Happiness can only be achieved by looking inward and learning to enjoy

whatever life has, and this requires transforming greed into gratitude.

– St. John Crysostom

One exercise I practice when I work with children is to have them go through the facts and events of their morning routine. These facts and events typically look something like this: Waking up, getting dressed, eating breakfast, brushing teeth, combing hair, packing books, and being driven to school. After going through these facts about the morning, I point out to them that we always also create a story about the facts. The facts are what they are… what makes them interesting is the story we attach to them.

Exploring the possibilities of story around these facts, we next craft two caricatured story-makers. Story-maker one says about the morning, “Geez, why do I have to wake up at 6:30? I’m so tired! This is terrible. I wish I had new clothes! This stuff I have to wear is out of style, not cool and not as nice as so-and-so’s clothes. Oatmeal again! What is this, a gulag? Why can’t anyone make me a decent breakfast that I’d actually enjoy? My toothpaste tastes like $%^&*. That one I saw on TV looked like it would taste awesome. Why can’t I have that one? And now I’m being rushed to school, carrying all these heavy books, and all day long I’m going to have to sit in a crummy desk and do what I’m told. What could be worse?”

Story-maker two takes a different tack: “Wow, I got to sleep in a nice and safe bed last night! And here I am, awake and alive and healthy, living with people who love me and treat me with respect and kindness (at least most of the time!). I have clean clothes to wear, and I’ve seen pictures of kids who don’t… that must be awful. And I’m thankful for food that’s made for me and is good for me, and thankful that I can brush my teeth easily from the tap, instead of having to carry water from far away—I’ve seen pictures of kids who have to do that, too. And instead of doing some hard labor for my family, I get to be driven to school, where my “job” is to be curious, learn, and have some fun with my friends when the teacher isn’t looking. What a great day!”

The interesting thing, of course, is that in this thought experiment both story-maker one and story-maker two have had the exact same morning according to the facts. What makes their mornings so different are the stories they attach to the facts.

What kind of story-maker are you? If you’re like me, you probably have pieces of both story lines rattling around in your head and heart through the course of a day. Sometimes we feel resentful and entitled, sometimes thankful and full of gratitude.

With Thanksgiving around the corner, I’ve begun to notice what I notice every Thanksgiving: lots of conversations around who’s going where, laments around the cost of gifts and big meals, and monologues about what folks are looking forward to… in other words, about what they want, either in terms of goods or experiences. What I don’t tend to hear as often are the pieces of story-maker two: gratitude and thanksgivings. This is sad. It’s sad not because we “should” feel thankful, as if it’s a stern heavenly imperative… I tend to think people ought not to “should” all over themselves as much as they do! Rather, it’s sad because when we leave the practice of gratitude to the New-Agers (or to those we’ve determined should be grateful to or for us, lol), we miss out on the richness and joy of life. We have mornings like story-maker one, and miss out on the life of story-maker two.

One can argue that gratitude is a central pillar of recovery spiritualty. As early as 1949 Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, advocated that Thanksgiving week should hold a special place in AA culture. In Twelve Steps an Twelve Traditions, he lists “a genuine gratitude for blessings received” as one of “the permanent assets we shall seek.” (p. 95)

Even stronger than the many sentences extolling gratitude in recovery literature are the many warnings against resentment. In Alcoholcs Anonymous (The “Big Book”), Bill writes, “Resentment is the number one offender. It destroys more alcoholics than anything else. From it stem all forms of spiritual disease…” (p. 64). Resentment and gratitude cannot cohabitate; they are mutually exclusive.

One way, then, to edge out the space resentment seeks to claim in our hearts and in our lives is to cultivate gratitude. Recovery spirituality is clear that we do not have the power to remove our own shortcomings or malformed patterns of thinking (like resentfulness)—only our Higher Power can do that. However, what we can do is to cultivate virtues that edge out our shortcomings. So if I want to avoid the poison of resentment in my life, I can cultivate gratitude. I can edge out story-maker one, and give more and more of the microphone time to story-maker two.

However, the practice of gratitude—what many New Age teachers call the “attitude of gratitude”—has been so popularized since the first days of the Big Book that it’s become, in some circles, associated with a surface-level, Pollyanna type of spirituality that avoids the hard facts and sets us up on a pink cloud. The attitude of gratitude often presents as nothing more than a platitude.

Yet recovery spirituality—as well deep strands in Christian spirituality and other spiritual traditions—highlight gratitude and thanksgiving as an integral part of spiritual maturity. St. Paul links giving thanks to joy in life: “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances, for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.” (1 Thess 5:16-18). In that masterwork of Christian spiritualty, The Philokalia, St. Anthony the Great states that the “truly wise person” is marked by gratitude: “Whatever he may encounter in the course of his life, he gives thanks to God for the compass and depth of His providential ordering of all things.” Even the Eucharist, the traditional (and most correct) name for the service of Holy Communion (“Mass”), comes directly from the Greek verb eucharistein (“to give thanks”)!

So… how do we do this? It’s easy enough to make the case for gratitude/thanksgiving to be a strong part of our spiritual maturity, but simply wishing to be a grateful person isn’t quite enough, otherwise we’d all be so, all the time. And you’ve likely had the same frustrating experience I’ve had: hearing preachers or spiritual teachers tell you that you should be grateful, should give thanks for all things, but offer nothing in terms of how. Recovery spiritualty, always practical, tells us that we need to take strong action here. Through working the 12 Steps, we come to be grateful persons, who no longer (or better, not as often) fall prey to resentment or entitlement or frustration when our egos don’t get exactly what they want.

In the coming year, we’ll be looking deeply into the 12 Steps, but for now here are some tools that can be powerful aids in cultivating gratitude and living more into the reality of story-maker two:

- Remind yourself, “I don’t know what’s good for me.” How often do we label something that happens as “good” or “bad” to find out that, in the long run, the opposite was true? These labels of “good” or “bad” are typically how our egos categorize the people, places, and things (and events) that make up our lives. By “good” or “bad” what we really mean—think about this and I think you’ll agree—is “pleasing” or “not-pleasing” in terms of my ego’s desires. And my ego isn’t very bright; it is mostly driven by instinct, and malformed instinct at that. So the next time something “good” or “bad” happens, we can try to remember that, since I don’t know what’s good for me, I need to reserve this kind of judgment for a later time. I need to speak my story differently and avoid unexamined categories.

- Remember to say, “Thank you.” Whatever happens in life, practice making “Thank you” your first response. Won the lottery? “Thank you!” Lost a job? “Thank you!” Stubbed your toe on the toy you’ve asked your child to put away fifteen times? “Thank you!” Now, you may not mean this the first time something happens that would fit into the “not-pleasing” category… but say it anyway—and then try to see how it may be true. Lost that job? Perhaps I needed that nudge to explore what I really want to do. Stubbed that toe? What a great way to work on patience and explore the roots of my tendency toward anger. There is always a way we can say “Thank you” and make that part of my story. And yes, this is hard to do.

- Write it down. Keep a jar in your kitchen or on your desk, and make it a regular practice to write down something you’re grateful for on a post-it and add it to that jar. When it’s full, take some time and read through them all. Or each morning, write down three things you’re grateful for (different than the day before) in a journal. At the end of the month, read through your journal. Writing something down makes it real, anchors it in time, and allows us to go back and see how the story unfolds. This one isn’t too hard to do.

Using these techniques, which follow the spirit of recovery work, can help all of us access the power of thankfulness and gratitude in our lives… and therefore increase our joy and enhance our experience of being alive. And wouldn’t this week, Thanksgiving week, be a great time to start?

When I do my morning routine thought experiment with children, I end by asking them which story-maker they think will have a happier day. They all respond, “Number two!” and they are right. What I leave unspoken, but comes across very clearly, is that the cluster of facts don’t have to change at all… all that changes is us, and that changes everything.

Happy Thanksgiving, friends… may your holiday truly be a time of giving thanks!

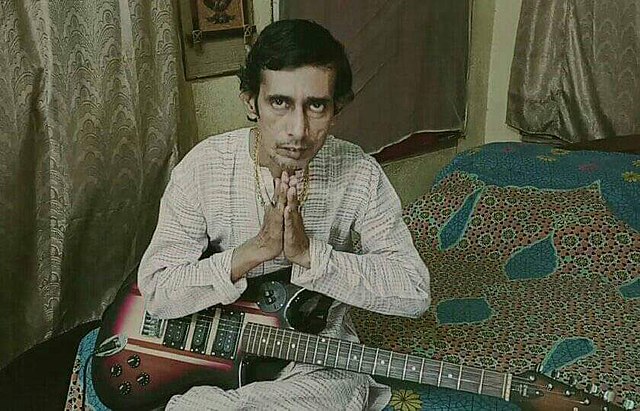

Image: Pandit Soumendu Lahiri, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

James Reho is an Episcopal priest, school chaplain, and spiritual director. He is also a devoted husband, part-time gardener, and aspiring fiddle sensation. 12-step spirituality holds a central place in his life, which he tries to live one day at a time.