I love to write. I suppose I’m not particularly good at it, but I do enjoy it. Now and again, something ends-up on paper that makes me stop and say to myself, “Now where in heaven’s name did that come from?” Mostly, though, I have one of four reactions to the product of my labors: satisfied with it; think it’s blather but maybe worth reading; want to edit the heck out of it; or decide to pitch it out.

One day wrote something I felt good about. It doesn’t happen often, and I soaked every bit of joy out of it that I could. Then I took a risk; I showed it to my boss, not as my supervisor but as a co-worker from whom I wanted to get an opinion as to whether or not it was any good. His comment? “I don’t believe in…,” and proceeded to tell me why he disagreed with some of the content in the piece. This was not the reaction I wanted, much less expected. I had no problem with his statement about his belief in something; he was entitled to express his disagreement with my thesis; still, it would have been lovely to hear just a word or two like, “Although I don’t agree with your beliefs, your expression of your position was good.”

An hour or so later, I decided to be honest with him. I walked into his office and told him that I felt disappointed that he didn’t say anything about the whole piece, just about something he disagreed with. His response really floored me. “I’ve been trying to think how to say this, but I’ll just say it. I thought the writing was brilliant, but I couldn’t help but think that I wished you were as good at your work here.” I know it was his nature to be a perfectionist, but how I wish he had stopped at the first part of the sentence and just left out the part that began with “…but…”

I still think about that incident from time to time. I remember a technique of having difficult conversations and how it was advisable to do a kind of “sandwich,” beginning and ending with something positive about another’s performance with a “but” in the middle representing something that needed changing. The sandwich is supposed to separate the actions from the self, making the statement more about the problem with the work, not about the person’s being or selfhood. Somehow, it’s supposed to cushion the bad news by first and last mentioning the value of something else. That does not always work. I wonder if I’m getting conditioned to listen not to the prologue but for the “…but…”

I don’t think Moses heard the burning bush announce, “I know you like the quiet life, Moses, but…”

I’m sure the angel wasn’t apologizing when speaking to Mary, “I know this is asking a lot, but…” as he stood in the middle of her family patio.

Jonah, on the other hand, did hear a celestial “but…”. “I asked you to preach repentance, and you did a great job, but…” Jonah was rather pissed at that “but.” He was all set for a nice conflagration or at least a significant plague or something, but, no, God got a repentant people, and Jonah didn’t get to watch the punishment he was hoping to see.

I guess even Job’s friends could have been guilty of “You’re a good guy, but…”

Martin Luther could have said, “I love this church, but…” That little conjunction can mean a whole shift in the line of vision.

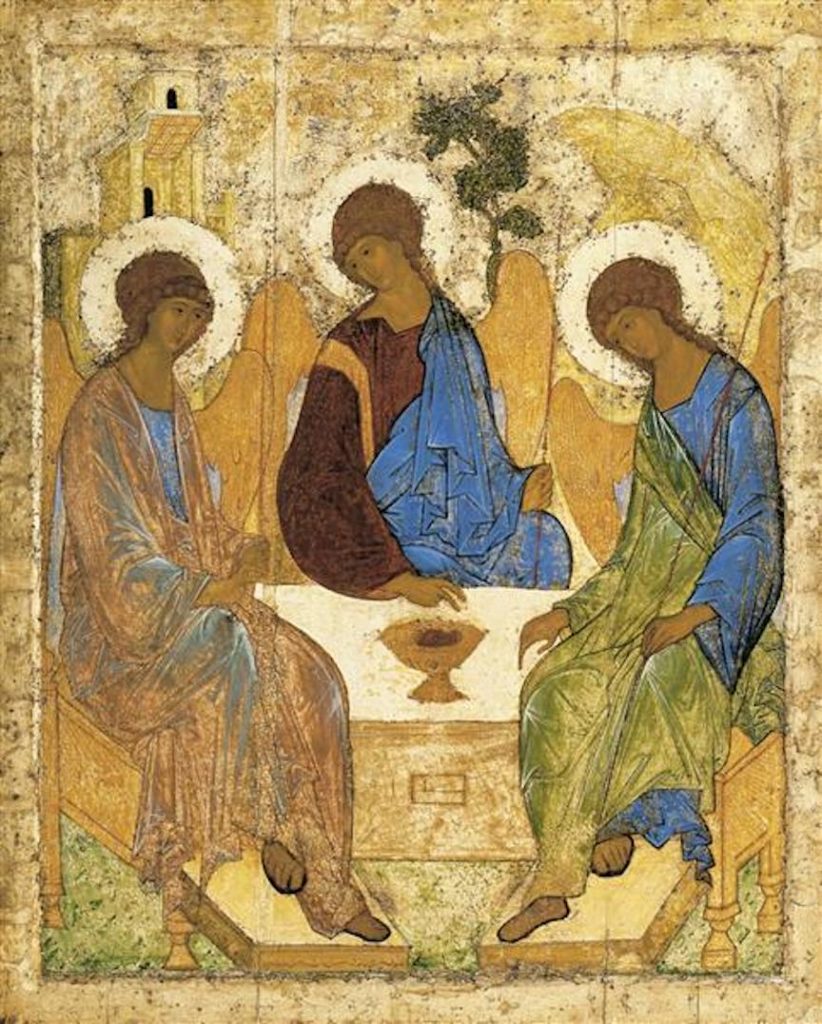

Today the church commemorates the Russian iconographer, Andrei Rublev, born in the 1360s. Of many icons that have been attributed to him, two, at least, have been authenticated as Rublev’s. One of these two is the famous icon called “Trinity.” It references the story of angels visiting Abraham and Sarah in Genesis 18. Rublev, however, left Abraham and Sarah out of the picture, so to speak, and instead focused on the three angels — or perhaps it was God and two angels. I wonder whether Rublev started to put them in, but God intervened, perhaps with words like, “Nice idea, Andrei, but do you really need more people in there?”

I wonder what might happen if, before we were to do something, a little voice in our mind would pop up with “But what if…?” We wish drunk drivers would ask themselves that before they put their key in the ignition, but we’re likely to end up bruised and shaken even if we say something. Perhaps we could talk ourselves out of bad habits we had, or maybe suggest trading fruit and a salad for that gorgeous big double cheeseburger that would play merry heck with our triglycerides.

What if Peter had said “but…,” before he jumped over the side of the boat and tried to walk on water as Jesus was. When James and Andrew joined Jesus, their acceptance didn’t include, “but give us time to go grab a sandwich” or “I need my good pair of sandals,” did it?

Where does “but” come into our lives, and how do we use it? We could buy a new car but we could also use that money to save toward the kids’ college fund. We could watch another half hour of TV, but we could also spend that time in prayer, study, or meditation. We could choose the easy way of doing things, but we could also choose to do them the Jesus way. We could focus on the poor and less fortunate rather than how many possessions (even knitting yarn) we could accumulate, or perhaps how to support someone who exemplifies the teachings of Christ instead of making church numbers indicate how Christ-like the group was.

Where does “but” fit in? How can it be used profitably, not necessarily financially? How can God insert that little word into our lives if we don’t give God a chance? This is something I will need to think about this week.

Image: Trinity, Andrei Rublev, ca 1410-20. Located at Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Found at Wikiart Visual Art Encyclopedia.

Linda Ryan is a co-mentor for an Education for Ministry group, an avid reader, lover of Baroque and Renaissance music, and retired. She keeps the blog Jericho’s Daughter. She lives with her three cats near Phoenix, Arizona.