by Linda Ryan

In the gospel stories the story doesn’t end–writers leave it to us to figure out what happens afterwards. What happens? Where are we in the story? — unknown

Summers when I was a child were usually marked with Vacation Bible School. I remember the one- to two-week sessions, complete with learning songs, doing crafts, memorizing Bible verses, Kool-Aid, cookies, and lots of Bible stories. The Bible stories were the main event of the day, quite often the familiar stories from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament as well. All of them had a moral or ethical (or theological) point we were to think about and then use what we learned in our own lives. We didn’t get any of the stories like Jephtha’s daughter, the sacrificed concubine, the murder of Uriah, or any one of a number of others, but somehow the horror of Noah’s Ark or the Akeda disappeared in rainbows, replacement rams, and evidence of God’s love. It worked. We believed it.

The older I get, the more I realize that what I learned then wasn’t the whole story. It began to feel like a Reader’s Digest version–I had gotten the meat of the story, but there were still the skin and bones that were missing. It’s a bit hard to explain, but it felt like I needed to know what was before the beginning of the story. Oh, sure, most of the time there’s some buildup to the story, something about the time or place or people, but often that’s not quite enough. What’s more important to me, though, is what happened after the story.

Look at the parable of the Good Samaritan. The run up to the story is the introduction of the Jew who was on his way from here to there but who ran into robbers on the way. We know the part of the story where people passed him by, and then came the Good Samaritan who picked him up, brought him to an inn to be cared for. The Samaritan then went on his way, promising to return to pay for whatever other needs the injured man had required. It’s a very familiar story, and one with a great moral, but I can’t help but wonder why the Jew was traveling. Why was he alone? Most people traveled at least in pairs if not larger groups because there was safety in numbers. Was his traveling alone that made him a tempting target, or did he have something obviously worth stealing? Or was it simply because he was a Samaritan? So it was a parable, probably not a real event; however, that doesn’t make it less valid for questioning.

A second question that comes to mind with this story is what happened afterwards? Did the Samaritan return as he promised? And what about the injured man? Did he recover? Did he go on with his life? Did he repay the man by helping someone else? If he did, was it someone who was not of his faith? Again, the parable doesn’t say; the important part of the story had already been told.

A third question is where am I in this story? What character most draws my attention or what part of the scene represents where I am now in relation to the story? What would I do? What would I learn from the situation? How would it affect my life?

The gospel writers wrote down the bare bones, telling enough of the story or parable to get the point across, but there was no need for elaboration or “What happens next.” The people knew the area, the risks, the daily life that the stories contained but without description that would be what we expect today. The writers’ main job was to present stories of miracles and the teachings of Jesus to people who had probably not heard him preach or who came to the faith after his death. They were written for a purpose, and that purpose was not pure entertainment.

We are used to endings like “And they all lived happily ever after,” even though most of our books no longer leave us with that kind of conclusion. Certainly in the Bible the endings were often far from happily ever after. Although many stories like those featuring healing certainly point to a kind of happily ever after, the healing is always a way to point out Jesus’s mission and the glorification of God. That was the whole reason for their writing, not to be like CNN reporting or some sort of social study of the result of Jesus’s actions.

Just because the writers had a specific task in hand does not preclude our thinking about and using our imagination to get deeper into the stories. Take the woman with the hemorrhage. She had spent all she had on doctors who couldn’t cure her, but Jesus did. What happened to her afterwards? She apparently had no male relatives, she no longer had wealth to keep her, so what happened to her? How did the rest of her life go? The same with Jarius’s daughter who shared the same story. After her miraculous recovery, did she go on to live a happy life, marry well, and have many children to hear the story and believe in Jesus’s power? It’s to be hoped that she did. We’ll never know for sure.

Life is a series of stories for each of us, but, unlike the gospel writers, the stories fall on a timeline. They have a beginning, an action, an end, and then life continues, sometimes on the basis of the events of the story. Perhaps we saw or were part of a traumatic and tragic event that radically changed the pathway of our lives, or perhaps we saw or heard something that someone said that changed us in some small but significant way. The event might be over, but because something intervened, life goes on a different tack than it would have otherwise.

Try putting yourself in the story. If nothing more, it will be a good exercise in imagination, a gift God gives us to inspire our creativity and stretch our thinking. But there is always a chance of that exercise bringing us new insights, new thoughts, new beliefs, that will take us on a whole new track. It might change our lives–and then, it might just help to change the world.

Linda Ryan co-mentors 2 EfM Online groups and keeps the blog Jericho’s Daughter. She lives in the Diocese of Arizona and is proud to be part of the Church of the Nativity in North Scottsdale.

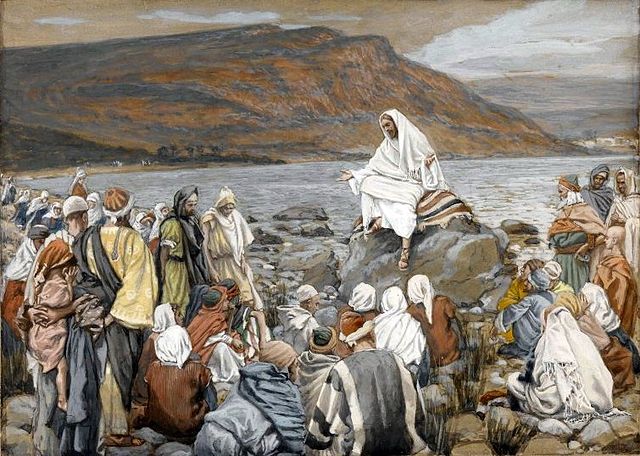

Image: Jesus teaching his disciples by James Tissot – Online Collection of Brooklyn Museum; Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 2006, Public Domain