Readings for the feast of Andrei Rublev, January 29, 2021:

Psalm 62:6-9, Genesis 28:10-17, 2 Corinthians 2:14-17, Matthew 6:19-23

In our Gospel reading today, Jesus says “The eye is the lamp of the body.” Perhaps the person who had the brightest view of the Trinity was the medieval iconographer, Andrei Rublev.

Rublev is one of those saints we know very little about, including exact dates of his birth and death. We place his birth at somewhere around 1360, and although dates of his death range between 1427 and 1430, most scholars and theologians settle on January 29, 1430 as the date, though some branches of Eastern Christianity celebrate his feast on July 4. Based on the geographic locations of original works attributed to him, it is believed he lived at the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra monastery near Moscow. His earliest attributed works appear around 1405, when it is recorded that he worked on icons and frescos in the Cathedral of the Annunciation in the Moscow Kremlin. The works are not solely his, however, as several other iconographers and artists such as Theophanes the Greek and Prokhor of Gorodets worked on them, as well.

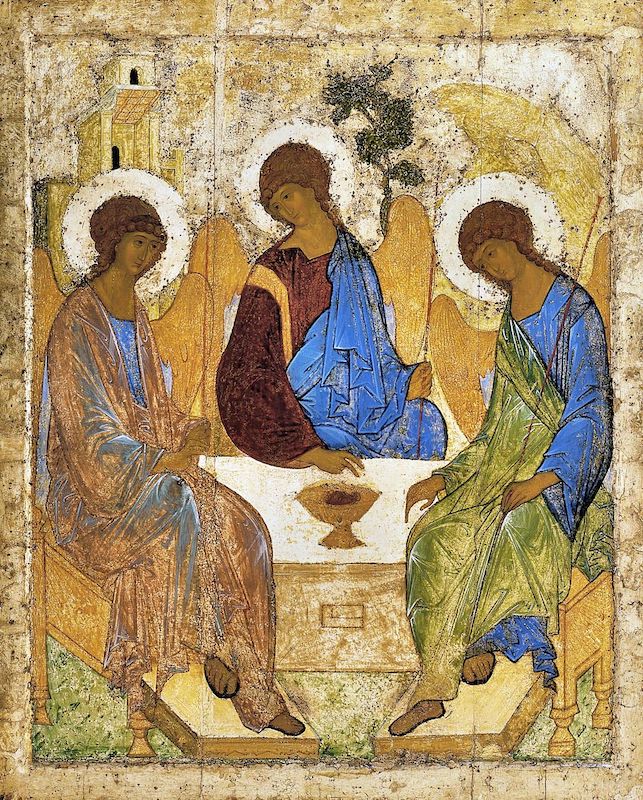

Only one icon is definitively his–his rendition of the Trinity. What stands out in this icon is the absolute serenity in the three faces of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, perhaps unimaginable for us in the present moment of our lives in 2021. Yet, the ancient principles of iconography itself mimic a truth of the power of God, the light shining in the darkness.

One principle of iconography is to create an invisible window into the Light of Creation from the darkness and chaos of the earth. The amount of preparation required to create a single icon is astounding. Rublev, who with the traditional iconographers, took great care simply choosing the board to be used, usually pine or linden wood. Next, the writer seals the board and covers it with a linen cloth, reminiscent of Christ’s burial shroud. The sealed board is covered with at least ten coats of gesso–a mixture of marble dust, chalk, and glue (usually rabbit skin glue or sturgeon glue). The icon is then transferred onto the gesso with a pointed tool. Red clay is applied to the areas that are to be gilded, then sanded and burnished.

Only now can the writer begin the gilding, which the iconographer breathes as much as applies it, much like the breath of God breathed life into humankind. A line is etched around the gold of the halo, and the red clay re-emerges into being as the red line around the halo. Paints to be used are made fresh–egg tempera–and natural materials are used for coloring, with three layers applied. Finally comes the finishing of the details and the final sealing of the board with linseed oil and a heavenly priestly blessing. (The entire process is saturated with continual prayer by the one writing the icon.)

When we look at Rublev’s icon of the Trinity, we are not only seeing the lamp of his eye, we are gazing at the life in his body–the skill of his fingers, the sealing of pigment by his own breath, perhaps even his own sweat dripping upon it as he worked. Many of us understand that the purpose of an icon is a window through which we can peer into the holy–but do we really understand that mystical union of our own human bodies as the frame of that window?

The next time you have an opportunity to pray through an icon that was made in the traditional manner, ponder the union of your own body through the bodily efforts of another human being to create that tiny peephole into God’s realm. What do you discover in your own breath, your own heartbeat, when you connect it to the life and breath of the one who created this window?

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri , as the Interim Pastor at Christ Episcopal Church, Rolla, MO.