Sister Frances Ann Carr, 89 years old, died this week, leaving only two left in a religious community that once embraced more than 5,000 Americans in the mid-19th century. Sabbathday Lake, in Maine, was her home from the age of 10.

The Shakers first came to the United States in 1774, according to the New York Times, persecuted both in Europe and here. They are known for their furniture and for their music; they did not eschew technology as the Amish and Old Order Mennonites do, but they lived simply – and celibate. They grew by converting members and by taking in and caring for orphans and children (such as Carr) whose families could not care for them (the children would have the choice to stay or go when they became adults – Carr chose to stay).

From the New York Times:

She arrived at the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in New Gloucester, Me., in 1937 as a 10-year-old, and brought a measure of mischief to the regimented life there: She drew other girls into tiny rebellions, like snatching a pail of maple sugar candy from a workshop, and even spit in one of her caregivers’ teacups after being punished for passing notes with a friend.

Over the years, Carr became an “ambassador” for the faith, writing a book on Shaker cooking and a memoir, in 1985 and 1995.

Sister Frances, who might be seen strolling the grounds in a deep purple traditional dress or singing “Simple Gifts” at the Sunday meeting, was, with others, a driving force behind the revival of the village’s commercial herb garden and livestock farm, the educational outreach that has drawn thousands of visitors, and the formation of the Friends of the Shakers, a volunteer and fund-raising group that helps to sustain the village.

“There’s probably been no other Shaker in history that was such a good-will ambassador of the Shaker Church as Sister Frances,” said Michael Graham, the director of the museum and library there.

Carr is survived by nieces and nephews and by the two remaining Shakers in Sabbathday Lake, Brother Arnold Hadd, 60, and Sister June Carpenter, 78 (NPR).

Last August, NPR interviewed Brother Hadd and Chris Moore, a Maine musician who grew up visiting Sabbathday Lake and is trying to ensure that their music survives. Aaron Copland and hymnals of many faiths have made “Simple Gifts” familiar to to many – it is just one of 10,000 some songs created by the Shakers.

“Of all the gifts that we have had, the one that has remained constant since 1747 when we began to today is music,” Hadd says. “It tells our history. It tells our theology. It tells about our daily living.”

Shakers lived a communal lifestyle. Everyone was encouraged to write songs; singing united them in worship. In the past, their villages would arrange to sing the same song at the same time of day as a way to feel connected across geography. But some of them, like “Bright Angels Descend,” haven’t been sung in more than a century.

Even in the last few years, the Shaker community in Maine has continued to thrive in its own quiet way, even with only three remaining members. Down East magazine featured the tiny community in a 2014 story and photo essay.

Today, they lease some of their farmland and all of their apple orchards. They raise cows for sale and bring in professional shearers for the sheep. They keep bees and grow vegetables and herbs. With a museum, gift store, and research library to run, they employ four people full time and as many as 12 in the summer. They manage and train a stable of volunteers, many of them friends and family who come back year after year. (Brother Arnold’s sister, for instance, helped plant this year’s garden.) They respond to an ever-surging tide of queries — from students, researchers, and eminent museum directors — and their online presence presumably comes with the same tech headaches that bedevil the rest of us. Sunday services are open to all and attract as many as 50 worshippers during peak tourist season.

The story includes Sister Carr’s memories from her first years there:

“…I did love the kitchen,” she recalls, gesturing behind her, where we hear a clatter of pans. “I started out as a ‘sink girl,’ peeling potatoes and that sort of thing, then I started cooking later on.” Sister Frances eventually found serenity with the motherly Sister Mildred, who took the girl under her wing and trained her as a teacher. She learned to love and abide by Mother Ann’s motto: “Hands to work and hearts to God.”

When she came of age, she elected to stay. Because her siblings decided “to go to the world” — as most children eventually did, with the community’s blessing — Frances felt a measure of pity for the Shakers, who’d invested so much in the children remanded to their care. But she didn’t join out of pity. In Sister Mildred she saw someone who lived the Shaker life “more completely” than anyone she’d ever known, and her example readied Sister Frances to make a lifelong commitment. She signed the Shaker Covenant with little ceremony in the presence of her mentor.

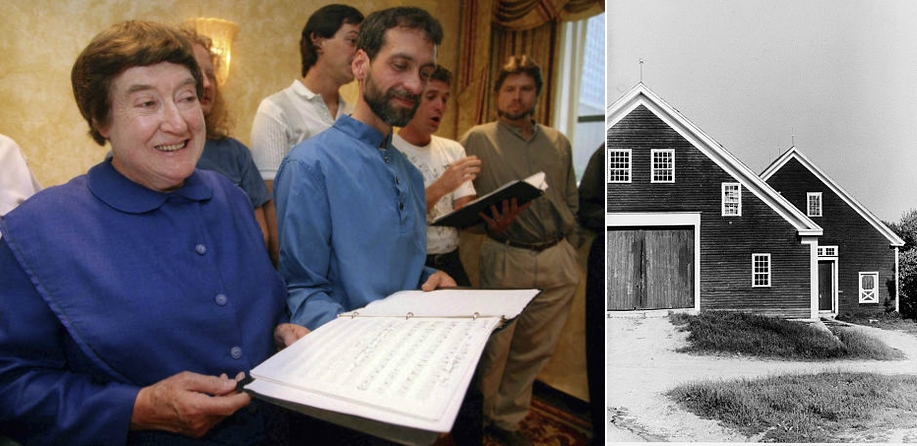

Photo, top left: Sister Carr and Brother Hadd; AP file photo.