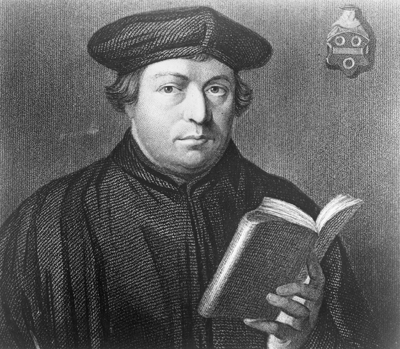

Today, February 18, is the feast memorializing Martin Luther. His importance to the Reformation cannot be questioned. I will readily grant that without him, another would have emerged, as many had before him. Wycliffe, Jan Hus, to name but two. But also Wat Tyler led the peasants revolt in 1381. While often attributed to economic reasons, it was formed and fueled by John Ball’s radicalizing sermons. Change was in the air, and the Church in the West had become too centralized, too powerful, and far too greedy. And here comes Brother Martin, a priest and monk (regular canon) of an Augustinian order in Erfort, bright, articulate, and hungry for God’s grace. The fear of damnation, and its subsequent solution by selling indulgences, which may or may not have impressed God, but surely increased the Church coffers, is not an unfamiliar theme in documents from this time.

Martin had had a strict peasant/middle class upbringing, and his father wished him to study law. At his Latin school he studied and prayed with a group following the way of the Brethren of the Common Life, a lay, un-vowed, devout movement of women (Beguines) and men (Beghards) who lived in community and practiced Devotio Moderna, a non-dogmatic piety whose importance to the foundation of Protestant Reform (and through Erasmus, Catholic Reform) cannot be underestimated. Luther began university, but after a close and terrifying lightning strike he vowed himself to God and entered the Black Cloister monastery. He is quoted as having said of this time, “I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul.” Although spiritually advised that a change of heart would cure his lack of faith and melancholia, this fear drove him to seek his own understanding, partly through philosophy, especially Aristotelian logic, but finally in Scripture, through which he became convinced that by God alone would we receive grace and salvation.

Why Luther succeeded where others failed had a lot to do with politics. His famous 95 Theses, believed to have been tacked onto the university community’s bulletin board (a door), was merely an invitation for a lively debate with peers. But given everything, it spiraled into a Church scandal, and either the now Rev. Dr. Martin would recant or there would be a reckoning. He didn’t. But more than one of the German Electors (in effect, princes) were delighted to have a theological way to be quits of Rome and supported him through years of trials and concealment. How being excommunicated and declared an outlaw must have tested Luther, who only wanted to reform and not split the church, is only for God to know. But he stood fast.

Always the teacher, he wrote catechisms and books at a prodigious rate, trying to spread the Gospel through knowledge and understanding, but primarily through knowing Christ from the Gospels. His translation of Scripture into German, and beautiful German, may I add, was groundbreaking in that now the common person could read and meditate on the actual words. And they inspired Tyndale to translate the Bible into English, for which every Anglican can give thanks, even if we have moved to less poetic but more accurate translations. Luther’s marriage to Katharina von Bora set the model for clerical marriage, and, in their partnership, for Christian marriage. Luther wrote many wonderful hymns and encouraged them to be sung by congregations of ordinary people, a practice which endures. And he never stopped writing and preaching.

So now we have had a quick look at Luther. But there is another side, one that today we would consider a dark side. One that in today’s political atmosphere would have had him driven from the public stage and the Church. He only partly supported the Peasant War (1521-25), but successfully encouraged the radical reformers to return to their homes. He supported the ruling authority, not the poor and needy. He did save lives and restore order, and the radical arm of the Reformation grew in other places, but he was hardly the icon of radical social justice. Most egregious by today’s lights, he was a vehement anti-Semite. Although efforts are made to excuse his increasing anger toward Jews to his terminal illness, that attitude was part of the common parlance of his time and place. What would a 24 hour news cycle and social media have done to him today?

In the readings for the feast, Isaiah (55:6-11) sums up Luther’s obedience to what he received from the Holy Spirit. Seek the Lord while he is near. Let the wicked repent their ways. God’s thoughts are not our thoughts. God’s words will not come back to him empty. As indeed they did not. And Psalm 46, “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore we will not fear,” (Ps 46:1-2a). Next time we pray the Confession in our private prayers, consider how much fear Martin Luther must have wrestled with, how much he had to cast off, turning to God for consolation and for assurance that he had not sinned, was not a heretic, but was doing Jesus’ will. And finally John 15: 1-11, the Parable of the Vine, not only can this be read as post-Reformation denominational branches with Jesus at the center, but each of us are a branch of that vine. And the Father prunes whom he loves. As Luther was pruned. As we are pruned. As our Church is pruned to yield more fruit. Abide in Jesus. Keep his commandments.

We are still facing change. Resolution B012 which was passed into Canon Law in 2018 on same sex liturgical marriage has moved the Episcopal Church towards embracing all of human sexuality and relationships, yet it still separates us from those who either can’t or won’t embrace this new revelation. And many can’t forgive those who disagree with us. And what about those who have sinned once long ago and yet have amended their lives and done much good? I see unwillingness for reconciliation in statements like “Kill the patriarchs.” I know many fine strong men who add to our Body in Christ, as I see more and more strong women take their place at the table, both holy and secular. And I would rather see a man turn to the recognition of equality of the genders than castigate all men guilty of past mistakes, and certainly not blame all men or all white people or all anybody for perceived sins. Because we all matter to God. We are all sinners, and as much victims as perpetrators in our time and place.

Jesus taught us to show mercy and forgive our enemies, spiritual and political, as well as those who confessed and repented. We are to flood them with “the fruit of the Spirit [which] is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control,” (Gal 5: 21-23a). I forgive Martin Luther for his failures, and I thank God for him and his courage, and his wisdom which brought so much to the Reformation. I implore that we sinners consider reaching out to those who have stumbled, that we forgive in Christ’s love and mercy. In this political climate we need to be Christ’s Body in the world and bring the Gospel into the Light where all may see, as did Martin Luther, priest, reformer, theologian, and teacher.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is a parishioner at All Souls Parish, Episcopal, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California