On January 21, 2021, President Joe Biden continued an American tradition by attending a prayer service at the Washington National Cathedral. The event included a closing prayer from Presiding Bishop Curry. Since 1933, the National Inaugural Prayer Service has been a familiar part of the inaugural ceremonies, but even before the was a National Cathedral, The Episcopal Church prayed for—and with—Presidents. That tradition began with George Washington and the first inauguration in 1789.

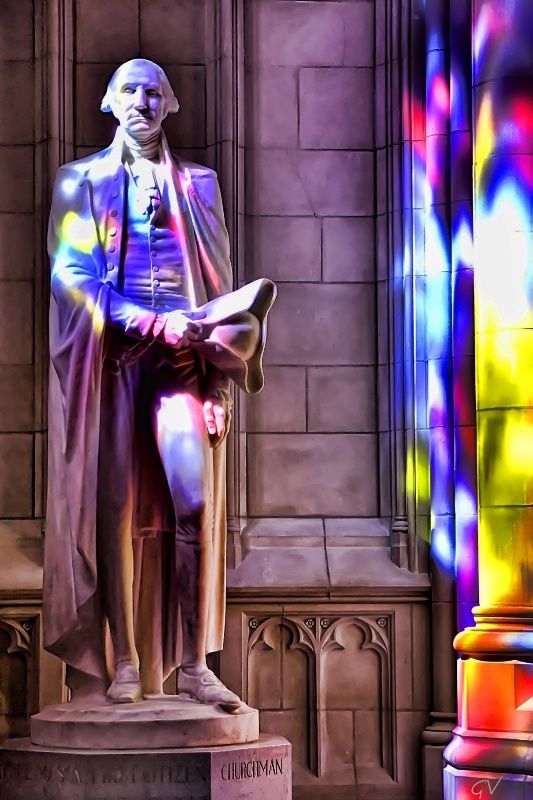

Washington took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York City, the nation’s temporary capital, on April 30, 1789. After swearing his oath, the new President and his wife Martha walked up Broadway to pray at St. Paul’s Chapel, now part of the Parish of Trinity Church Wall Street. The Episcopal Church officially acknowledged Washington’s ascension to the nation’s highest office, sending the new President a message on August 7, 1789. This message, offered by a developing church to the first president of a new nation, is worth considering as we greet with relief the continuation of our democracy.

It is not strictly the case that The Episcopal Church sent President Washington a message in 1789. “The Episcopal Church” did not exist in 1789, nor was there at that time a “Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States of America,” to use the old formulation. The General Convention of 1789 called itself “The Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and South Carolina.” That cumbersome label was necessary because five of the original 13 states chose not to send representatives to the Convention. Even those who attended the meeting were not sure Episcopalians needed a national organization. Not every diocese had a bishop, a situation William White, one of the founders of our church, called “the unfinished business of the episcopacy.”

Even so, the scattered leaders of what would eventually become The Episcopal Church were unanimous on one issue: George Washington’s character was the key to the nation’s future. Their address to the new President noted the “temperate yet efficient exercise” of the power Washington had commanded as a general. Washington chose not to set himself up as military dictator right after the war, an outcome that was often the result of eighteenth-century revolutions, leading the Convention to praise “the voluntary and magnanimous relinquishment of those high authorities at the moment of peace.” They were prescient, as the “voluntary and magnanimous” transfer of power was to be one of the regular miracles of American governance, although of late in jeopardy.

Washington was himself an Anglican, and then an Episcopalian, and had served on the vestry of parishes in Virginia both before and after the Revolutionary War. The Convention noted this denominational kinship, declaring, “We most thankfully rejoice in the election of a civil ruler deservedly beloved, and eminently distinguished among the friends of genuine religion; who has happily united a tender regard for other churches with an inviolable attachment to his own.” The phrase “genuine religion,” a reference to James 1:27, carried significant theological weight at the time. John Calvin had defined genuine religion in 1602 as confidence in God coupled with a fear that sprang from “willing reverence.” John Wesley preached in 1771 that genuine religion was “easily discerned” in two words: faith and salvation. The influential Anglican clergyman Josiah Tucker, well regarded in America for his support of our nation’s Independence, claimed in 1777 that genuine religion depended upon “a right employment of time and talents.”

That Washington understood “genuine religion” in the Episcopal tradition is reflected in his reply to on August 19, 1789. The new President thanked the Convention for its good will, declaring, “It would ill become me to conceal the joy I have felt in perceiving the fraternal affection which appears to increase every day among the friends of genuine religion.” Yet Washington was at pains to strike an ecumenical tone, adding that he was pleased “to see Christians of different denominations dwell together in more charity, and conduct themselves in respect to each other with a more Christian-like spirit than ever they have done in any former age, or in any other nation.” It is safe to say that Washington, raised on the Book of Common Prayer’s prayer leaders serve “in all godly quietness,” would have been puzzled by American’s turn to Christian nationalism.

When the National Cathedral hosted President Biden last week, The Right Reverend Mariann Edgar Budde, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, called upon the participants to “look toward the future with resolve and hope,” and to “seek divine guidance always, care for one another, and live according to the highest aspirations to which God calls us as individuals and a nation.” The prose is contemporary, but the aspirations are not so different from those of our Episcopal forebears of 232 years ago. They were living in an age of skepticism – not all believed that Americans were capable of peaceful self-governance. They asked God to help the President succeed for the sake “the restoration of Order, and our ancient virtues; the extension of genuine religion, the consequent advancement of our respectability abroad, and of our substantial happiness at home.” We are reminded that a great deal depends upon the character of the President.

Dan Ennis is a member of St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Conway, SC.