By David C. McDuffie

Since COVID-19 forever changed life as we knew it during the early months of 2020, we have become accustomed to hearing a constant refrain recognizing our anxiety, fears, and loss. This recognition has come from politicians and journalists, family and friends, official statements and casual conversations. I know that “I hope you are doing well in these strange times” became a staple of email messages I sent for quite a while.

Of course, we have heard these calls of lament from the pulpit or, more likely these days, from a Zoom box or Facebook feed. This is only appropriate as healthy and sustainable religious practice does not tell us that life will always be easy or that the circumstances of our lives will always perfectly correlate with our desires for them. The church needs to address difficulty. If it does not, religion risks becoming shallow and superficial and will inevitably crumble under the strain of adversity.

Yet, Christianity is also a resurrection faith, and a deep and abiding religious faith provides us with not only comfort in times of crisis but also, and perhaps more importantly, with hope for the future regardless of the current condition of our lives. It is important to remember this now that we have journeyed through the spiritual discernment and contemplation of Lent to the hope and renewal of Easter. Hope and confidence in God’s transforming grace and awareness of the blessings contained in silver linings are perhaps all the more important during this Easter season as we mark more than a year in the midst of a pandemic that has cost so many so much.

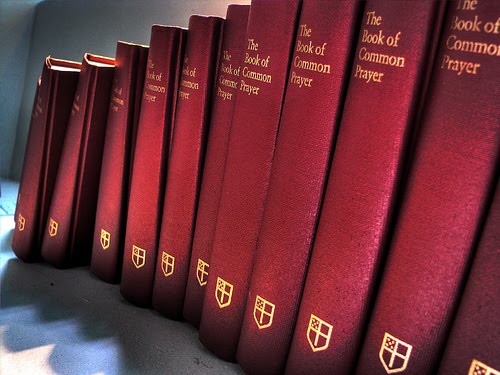

I would propose that one such blessing in these unprecedented times is our Book of Common Prayer. I think it is safe to say that many Episcopalians have a mixed relationship with the Prayer Book. We have slowly grown accustomed over the years to the rhythms and resonance of the liturgy of the Eucharist and the occasional Sunday repetition of our Baptismal vows. We browse through at various times looking for an appropriate prayer for a particular occasion. Perhaps we have even wandered in from time to time and found ourselves intimidated by what can initially seem like the spiritual calisthenics of the Morning Prayer service awkwardly flipping from page to page wondering how in God’s name everyone else seems to confidently and consistently find the right page. And, what exactly is a Canticle and how are we deciding which one we will be reading this morning? Maybe we have enjoyed the idea of the Prayer Book much more than appreciated the depths of spiritual practice that it offered.

In the last year, we have been presented with the opportunity to know the Prayer Book more intimately as friend and companion. While we have been, to varying degrees, separated from the Eucharist, the Prayer Book has been there for us offering community in isolation. In a time of great absence, it has served as a sacramental presence, an outward and visible sign of the presence of grace among us. In so doing, it has embodied for us the potential to realize that, despite distance, we are all connected and sustained by the mysterious yet abiding depth of a divine incarnational love.

The Prayer Book was with me when my father went into Hospice care this past summer. While it was the effect his cancer treatment had on his body and not COVID that ultimately led to his transition from this life, it was COVID that kept us from being with him in the ICU while he fought with a spirit much stronger than his failing body. When we were allowed in to see him, two at a time, during his final week, the Prayer Book was there as I read a recommended prayer, sent by my Rector, with my mother at his bedside and, silently, the Order of Compline at the close of an evening.

As in person worship was suspended at the onset of the pandemic, the clergy and staff at my parish began weekday online offerings of the Daily Office services of Morning Prayer and Compline. Somewhat ironically, in this case, the Prayer Book became a more prominent part of our worship life not in spite of but as a result of the conditions created by COVID-19. Such a realization prompted one of our members to point out during conversation following Compline one night that it was unlikely that we would have all been together had we actually had to drive to the church at 8:30 for the service. This online accessibility was all the more pertinent on January 6th when our Rector called our parish to gather for a parish wide Compline service as we all attempted to process the violence and apparent fragility of our democracy that had been so visibly on display at the Capitol earlier in the day. And so, the Prayer Book has continued to bring us together to gather as a community of prayer, during the week and on Sundays, in ways that we would not have been otherwise. Isn’t this togetherness, in itself, a prayer and where, when we connect with each other to learn how to live better together, we find God?

In Welcome to the Book of Common Prayer, Vicki K. Black writes that, in using the Prayer Book, “we discover we are not alone, and this liturgical current of worship, prayer, and praise will indeed take us where we want to go–union with the God we seek to love.” The pandemic has forced us to stand still in ways to which we are not accustomed, and in standing still, we have been given opportunity to become aware that prayer, at its most profound, is not something that we do as a transactional petition to a God “out there” but is, instead, becoming increasingly aware of the connections in our lives and letting the God, who is present all around and within us, to work through us. The Prayer Book has been there to assist us in this process. By entering the liturgies of the Book of Common Prayer, we are slowed down and attuned and oriented to the rhythms of God.

Of course, we can also struggle with the Prayer Book. Perhaps we may be troubled by a particularly jarring passage from Jeremiah or a confusing or even off-putting reading from the book of Revelation. For many, the patriarchal pronouns attributed so frequently to God give pause, and perhaps we change them as we read rendering them gender neutral. Or, maybe we read them as they are, accepting that God transcends any gender identity that we may attribute and anticipate that the language of future iterations of the Prayer Book will arrive more closely at the mysterious reality of the Divine. I find it helpful here to think of the words of my late professor, mentor, and friend, Dr. William L. Power. He would often remind me that we, as contemporary Christians, can, and sometimes should, disagree with aspects of the tradition, yet we should also respect and value that tradition as we are a part of it and have been shaped by it.

The Prayer Book is not perfect. But, when we enter its pages, it helps us to understand who we are and where we have been as a spiritual community. It grounds us in the present and allows us to reach out through time to all who have said some version of these prayers before us and all who will say them after. When we recognize the communion of saints, when we pray that those who have passed will rest in peace and rise in glory, we implicitly acknowledge the thin line between life and death and that they are still here with us in some mysterious way. Despite its imperfections, the Prayer Book offers us signs of grace in an uncertain world.

Liturgically, following the anxious anticipation for resurrection and renewal during Lent, we have once again arrived among the promise of the Easter season. There are also glimmers of light on the horizon indicating that our journey through the wilderness of this pandemic is beginning to ease in intensity. The potential of vaccines and our promise to continue wearing our masks give us hope. There is also hope to be revealed within the covers of the Prayer Book. It is there in the beautiful simplicity of Noonday Prayer and evening Compline and in a particular Canticle or Collect that speaks to us on a particular day. It is there in the more frequently used words of Rite II and in the distant yet resonant language of Rite I. Once we have been properly oriented and overcome our insecurities regarding page numbers and proper pronunciation and allowed the Holy Spirit to guide, it is also there in the spiritual symmetry of Morning Prayer and in any of the other corners of the Prayer Book that we may explore or be led to along life’s winding way.

Of course, while we were apart, we have all longed to return to the regular sacramental presence of a gathered community celebrating the Eucharist in the sacred spaces we call home. Yet, in our various absences during the pandemic, the Prayer Book has been there for us in ways that our primary formal sacrament frequently could not, reminding us with a quiet confidence that God’s transforming grace is still at work in the world. Once we are on the other side, let us hope that we will not forget this reminder but continue to explore the depth discovered and, in the words of one of the concluding sentences from Morning and Evening Prayer, “May the God of hope fill us with all joy and peace in believing through the power of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

David C. McDuffie is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies and a member of the Environment and Sustainability Program Advisory Council in the Department of Geography, Environment, and Sustainability at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He is also a Fellow at The Center for Religion and Environment at Sewanee: The University of the South and Chair of the Diocesan Committee on Environmental Ministry for the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina. He is a member of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Hillsborough, North Carolina.