For many decades now, throughout most dioceses and many institutions of the Episcopal Church, anti-racism efforts have been an important part of Episcopalians striving to fulfill our Baptismal Covenant promise to “respect the dignity of every human being.” In February, the Episcopal Café covered the most recent work of The Executive Council Committee on Anti-racism (ECCAR) meeting. But how effective have these efforts been in an Episcopal Church largely led by white clergy and lay leaders and in dioceses whose very financial foundation is directly tied to the legacy of chattel slavery? How willing are white Episcopalians, especially those with economic and political power at the parish level and diocesan levels, to face difficult truths about the intersection of economic and racial violence done largely by white Americans in our own communities and abroad? How might that lead to repentance?

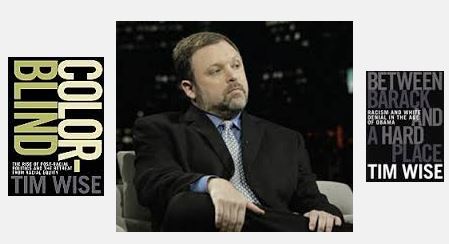

In a recent essay Tim Wise, a white anti-racist educator and author, challenges white Americans -especially those with power and economic advantage-by holding up a mirror to white America and challenging mainstream media coverage of reactions to the recent uprising in Baltimore:

It is bad enough that much of white America sees fit to lecture black people about the proper response to police brutality, economic devastation and perpetual marginality, having ourselves rarely been the targets of any of these. It is bad enough that we deign to instruct black people whose lives we have not lived, whose terrors we have not faced, and whose gauntlets we have not run, about violence; this, even as we enjoy the national bounty over which we currently claim possession solely as a result of violence. I beg to remind you, George Washington was not a practitioner of passive resistance. Neither the early colonists nor the nation’s founders fit within the Gandhian tradition. There were no sit-ins at King George’s palace, no horseback freedom rides to affect change. There were just guns, lots and lots of guns.

We are here because of blood, and mostly that of others; here because of our insatiable and rapacious desire to take by force the land and labor of those others. We are the last people on Earth with a right to ruminate upon the superior morality of peaceful protest. We have never believed in it and rarely practiced it. Rather, we have always taken what we desire, and when denied it we have turned to means utterly genocidal to make it so.

Which is why it always strikes me as precious the way so many white Americans insist (as if preening for a morality contest of some sorts) that “we don’t burn down our own neighborhoods when we get angry.” This, in supposed contrast to black and brown folks who engage in such presumptively self-destructive irrationality as this. On the one hand, it simply isn’t true. We do burn our own communities, we do riot, and for far less valid reasons than any for which persons of color have ever hoisted a brick, a rock, or a bottle.We do so when our teams lose the big game or win the big game; or because of something called Pumpkin Festival; or because veggie burritos cost $10 at Woodstock ’99 and there weren’t enough Porta-Potties by the time of the Limp Bizkit set; or because folks couldn’t get enough beer at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake; or because surfers (natch); or St. Patty’s Day in Albany; or because Penn State fired Joe Paterno; or because it’s a Sunday afternoon in Ames, Iowa; and we do it over and over and over again. Far from mere amateur hooliganism, our riots are indeed violent affairs that have been known to endanger the safety and lives of police, as with the infamous 1998 riot at Washington State University…

On the other hand, it is undeniably true that when it comes to our political anger and frustration (as contrasted with that brought on by alcohol and athletics) we white folks are pretty good at not torching our own communities. This is mostly because we are too busy eviscerating the communities of others—those against whom our anger is aimed. In Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Panama, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Manila, and on down the line.

When you have the power you can take out your hatreds and frustrations directly upon the bodies of others. This is what we have done, not only in the above mentioned examples but right here at home. The so-called ghetto was created and not accidentally. It was designed as a virtual holding pen—a concentration camp were we to insist upon honest language—within which impoverished persons of color would be contained. It was created by generations of housing discrimination, which limited where its residents could live. It was created by decade after decade of white riots against black people whenever they would move into white neighborhoods. It was created by deindustrialization and the flight of good-paying manufacturing jobs overseas.”

Ahead of the 2015 General Convention in Salt Lake City, how might white Episcopalians join in solidarity with African-Americans in the Episcopal Church and in the world for racial reconciliation and economic justice as it once did under the leadership of Presiding Bishop John Hines during the General Convention Special Program of 1969? What might the 2015 General Convention do differently to learn from the mistakes of Episcopalians in 1969?