by Larry Graham

We live in a period of worldwide renaissance. Events are moving more rapidly than ever before, the authority of institutions is being questioned, and the powerful are struggling to retain their power.

Renaissance can be defined as a period of rebirth that encompasses intense humanistic, intellectual, cultural and artistic activity. And more than mere human activity is present in renaissance. The Spirit is present, too: the finger of God moves more urgently in human activity.

The question of who is an Anglican (and conversely, who is not) fits well into the tenor of these times. Anglicans have often described themselves as being both catholic and reformed. This old description is a meritorious one because it is still the key to what Anglicanism is.

Catholic. The word means universal, in the sense of being all encompassing. To be an Anglican therefore, is to belong to a church to which everyone may belong. The early Church wrestled with this, and Saint Paul tells us the answer:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. – Galatians 3:28

So “all sorts and conditions of people” describes Anglicans very well. The single requirement for admission is baptism. Hopefully, any Anglican can ascribe to the ancient creeds and to church teachings. But that’s a matter of individual conscience and understanding. At our best, we follow Elizabeth Tudor’s good example and don’t try to make windows into people’s souls.

It’s a given that there are no tests to determine who is orthodox enough, or good enough, or even high church enough to belong. If you’ve been baptized, or want to be, you can be a part of the Anglican branch of Christ’s one holy catholic and apostolic Church. It is as simple as that.

It was not always so. The scriptures and our history tell us that. When God made Adam out of dirt and spit, and Eve out of Adam’s rib, the whole of creation was quite small: just God, two people, a garden and a snake. In time, God becomes the god of the Hebrews. And in the fullness of time, Jesus becomes incarnate and shocks his contemporaries by saying that even Samaritans and Gentiles aren’t beyond the pale. And for us, God becomes god of everything – and everybody. We’ve been trying to grow into that ever since.

Probably the greatest gift we have received from our new world-wide renaissance, at least so far, is a telescope named Hubble. It has made our view of the universe astonishingly larger. In comparison, Adam and Eve’s garden is really tiny, located on a small speck of a planet, situated in an insignificant solar system, on the outskirts of a galaxy that is just one of several million.

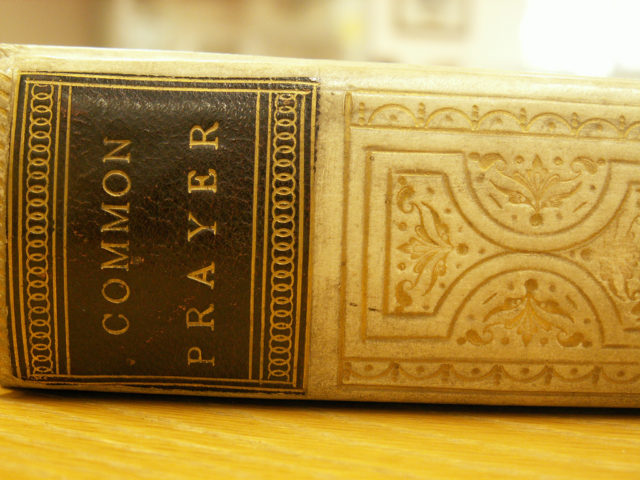

“At your command all things came to be: the vast expanse of interstellar space, galaxies, suns, the planets in their courses, and this fragile earth, our island home.” – The book of Common Prayer, p. 370

With Hubble, our concept of God has gotten bigger yet again. Our God is the creator and sustainer of all that! It is astonishing what wonders God has loved into being. And all of it (including us) enfolded in God’s loving arms.

Seen in this light, it is incomprehensible to make some exclusive claim to be the sole possessors of the God who made this awesome wonder, and certainly impossible to exclude anybody from it. To mirror that in our worship, communal life and polity, inclusiveness is an Anglican imperative.

So it logically follows that those who wish to exclude anyone from the Anglican way, also exclude themselves from it. Because being Anglican doesn’t mean just worshipping in a language “understanded of the people.” Anybody can do that, and still exclude anybody they want to exclude.

Instead, the Anglican way is to work at being as inclusive as God’s own all encompassing love, excluding none.

Reformed. The Reformation was the outcome of the Church’s experience with the Western Renaissance. It had its ugly moments, as princes of both church and state struggled to retain their hold on power.

But, a relatively swift outcome was achieved in England so far as the Church was concerned. Henry VIII disputed the Pope’s authority, Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer issued during the reign of Edward VI, Janes Gray reigned for nine days, Queen Mary Tudor briefly returned England to Roman Catholicism, and the Elizabethan Settlement all happened in about a quarter of a century.

In that period of doubt and turmoil the Church in England was transformed into the Church of England, the Anglican via media was born, and the Church was reformed at the beginning of the Age of Reason. Ecclesiastical things happened rapidly in that earlier renaissance.

Perhaps they are happening even faster now. The Book of Common Prayer, and additional forms of worship, the Hymnal and additional music are all available for download from the internet – our updated version of Gutenberg’s printing press. It is a dazzling array of resources. Given all these opportunities for new theological expression, it may be good to remind ourselves of what the preface to the first American Book of Common Prayer says.

“…in his worship different forms and usages may without offence be allowed, provided the substance of the Faith be kept entire; and that, in every Church, what cannot be clearly determined to belong to Doctrine must be referred to Discipline; and therefore, by common consent and authority, may be altered, abridged, enlarged …” – Book of Common Prayer, 1789

But there is a significant difference between Elizabeth Tudor’s time and now. The Western Renaissance affected primarily the ruling, ecclesiastical, and learned classes. Our ongoing worldwide renaissance affects nearly everybody on the planet. And virtually everything is being reformed in one way or another.

New occasions teach new duties;

Time makes ancient good uncouth;

They must upward still, and onward,

who would keep abreast of Truth…- James Russell Lowell

The Western Renaissance lasted about 300 years. If this current one began about 1950, we may have another 230 challenging years ahead of us, before things on this planet settle down a bit. The challenge before the Anglican Communion is to keep the faith entire while also proclaiming it in new ways to a rapidly changing world.

To do that, the “Jesus Movement,” (as our Presiding Bishop calls it) must move forward in the midst of renaissance. It must necessarily become what Christianity looks like in AD 2250 when 2250 gets here.

Only God’s Spirit gives new life. The Spirit is like the wind that blows wherever it wants to. You can hear the wind, but you don’t know where it comes from or where it is going. – John 3:8

We Anglicans can move forward in challenging times, be catholic and reformed, and be the church to a rapidly changing world, if we will but listen to the wind.

Larry Graham occupies a pew at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, Atlanta, Georgia.