written by Megan Thomas

On any given morning, as I drive into the central New Jersey town where I live, I pass clusters of men standing on the sidewalk. They are waiting for a contractor or landscaper or mover or restaurant to hire them for the day. Even in the dreariest days of the coronavirus pandemic this past spring, they waited there for work. And they were hired, because they are the ones willing to do the “essential” labor without social distancing or personal protective equipment.

Towns have tried to prevent their gatherings (such ordinances are generally unconstitutional), but because our economy depends on them, they are tolerated grudgingly. After all, how many other folks are willing to risk their health and safety to pick, push, lift, load, dig, cut, chop, scrub, stretch and stoop for our needs?

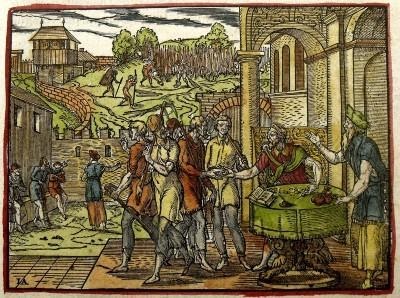

On Sunday we will hear the parable of the vineyard workers from Matthew’s Gospel. It follows on the Labor Day holiday of this past Monday. How timely. The kingdom of heaven can be compared to the employment practices of a certain 1st century landowner who had a vineyard. The landowner went to the marketplace where the day laborers would gather early in the morning to hire workers for his vineyard. He bargained with them for an agreed upon wage (a coin called a denarius), and they went to work. Throughout the day the landowner returned to the marketplace, recruiting more workers for his vineyard and promising them a fair wage. Even in the last hour of the workday, the landowner went back to the town square and found others standing there unemployed. He sent them into the vineyard, too. And at the end of the work day, when it was time to pay their wages, the landowner instructed his foreman to call up the last-hired and pay them first. But when the first-hired saw that all the workers were being paid the same wage, they muttered it was unfair.

Seems unfair to me, too. Fairness requires that we receive a fixed payment for a defined unit of work, right? Whether it’s piecework or hourly work. Even a lowly assistant manager at a big-box store, who works for a salary and commissions, knows how her employer measures the value of her work. In our economy, we value the output, the work product, the measurables. This is the rule of the marketplace we understand, and seems impartial and therefore just.

This is a parable, however, and not a law school case study on employment practices. The kingdom of heaven is not the marketplace. God does not assign value to the unit of labor or the output or the work product. God values the worker. Someone who is employed for one hour of the day has the same human needs as someone employed for the full ten hours. At the end of the day each of the vineyard workers received what he needed.

God knows we have needs—yes, certainly material needs such as shelter, food, safety, healthcare—but also needs that are not tangible—justice, mercy, forgiveness. The vineyard workers who worked all day and those who were sent at the last hour have the same needs, even if the first-hired, in their moment of anger and self-pity, do not recognize the gift bestowed on them by a loving God, and begrudge their fellows the same consideration.

Now because this is a parable, we may stretch our imaginations a bit, but it’s only a bit. What treasure will God grant us for our time in the vineyard? Is it not Jesus Christ, who gave himself as an offering and sacrifice for our sake, as the fair wage for our redemption, whether we come early or come late?

Image: Jost Amman, “The kingdom of heaven is like a householder,” woodcut c. 1570

The Reverend Megan E. Thomas is Priest-in-Charge at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Ewing, New Jersey, and an attorney in private practice.