In the darkness of the Dark Ages (about 500 CE to about 800 CE), God was presented to the people by the bishops and clergy of the church as a fearful, veiled mystery. God was off in the distant darkness, angry, brooding and vengeful. The imagery was presented as more like a vicious teenager than a loving creator. These images made the people afraid. And when people are afraid, they will do anything. In the Dark Ages what they did to hold this God at bay was to pay their tithes and sin less. Or perhaps get caught sinning less.

Not much changed in the Middle Ages (about 800 CE to 1500 CE) except that the system the church put in place dominated. So much wealth was gained that this system seemed more charmed than blessing. Thinking themselves some sort of royalty, Clergy and Bishops wore silks and jewels while the peasants starved and worked themselves, literally, to death to pay land rents to the monastery and the other landed class. But still, to people who lived in windowless huts of mud and stick with beef tallow for stinky, smoky light and nightly rations of weak stew, that darkness was frightening.

Then, one thing changed the world.

In Italy, in the 14th century, the second Black Plague arrived from the Crimea on a ship, on fleas, on black rats. This plague followed the great famines of the previous century. and killed as many as 60% of Europeans. So, in a family of 10, six would be dead. Look at a family photo on your wall and think about that for a moment.

Having no imagination on how to respond, the church doubled down: famine and the plague were used to further frighten the people. More tithes meant more wealth and the church became even more rich. By telling people that everything that happened was the result of God’s blessing or anger, the people were simultaneously convinced that whatever they could do to please this angry God who spoke through the voice and actions of the clergy the better. For a people who were taught that if a mother prayed while boiling an egg, God would tell her when it was done, what they were told seemed the only option.

The Black Plague of the 14th century left a mark on the world forever, affecting everyone. Illness infected the people, but bishop and priest, too.

This was noticed and a light began to dawn in the minds of the people, “Is all this fear about God’s vengeance true?”

The Black Plague brought upheavals to the religious, social, and economic systems. The Dark and Middle Ages were no more. The Renaissance began. Art gave previously flat images of spirituality a dimension for the first time. And it was in this era that people found the courage to begin to push back against the church and its damaging dogmas. The church’s counter-punch was strong. Heretics and questioners such as Joan of Arc were burned at the stake. Others fared worse, if possible, in the Inquisition and other trials. Holding fast to what it knew, the church began to lose its grounding in fear as science and freedom-of-thought and Gutenberg’s presses began to grind out superstition.

Now, we are in another such time of transition. And the effect on the church is pronounced. Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, Generations X, Y and Z have been quietly leaving the church. By 2000 and, for the first time in the 2000 years of the Church, three generations in a row were staying home to their grandparent’s annoyance and the tithe dependent church’s confusion.

From that point, like global warming, it has just been a matter of math of what comes next.

From that point, like global warming, it has just been a matter of math of what comes next.

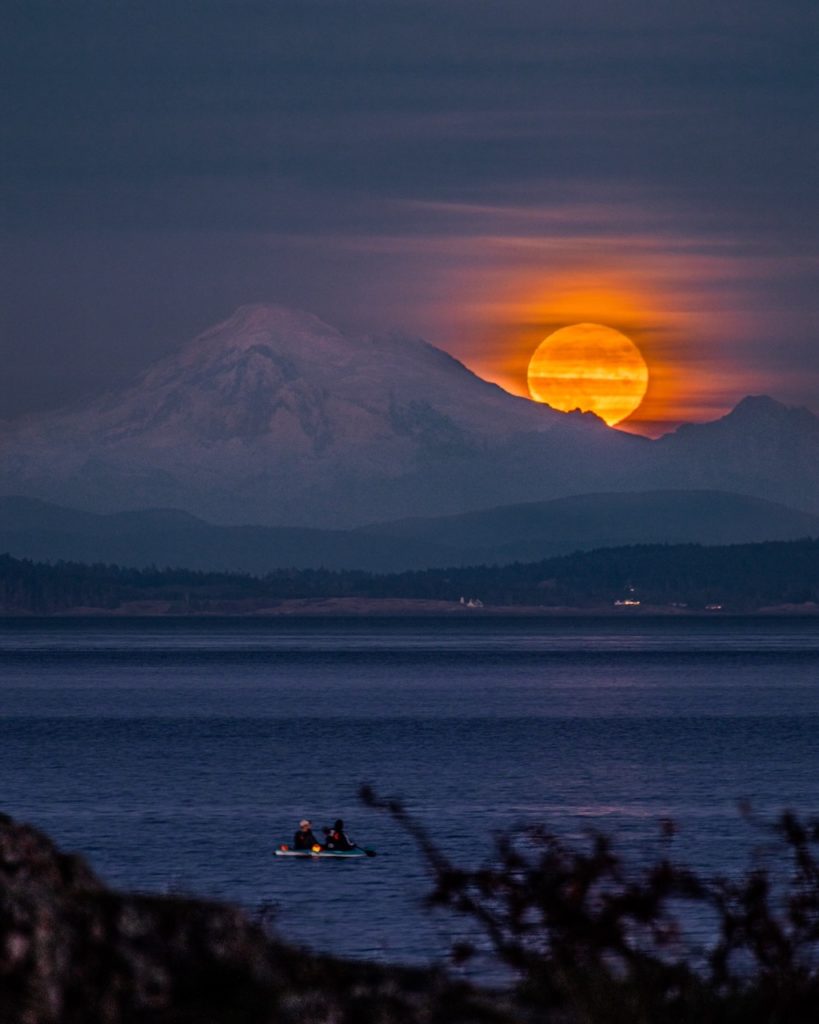

This image was taken on Whidbey Island, where I live. My friend, Neil Dickie, captured the setting sun as the last few kayakers were ending their day of exploring the Salish Sea British Columbia.

For the most part, we no longer huddle in fear as the sun sets, worried about angels and demons – except those which live within us. Prayers to God for help in boiling eggs are long forgotten. Bowing or crossing ourselves when we pass a member of the clergy now seems quaint. And it’s longer fear of God’s wrath if we don’t give to fund heating massive, empty buildings six days a week. Or the clergy and bishops that tend and are tied to those buildings.

The Renaissance was a time of tremendous creativity and liberation. People invented and tried new ways for everything: to treat diseases, new ways to live without fear and yet, still made ways to be together in new groups. With and without the church, the Renaissance changed the world; it took a plague and lots of death to birth that change.

We do not know what this 21st century plague will bring, long-term. We do not know how it will affect the church and its communicants. We do not know how new spiritual practices will be inspired. But they will appear, in the comfort of our own homes, forests and beaches. With this possibility, it’s unknown if enough people will go back to attending and paying for the church model with which we all grew up and struggled. However, after three world-wide plagues and three consequential “ages” we are soon to find out.

As for me, I am going DIY with my spirituality. I am seeking community among potters and friends. I am buying books to figure out God on my own, asking no permission from the edifice of bishops and clergy. I am seeking “spiritual cleanliness” no longer from sacraments from the hands of priests on behalf of an angry God. Rather I am inspired finding my own rituals, self-created on behalf of a hilarious, beautiful God who loves and creates with such ferocity. This God has little time for discipline-by-illness or canon.

God did not send the pandemic, but God wades into it with us. And like parents watching their children succeed and fail, winces at our pain and delights in our new creations.

I have a vision of an age in which we no longer retain and depend on people to show up at our bedside in hospital with water, wine, bread, oils and crosses. I have a vision in which we self-organize and do that ourselves for each other. It is a vision in which nobody preaches at me, but rather, God invites me to interpret for myself. It is a vision of dogma-free Sunday mornings in pajamas with friends and family making pancakes and laughing or in hiking boots on a beach.

It is a new day. It is a new era. It is a new political administration. It is a new vaccination and … it is a new super-virus. For me, and others, too, the days of bowing and scraping before processing clergy and bishops is over. I, for one, will never kiss another purple ring.

It is a new day. There will soon be a new kind of church, whose inspiration will be aspirational. And the darkness will not overcome it.

The Daily Sip is a series of short-form essays written by Charles LaFond, a potter, writer, and fundraiser; who lives with his dog Sugar on a cliff, on one of the more than 400 islands in the Salish Sea, pondering and writing about how to be a better human, but often failing. And sometimes not.