R is the number of times an infected person transmits the virus to others, on average. Writing in the Atlantic, Zeynep Tufecki argues that R, for this virus, is not the key to its control. Rather, the key is k, the dispersion. This virus spreads in clusters whereby a few contagious individuals are responsible for most of the transmission. Concentrate on eliminating cluster cases and the virus becomes easier to contain.

The upshot for churches: we shouldn’t be returning to normal any time soon.

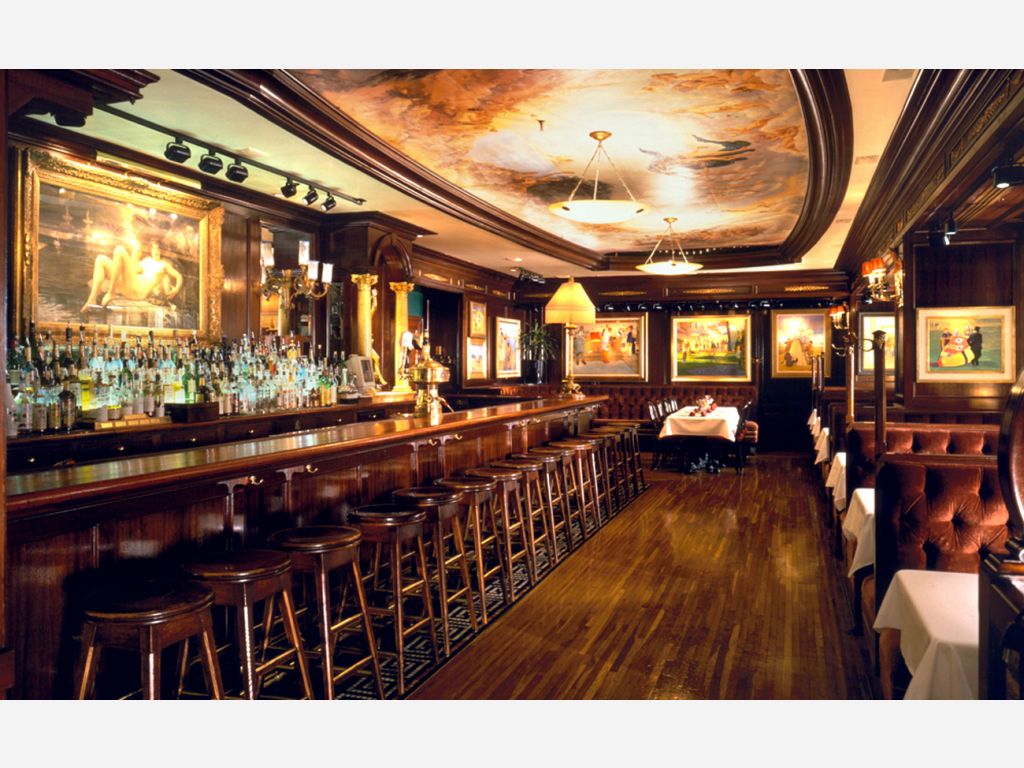

In study after study, we see that super-spreading clusters of COVID-19 almost overwhelmingly occur in poorly ventilated, indoor environments where many people congregate over time—weddings, churches, choirs, gyms, funerals, restaurants, and such—especially when there is loud talking or singing without masks.

…

As Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at the University of Florida, told me, given the huge numbers associated with these clusters, targeting them would be very effective in getting our transmission numbers down.

Overdispersion should also inform our contact-tracing efforts. In fact, we may need to turn them upside down. Right now, many states and nations engage in what is called forward or prospective contact tracing. Once an infected person is identified, we try to find out with whom they interacted afterward so that we can warn, test, isolate, and quarantine these potential exposures. But that’s not the only way to trace contacts. And, because of overdispersion, it’s not necessarily where the most bang for the buck lies. Instead, in many cases, we should try to work backwards to see who first infected the subject.

What do bars, dance clubs, funerals, weddings, church, choir practice, meat packing plants have in common? What can we learn from this?

Dispersion may be frustrating but it is good news. We can use a scalpel instead of bludgeon and limit collateral damage. https://t.co/c2eTFF3jSO

— Amy Cho, MD MBA (@amychomd) October 1, 2020