4:21-25

Mark reveals that in the fullness of time, all that is hidden shall eventually be revealed. Although racism and prejudice tried to hide the light of Alexander Crummell, his light still shone, and still shines today in our feast calendar.

Alexander Crummell was born in New York City in 1819, the son of a former slave and a free mother. His grandfather, a member of the Temne tribe, was captured in Sierra Leone and sold into slavery at age 13. Both his parents were active abolitionists and, because of easily traceable roots in their African heritage, instilled a deep and abiding sense of connection to the African continent in young Alexander. Although Alexander’s father, Boston Crummell, could not read or write, he saw to it that his children received the best education he could afford for his children, through schools associated with the abolitionist movement and private tutors. Post-high school, he enrolled in Noyes Academy in New Hampshire, and it was there he had his first brush with the dark forces of racist society, even in “free” states. On July 4, 1835, he and several of his classmates gave rousing pro-equality speeches at an Independence Day gathering organized by abolitionists in Plymouth, Massachusetts. A little over a week later, an angry white mob destroyed Noyes Academy.

Crummell felt the call to priesthood in the Episcopal Church, and, like many of his era would have done, applied to General Theological Seminary in 1839. He was denied entrance on account of his race. Thanks to some connections through his abolitionist work in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, he read for Holy Orders and was ordained a deacon in 1842 and a priest in 1844. He quickly discovered that the struggle to become ordained was simply a step towards another struggle–he quickly realized (in his own words) “there was little scope for black priests.” Feeling he was languishing in Providence, Rhode Island, he approached the Bishop of Pennsylvania, Henry Onderdonk, about the possibility of expanding a black Episcopal presence in Philadelphia. Bishop Onderdonk’s reply was, “I will receive you into this diocese on one condition: No negro priest can sit in my church convention and no negro church must ask for representation there.” Crummell turned his “offer” down.

Alexander Crummell then turned his attention to England, first, to raise money for his congregation by lecturing on abolitionism. This eventually led him to return to England to study at Queen’s College, Cambridge, and continue to support himself on the lecture circuit. It was during this time he became involved in the controversial Pan-African movement, around the same time some free African-Americans were moving to Liberia as part of the movement. The English climate had taken a toll on Crummell’s health, and he became a missionary there in 1853. Once in Liberia, he found himself in a thorny place. As someone only two generations from an indigenous African ancestor, he found himself empathizing with the plight of the native tribes, and at odds with the colonial attitudes of the Americo-Liberians involved with governing the former colony. At the same time, his own colonial attitudes about Christianity (namely, that the indigenous people needed to be Christianized), put him at odds with tribal groups. By 1872, fearing his life was in danger, he returned to the United States, establishing St. Luke’s Church in Washington, DC. In 1883, as a response to some bishops proposing missionary dioceses for African-American churches, Crummell founded the organization that would eventually become the Union of Black Episcopalians.

Crummell’s greatest light, though, was that through all these changes, all these moves, all these convolutions in his own life, he remained a lifelong scholar, author, and teacher of moral philosophy in a number of academic posts during his career. His work in moral philosophy would be the foundation of other great African-American thinkers such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Henry P, Slaughter. He was able to stake a moral foundation for the equality of all races despite all the barriers slavery and Jim Crow threw at him.

Alexander Crummell still managed to let his light shine, even when the bushel baskets filled with the sin of racism surrounding him, tried to hide or extinguish his light. What might we do to ensure the light shines even more brightly?

Image: Alexander Crummell, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri , presently enjoying being a “free range priest” until her next interim assignment.