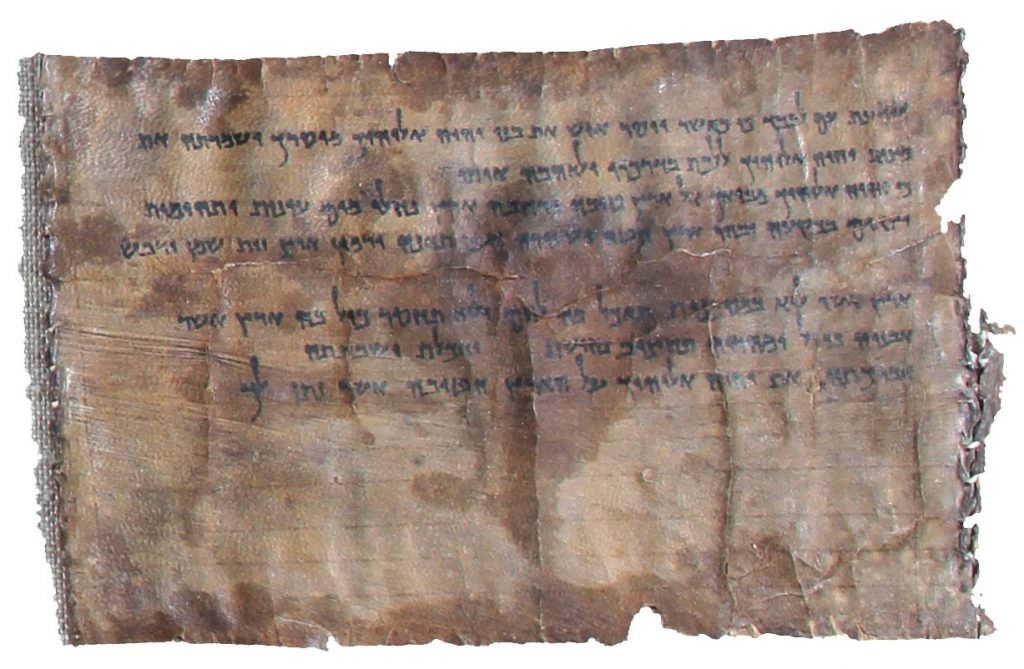

Deuteronomy 11:18-21: Fix these words of mine in your hearts and minds; tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Teach them to your children, talking about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Write them on the doorframes of your houses and on your gates, so that your days and the days of your children may be many in the land the Lord swore to give your ancestors, as many as the days that the heavens are above the earth.

We all have life-shaping mega-stories—or traditions—that have shaped us since childhood. And most often we don’t “fix them to our hearts and bind them to our foreheads.” Instead, they operate outside of conscious awareness. In my own life, powerful evidence of a mega-story first emerged when I was in middle school. It began in seventh grade when I was bullied by two boys who took issue with my shoes, which my frugal mother always bought at Payless. This was 1982, around the time name-brands like Nike and Adidas gained dominance in the adolescent psyche, and these boys would follow after me, hissing out the phrase “cheap kind, cheap kind!” lengthening the letters of the second word like: kiiinnnddd. As a highly sensitive, shy kid who strove to please, I was troubled by these boys unto near-suicidal despair. Then the next year, while in eighth grade, I got on the wrong side of the “popular” girls in my class when I declined to drink alcohol at the tender age of thirteen and bowed out of their company. Their bullying taunts involved sniggering about me from the back of the classroom, calling me stuck up, and in one instance, penning the word “BITCH” across my locker in broad letters with indelible marker for all and sundry to see on their way to gym class. They TP-ed my house with so much toilet paper it was like they’d high-jacked a Costco supply truck fresh from the toilet-paper factory.

The months of seventh- to eighth-grade seemed endless. I became depressed and dreaded school daily. But a couple of months before eighth-grade graduation something started to shift. At some unknowable point, I figured I needed to try living a “story” I had picked up in my life about loving your enemies. Not consciously—mind you. I honestly don’t remember being told stories about loving one’s enemies, and certainly didn’t realize I had been influenced by a mega-narrative, or tradition, in my decision to try loving my enemies. It was just something I knew, something I had absorbed by osmosis growing up in church, where I had presumably heard it referenced on occasion. My parents were definitely not peace activists. In fact, my dad was and still is a fairly hawkish conservative. Yet in his personal life he did things like lend his newly restored-by-hand bicycle to a troubled young man who needed it—and who never brought it back. Dad wasn’t bitter toward the young man as far as I could tell. He forgave him. And perhaps I understood that “loving your enemies” was just what one did as a Christian; that heaping kindness on our enemies was the best revenge, akin to “heaping coals on their heads,” in the hyperbole of Jesus. In any case, in eighth grade it dawned on me that I should give it a try.

I started looking directly into the eyes of the girls who disliked me, and smiling at them. I would go out of my way to tell them hello. When I liked something they wore, I complimented them. I stopped dissing them behind their backs. Rather quickly, their attitudes toward me started to change and the bullying stopped. Relief buoyed me up and over the line of eighth-grade graduation, as finally the tortures of middle school were over. And though I had started the experiment as a mostly unconscious strategy, with little genuine regard for the girls, I found that over several weeks as I acted friendly toward them, my feelings started to thaw. I didn’t want to join their crowd, mind you; I didn’t suddenly trust them. Surely, I didn’t love them in a soul sense. But no longer did they feel like enemies. In almost every case, the girls seemed to forget their disdain for me.1

What my adolescent experiment evidences to me—looking back from the distance of thirty-plus years, is that some mega-narrative had had its way with me from a young age, and I wasn’t even sure where it came from. The story worked on me in a subconscious way, below awareness. Yet work on me it did.

The Deuteronomy scripture that is part of today’s lectionary commends the conscious adoption of one’s tradition or mega-story: “Fix these words of mine in your hearts and minds; tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Teach them to your children…” More and more, I am inspired to ponder this idea. Because our culture seems to be anemic when it comes to consciously adopted tradition, and it doesn’t seem to be serving us well. In the vacuum created, we don’t become non-traditional (again, we all have traditions), but we come to be lead around by traditions that are unexamined and, sometimes, toxic.

Yes, I realize tradition is about as popular as aspic—those savory molded gelatins popular in the 1950s along with the Masonic Temple and Rainbow Girls. As a collective, Americans have spent decades breaking free of religious norms, and socio-political ideologies like communism and fascism. The growing rise in religious fundamentalisms and nationalism seen on the far right is a reaction to a general societal trend toward non-affiliation with consciously-chosen traditions.

But we still operate under mega-stories telling us what it means to live a good life. These mega-stories can center around sports culture, material prosperity, or raising successful children. Still, they are unifying narratives. They are traditions. But again, few are consciously aware of their traditions.

I wonder if—as suggested by the Deuteronomy text—choosing a tradition consciously is helpful. I believe it sets us free to scrutinize our tradition and debate with those within it, deciding what aspects of the tradition we care to reflect in our lives. Consciously chosen traditions can serve as counter narratives as we encounter destructive mega-narratives bolstered by dominating powers all around us. In this sense, consciously chosen traditions do set us free. Without awareness of the traditions dictating our values, we can adopt unhealthy traditions that lead us around by an invisible leash. Rarely do we stop to scrutinize why we flock en masse to see the latest Marvel-figure action movie or cheer for the fighter planes doing fly-by’s at small-town parades, why we fan-atically follow sports seasons and favorite teams, why we buy so many Christmas presents for our children. In each case, we operate as adherents to dominant traditions—we just don’t identify as adherents. We don’t understand the sway the tradition’s “unifying narrative” has over our lives, let alone its global impact. There is nothing inherently wrong with watching superhero films or sports or buying Christmas presents, per se. But are there problems with the unconscious ways we engage in these activities, not realizing how they have formed our tradition and become our guiding narratives?

[Public-domain image information: The first of two parchment sheets making up 4Q41 or 4QDeuteronomyn, also known as the “All Souls Deuteronomy”, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated to the first century BC. This first sheet contains Deuteronomy 8:5-10.]

[1] Note, I do realize the stakes were incredibly low in my adolescent experiment in nonviolence, and I’m not suggesting one can “simply” use kindness to reverse the intransigent hatred of, say, autocratic authorities, white supremacists, cruel prison guards, or the like. Relatively speaking, “loving my enemies” was easy in my case because my enemies were of the Care Bear variety.