If we can’t identify the source of a problem, we’ll never find the solution. One of the funniest examples of this was a skit I remember seeing on television years ago. A couple gets in their car to go for a drive. The key is put into the ignition, the key is turned, and the engine won’t start. The man gets out of the car, opens the hood, immediately starts, wiggling a few cables, and asks his wife, “Try it now.” She does. The car won’t start. Next, he has her pump the gas pedal a few times. “Try it now.” Nothing. Next, he kicks the tires, opens and closes the trunk, and says, “Try it now.” No go. After a few more attempts to find the problem, his patience wearing thin and out of ideas, he washes the entire car and asks his wife, still sitting in the driver’s seat through all this, to “Try it now.” In the final scene, the man is frustrated and furious, covered in sweat, and the whole car has been freshly painted red. “Try it now!” Of course, they remain in the driveway.

This is a good metaphor for how we sometimes think of addiction and recovery. If we don’t correctly identify the source of the problem, there won’t be a sustainable solution. But aren’t the sources of these problems obvious? At first glance, it would seem that the problem of the alcoholic is alcohol; that the problem of the gambler, gambling; that the problem of the manipulator, the need to control. It would be great if life were that simple. But if that were the case, the alcoholic, for example, would try alcohol a few times, realize it’s not for him or her, and put it down. The overeater would get sick after two gallons of ice cream and put down the spoon. The manipulator would realize that his or her actions cause rifts and resentments, and quit those tactics.

Yet we don’t. Whether our addiction involves a substance or a behavior or a pattern of thinking, we keep on returning to the addiction, time after time, baffled at ourselves. And if all we do—through a great feat of white-knuckling willpower—is put down the bottle, the pills, the ice cream or the dice, what we find is we feel worse, not better. If we know someone in that situation, what’s called a “dry drunk,” we might find ourselves thinking, “I wish s/he would go back to drinking (or smoking or whatever)!” They’ve painted the car red, and the paint begins to peel and things are worse than before.

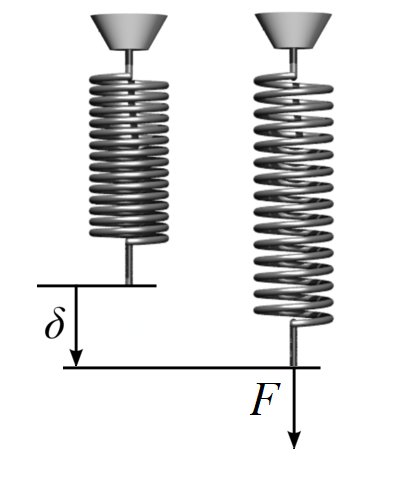

This is because the problem of the alcoholic is not alcohol; it’s alcoholism. Alcohol (or ice cream or dice or sex or banging on the steering wheel) is not the problem… in fact, it’s a solution, a way of medicating the problem. The problem is what Bob D. calls “the coiled spring.” Bob, a national-level speaker within the recovery community, says that inside every alcoholic/addict there is a spring in the gut that gets wound tighter and tighter. Each resentment, each emotional wound, each baffling situation, increases the tension on the spring. Our fear and anxiety continue to grow, and we suffer. At some point, our suffering is great enough that we need relief. The alcoholic or addict finds (temporary) relief/escape through their addictive behaviors.

Our addictive behaviors, however, themselves increase the tension on the spring, and one spirals down and down as the spring becomes more and more compressed. What we need to do, says Bob D., is engage the source of our problem—the coiled spring. This coiled spring is the –ism, and it’s not caused by the people, places and events in my life, but from my responses and reactions to the people, places and events in my life. Like that scary moment in a horror movie when the potential victim realizes the calls are coming from inside the house (!), I come to realize I’m the one putting the tension on the spring.

Recovery, some say, is about learning that we have more options than we thought we once did. When we feel a slight compression in our coiled spring, we do not need to escape into the tried and true—but destructive and false—patterns of addictive behavior. We can learn new ways to manage that tension. Putting down the alcohol, or cigarettes, or self-pity or passive-aggression is a requisite step in beginning to treat the –ism, the root of the disease of addiction that manifests in so many destructive forms. “The great person dwells on what is real, not what is on the surface; on the fruit, and not the flower,” as the Chinese classic Tao Te Ching reminds us.

Jesus, too, seems to have understood that much of what we do, say, and think is driven by ingrained patterns of responding to the stress and tension of the spring in our guts. Who we are in God—the image and likeness of God that we all share—is often hard to see behind. How else would it have made sense to him to spend time with “sinners” such as tax collectors, prostitutes, and the ritually impure? Surely he could see their –isms at work, and could see beyond the –ism into the depth of the true person. While some only saw in Matthew “tax collector” (perhaps Matthew’s –ism was greed or power?) Jesus saw “disciple.” Some only saw in Bartimeus “blindness” but Jesus saw “a follower of the Way.”

Who are we behind and beyond our compulsive reactions to the fear and anxiety in our lives symbolized by the spring? The answer to that question comes, for those in recovery, through working the Twelve Steps. For all of us, learning to give some slack to the coiled spring in our guts can help us uncover the state of natural centeredness and relaxedness that recovery spirituality calls “serenity.”

We will treat the Twelve Steps in depth later in this series, but as a preface now we can consider how time and space operate on our inner spring. When life is hectic and overscheduled and frantic, our springs become tighter. When we allow for free space, for times of relaxation and play, we loosen up. There was an interesting study done among seminary students in which students were split into three groups. Each group was told they had to give an impromptu talk on Jesus’ parable of The Good Samaritan. Two of the groups were told they had to rush across campus, as the group members needed to give their talks as soon as possible. The third group was told they had to give their talks in an hour, meaning they could take their time crossing the campus. The researchers placed an actor in the path these students would take, someone who pretended to have severely twisted their ankle (mimicking in a way the Good Samaritan story itself!). Of the first two groups, very few seminarians stopped to engage the actor; almost all the students of the third group did.

The first two groups were rushed; their springs were compressed. Their –ism (I, Self, Me) was activated; they passed the hurt man, intent on accomplishing their self-will. The third group had the open time, the psychic space, to respond in a deeper, more engaging way with the actor. Were these seminarians in the third group more holy than those of the other two groups? It’s unlikely. The difference? Open time, a less compressed spring.

So the next time you feel the first inklings of fear or anxiety begin to tighten in your gut, perhaps create a moment of open space, and see if a new option presents itself outside of your usual patterns (especially if your usual patterns tend to make you suffer in the long run!). And the next time the car won’t start, take a breath before running for that can of red paint.

Image: “Stiffness of a Coil Spring,” AndrewDressel / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

James Reho is an Episcopal priest, school chaplain, and spiritual director. He is also a devoted husband, part-time gardener, and aspiring fiddle sensation. 12-step spirituality holds a central place in his life, which he tries to live one day at a time.