In the aftermath of last week’s election, many people have begun wearing safety pins as a statement of solidarity for marginalized people. This has become controversial, as many activists feel that it is an empty gesture that only makes the wearer feel good without actually helping others. However, some have reported stories of feeling safer seeing other people wearing safety pins. Ultimately the consensus is that the pin itself is not sufficient, and that actions of direct support must also happen.

The idea of wearing a safety pin in solidarity began in the United Kingdom after Brexit (the vote for the UK to leave the European Union). In the wake of the vote, hate crimes against immigrants spiked. In an attempt to counter that, a woman started the movement, hoping that the inexpensive and innocuous pin would make more people be able to join in. “For those wearing it, it would be a constant reminder of the promise they’ve made not to stand idly by while racism happens to someone else,” she told the Metro. There was immediate push back though, because it did not translate to much actual activism. The initiative did not gain much momentum in Britain. Edited to add: The safety pin movement in the UK was inspired by the #Illridewithyou movement that sprang up in Australia during and following a hostage situation in Sydney in 2014.

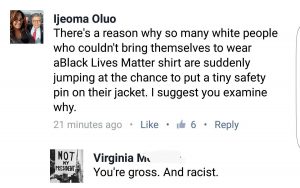

However, here in the US, it has caught on much more widely, with people also changing their profile pictures to safety pins. Even as the symbol’s popularity grew, activists decried it as “back patting” on the part of white people, a way to make themselves feel better without actually doing the work of dismantling the systems of oppression that marginalized people face. Ijeoma Oluo, a well-known and outspoken writer, tweeted that people who “couldn’t bring themselves to wear a Black Lives Matter shirt” were all too excited to wear a safety pin.

She faced a backlash from hundreds of people, who said she was racist, divisive, and “part of the problem.” In a follow up article, Oluo said, “None of the commenters seemed to be aware that telling a black woman that she was wrong to question white people is kind of the opposite of racial solidarity in a country where the majority of white voters just elected Trump.”

Furthermore, people of color have voiced the concern that this simple symbol is easily worn by white supremacists and others, meaning that marginalized people cannot, in fact, trust that the person wearing a safety pin is an ally. In an article on Medium, Lara Witt wrote, “the problem with hyper visible forms of allyship is that they can easily be co-opted by white supremacists in order to harm people of color.” Isobel Debrujah, a prominent blogger, found an image from a white supremacist site actively encouraging their members to wear safety pins as solidarity for their own movement. People are encouraged to make their safety pins a more overt sign of support with rainbows, Black Lives Matter tags, etc., things that bigots would not be willing to wear.

On the other hand, many people have pointed out that wearing a safety pin is not necessarily an empty gesture. They are calling for a more positive approach, encouraging those wearing safety pins to more direct activism. A lot of people are new to outright protest, and feel shamed and excluded by what they feel is a “holier-than-thou” attitude from more experienced protesters. Kristin Fontaine, a writer here at the Cafe said, “I can feel the fear of doing activism wrong creeping in already. I can feel myself retreating from my ideas because I’m afraid I’ll mess up and get it wrong… If I wait to act until I am the ‘perfect’ advocate, I will be dead and will have done nothing to help.”

Many people have already reported seeing people wearing safety pins, and feeling a sense of comfort, of unity, knowing that they are not alone in opposing the blatant racism and hate. Ragen Chastain, an advocate for the Healthy at Any Size Movement, wrote in her blog Dances with Fat, “I think that the safety pins serve to disrupt the assumption that bigots tend to have, that people like them hold the same prejudices they do.”

A number of articles have been published with ideas for further activism, how to make the safety pin really stand for something. In her first post about the safety pin initiative, Isobel Debrujah wrote about the importance of having a plan of action. She outlines questions for the person considering wearing a pin, such as, what are you willing to risk? Maeril, a French artist, created the following guide for deescalating harassment.

This article from Quartz talks about the ways people are starting to turn the safety pin initiative into concrete actions, including the creation of a network to connect people in Harlem so that people could have company when they felt unsafe walking alone.

Ultimately, the safety pin is a meaningless gesture if it is not followed up by direct action. Donating to organizations that help marginalized people, such as the ACLU, Planned Parenthood, or Southern Poverty Law Center, volunteering, or even just shutting down bigoted jokes when the people around you make them, all go a long way to helping counter the systems of oppression in this country. But the gesture of solidarity by wearing the safety pin, countering the narrative that the majority espouses the hateful rhetoric that seems to be everywhere, is also a powerful message to send.