by Tricia Gates Brown

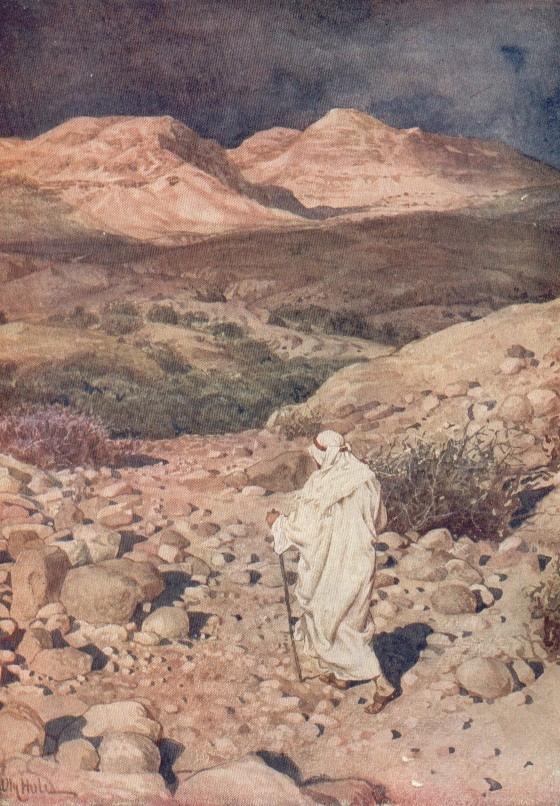

I occasionally see a massage-therapist/healer with strong intuitive gifts—a gentle but powerful person of faith with astounding insights. Once in early 2015, after I’d seen her a few months, she shared something she had “seen” in the course of an appointment. She was massaging my feet and in a straight-forward, unassuming voice, said, “I saw a person wandering in the desert wearing clothing that looked Middle-Eastern. It was Jesus wandering in the desert, but then it was you. It was as if you were at the end of a hard trial—similar to Jesus’ testing in the wilderness.” She said she didn’t know what this vision meant; she simply relayed it, sans interpretation. At the time, I was buoyed by the message. I reflected briefly on Jesus’ desert wandering and assumed the image referred to my chronic illness. I assumed it meant I was nearing the end, and took this as great news.

Then less than a month later, in February of 2015, a cataclysm rising as suddenly and unexpectedly as an 8-magnitude earthquake severed my five-year-old marriage, demolishing my image of shared life with the spouse I adored and depended on. In the wake of the cataclysm, I entered the most arduous period I have experienced—months of grieving, searching, spiritual trials, relational journeys, and mental and emotional reprogramming.

And somehow, my healer friend had seen it: the desert that awaited.

The forty-day season of Lent is traditionally viewed as commemorating Jesus’ forty days of wandering and being tested in the desert. It is a season of “preparation” through focused prayer, penance, repentance, almsgiving, atonement, and various forms of sacrifice. The entire liturgical year is a metaphorical walking out and remembrance of the Christian story and how it mirrors the human story, and within this metaphorical “walking out,” Lent reminds us that deserts are part of our journey. They are inevitable phases in the cycle of spiritual life, which is to say human life.

Since my 2015-16 desert experience, and the healer’s vision that presaged it, I have gained new perspective on why we do Lent. Never have I experienced such a charged and accelerated period of contemplation, growth, soul-searching, prayer, and turning (repentance), as during that time. And the fact is, we cannot sustain such periods. The intensity is overwhelming, and the level of focus needed to walk those times is too draining, drawing us away from other tasks. So every year, the liturgical calendar invites us to set aside forty days to be especially intentional about contemplation, growth, soul-searching, prayer, and turning. Surely, life will lead us into personal deserts that will accelerate our spiritual growth if we allow them. People we love will die or reject us; depressions and illnesses will come; jobs, homes, and other forms of security will be lost; we will become disillusioned about who we are and our purpose on this planet. We cannot avoid existential crises. But we don’t have to wait for the unexpected descent of tragedy and struggle to periodically intensify our spiritual practice and soul-searching. Tragedies will—hopefully—happen rarely.

To be honest, Lent meant little to me for most of my life. I grew up in a religious context where the Lenten ritual was not observed, and the giving up of certain habits in Lent seemed wacky to me, in my ignorance. I still tend not to “give up something for Lent.” But I appreciate more and more the liturgical season and the gift that it offers. This year I am trying to intensify and hone certain spiritual practices during the season, practices that will hopefully spill over into non-Lenten periods.

In my view, story is the greatest gift of the liturgical church tradition. Not only are stories read as part of weekly liturgy (one from Hebrew scripture; one from the gospels), but the weekly experience of liturgy—and the whole liturgical year—is an enactment of story. This seems to be God’s primary language—not only in the form of holy writings, but more notably in how the voice of God speaks through the quirky details of our very lives and through the evolving particularities of the universe. On a weekly basis, the regular rituals of liturgy/Eucharist walk us through the stages of the spiritual life and remind us of the life cycles, including the “desert,” present most notably in the confession, where we kneel and practice self-awareness and humility, training a loving searchlight on our ego-protection measures.

At the end of the liturgy, after we have metaphorically and ritually walked through and remembered the cycles of human life, we “go out into the world” from that place of remembrance and grace. In the church I attend, we end with my favorite words in the Book of Common Prayer: “Send us now into the world in peace, and grant us strength and courage to love and serve you with gladness and singleness of heart.”

These words point to the trajectory of the spiritual life and its liturgical reenactment. It is to direct us to a life of peace, love, service, joy, and “singleness of heart.” Every Sunday, as we end on these words, we are reminded of the why, of the purpose and meaning of our human, God-infused lives. It is also the why we strive for as we reenact Jesus’ forty days of desert wandering in Lent. Surely Jesus went out from the desert into the world in peace, love, and service.

More than ever perhaps in my lifetime as an American citizen, I see an acute need for peace, love, and service, for strength and courage. Our country seems soul-sick and hungry for these things. Therefore, Lent seems especially important this year. Imagine if a significant number of Americans set aside forty days to more intensely and intentionally focus on contemplation, growth, soul-searching, prayer, and turning—all for the purpose of peace, love, joy, and service. Imagine the preparation this would bring. Preparation for greater unity, compassion, and forgiveness, but also for standing up for love and inclusion, and for speaking the truth.

Tricia Gates Brown works as a writer, garden designer, and emotional wellness coach in Nehalem, Oregon. She holds a PhD from the University of St. Andrews. In 2015 she completed her first novel and the essay collection Season of Wonder, and is currently at work on her second novel. For more, see: triciagatesbrown.net

Image: By William Hole [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons