by Megan Thomas

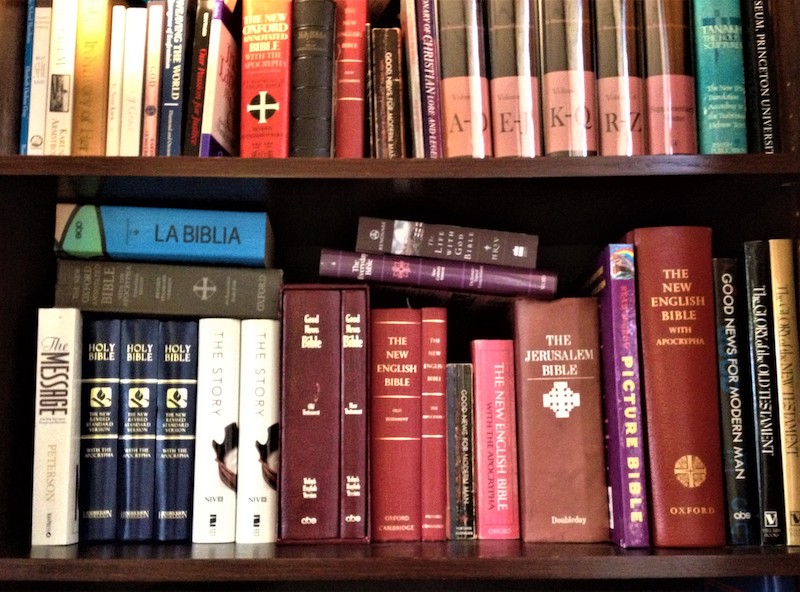

We take it for granted that anyone who is interested in the Bible should be able to pick up a Bible and read it. We give our children picture Bibles in simple language. We can find a Gideon Bible in most hotel rooms. You can read and study the Bible online: there’s an app for that—in fact, more than one. Surely you, too, have one on your hand-held device? You can find the Bible in any number of English translations—each with its own point of view, or ax to grind. (For as Italians say, “traduttore, traditore” – “to translate is to betray” the text and reveal the translator’s bias.) I have been told that there was a time when books were so costly, that people learned to read by using the Bible as their primer.

No doubt many of you reading this reflection have received and given Bibles for important life events. My favorite Bible gifts are, first, a Jerusalem Bible given to me by my grandmother when I was confirmed, whose onion skin pages crinkle a bit when turned and whose red ribbon bookmark is frayed to the point of uselessness; and, second, a splendid heavy almost-coffee-table-size Bible bound in red leather with illustrations by Salvador Dali given to me by my sponsoring church when I was ordained. I use them both. But I also have a palm-size Gideon New Testament with the Psalms, which for many years traveled around with me in a tote bag along with a rosary. Very useful for visiting the sick.

Recently I sat down for coffee with a young seminary student who is interested in learning about the Episcopal Church. He had been raised in a Church of Christ congregation out west and lived for a time in the Bible Belt. He had competed in Bible knowledge and memorization contests as a kid. I was quick to assure him, and a bit proud to say, that the Episcopal Church, in spite of what many people believe about it, is in fact a “Bible church.” After all, our congregations typically hear four readings from holy Scripture on a Sunday morning, according to the Revised Common Lectionary. There’s little room to pick our way around the assigned readings, even the ones that might set our teeth on edge. And those folk who devote themselves to saying the Daily Office do read long passages of Scripture over a two-year period, and can read all 150 Psalms over the course of seven weeks. And once a year, more or less, you will pray, “Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scripture to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life.”

According to Wikipedia (my apologies for tapping into this favorite source for all sorts of information), as of this month, the entire Bible has been translated into 683 languages. The New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,548 languages. We should give thanks that holy Scripture is available to so many people in so many formats. It was not always so.

Today the Episcopal Church remembers John Wyclif (c. 1330 – 1384), a parish priest and university professor, theologian and philosopher, dissident and translator. He was a contemporary, roughly speaking, of Chaucer and of Dame Julian of Norwich, and had a gift and desire for the vernacular. And although a man of many talents, and some political intrigue, we know him chiefly as the first to translate the entire Vulgate (Latin) Bible into English.

It was an era when only the educated few could read and understand the Bible; ordinary folk depended on the clergy to interpret the Bible for them. Wyclif held that believers should have a direct, unmediated relationship with God, not requiring the intervention of the church or its priesthood. He wrote, “The laity ought to understand the faith, and since the doctrines of our faith are in the Scriptures, believers should have the Scriptures in a language familiar to the people.” In other words, Scripture should be available to all who could read, in their own language. And to that end, in 1382 Wyclif and his assistants began to translate the Vulgate into English.

Did the Church welcome the translation into English? It did not.

How precious each Wyclif Bible must have been, and how dangerous for the possessor! Wyclif’s Bible was a manuscript—each translation was written by hand. (We should remember that Gutenberg did not invent his moveable type printing press until 1439.) Not so very many were produced, and the Church went to great efforts to eradicate Wyclif’s translation, yet hundreds of copies did survive.

Wyclif was fortunate to know people in high places. He had defended the English monarch in disputes with Rome, arguing that a national church could be fully and completely the church and not have to tolerate the interference and abuse of foreign (that is, papal) authority. Wyclif’s stature protected him from the anger of the Church, and though persecuted in his later years, he retired to his parish in Lutterworth where he died of natural causes in 1384. But the Church could not let him be, not even in death.

The Archbishop of Canterbury writing to the pope some years after Wyclif’s death said of him, “That pestilent and most wretched John Wycliffe, of damnable memory, a child of the old devil, and himself a child or pupil of Antichrist… crowned his wickedness by translating the Scriptures into the mother tongue!” In 1415 the Council of Constance declared Wycliffe to be a heretic, and decreed that his works be burned. Still that was not sufficient. Wyclif became a martyr of sorts after his death—surely it’s for this reason that the Episcopal Church denotes him “prophetic witness.” Would it surprise you to know that Wyclif appears in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563)? In 1428, under the direction of Pope Martin V, Wyclif’s corpse was exhumed and burned and the ashes dumped in the river. “But though they dug up his body, burned his bones, and drowned his ashes, yet the Word of God and the truth of his doctrine, with the fruit and success thereof, they could not burn.”

How appropriate that the Gospel appointed for today is Mark’s telling of the Parable of the Sower. “Behold, a sower went out to sow,” broad casting the seed exuberantly, in great fistfuls, heedless of where it might land—path, stony ground, thorn, good soil. For centuries the word has been and continues to be sown, sown far and wide, by means tangible and now intangible. Consider where it has landed. Today consider where it will still land. May it find in us good soil ready to hear the word and accept it and to bear fruit, thirty and sixty and a hundredfold.

The Reverend Megan Thomas is priest-in-charge at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Ewing, New Jersey, and an attorney in private practice.