I spend a lot of time thinking about the intersection between my faith and cultural expectations around apology, atonement, and forgiveness.

As I’ve written in other essays, a lot of what I see playing out has more to do with the offender trying to get through the situation as painlessly, for them, as possible. Their apology comes laden with unspoken conditionals: “I’m sorry (that I got caught). I’m sorry if I offended anyone (but I don’t really see how I could have you are just overly sensitive). I’m sorry for the pain I caused (but not really, I just want to get out of this as quickly as I can). Then, if they are a public figure and have a smart publicist, they fade away for a while and hope that their supporters and the people who pay for their products or performances will forget, or will shrug their shoulders and accept them back.

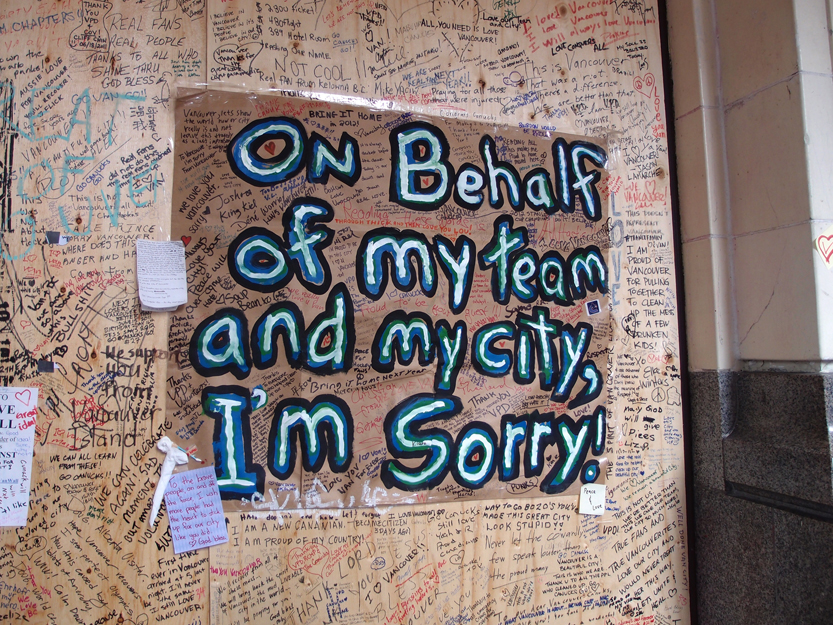

The apology in these cases is hollow to the core and does not contain the seeds that can grow into atonement or forgiveness. A true apology, a faithful apology plants those seeds.

In the offender, realizing that they have done harm can be the start of new growth. However it only works if the offender accepts that what they have said or done caused real harm. This doesn’t mean that the harm is proven valid by some neutral 3rd party. It means that the offender takes the person at their word, even if doing so makes the offender uncomfortable.

It can be very hard on the ego to have someone say you hurt them. It can feel like an attack. It is natural to react defensively to an attack; however, in the case of someone asking you to do better a defensive reaction is not helpful.

This is particularly important if the harm came from one’s own ignorance or carelessness. If I use a racial slur through ignorance and someone calls me on it I will learn more if I sit with the discomfort of being called out. I need to realize that it took energy and courage for the person to speak up — which likely means that I made them even more uncomfortable than I am at the moment. If someone takes the time and energy to tell me that I hurt them, the least I can do is believe them.*

Sitting with that discomfort, accepting it and working to understand its roots, and making a plan to change one’s behavior is work that is a necessary step in apologizing in a meaningful way. If I do this work, a good-hearted apology will flow naturally from it. If I don’t my apology will be empty.

Instead of a generic: “I’m sorry if you were offended” a more precise: “I’m sorry I used X language (or did X thing). Thank you for telling me so I can change.”

The work is not over once I made a thoughtful apology. If I am the offender I have follow up with atonement. I have to stop the behavior or the language that was hurtful. I have to change my behavior to be mindful of ways I can carelessly or ignorantly hurt others. I have to educate myself. This is one of many places where I can use my faith as a touchstone.

Am I loving my neighbor through my actions? (Not if what I do or say is hurtful.)

Am I respecting the dignity of every human person? (Not if I don’t take their concerns seriously when they raise them.)

Atonement isn’t walking on a bed of hot coals, or beating oneself up for making a mistake, or following the person around constantly apologizing and begging for forgiveness. Atonement is changing the behavior that caused the damage in the first place. Depending on how severe the issue was, atonement may also include reparations. Payment of time or money might be necessary to help repair the damage that was done; not as a punishment or a humiliation, but as much as a natural consequence of the damage.

Forgiveness is the gift of the harmed person to give or withhold. It is not something I can make them give me through any action of mine. Even if I fully apologize and rightfully atone, it can only come at a time of their choosing.

A big part of atonement is doing the work because it is the right thing to do, rather than as a way to ‘earn’ forgiveness. To my mind, forgiveness is more about the harmed person coming to terms with the damage that was done to them and reaching a point where they are at peace. It runs on a completely separate track and timeline than the actions of atonement.

That doesn’t mean that atonement has no impact. Depending on how severe the damage was, apology, atonement, and forgiveness might all happen within a matter of minutes or might take years, but active atonement will both help limit future damage and help the damaged person find their peace once again.

I have frequently seen a stronger emphasis on the need for forgiveness in the context of Christian faith; however, I think that we could do ourselves and the God who loves us a much better service if we focus on learning where we have gone wrong, apologizing with our whole heart, and using our newfound knowledge to change for the better.

—————-

*Note: none of this applies to known abusers using hurt/apology cycles as part of an abusive relationship, but that’s a whole different essay.

Kristin Fontaine is an itinerant Episcopalian, crafter, hobbyist, and unstoppable organizer of everything. Advent is her favorite season, but she thinks about the meaning of life and her relationship to God year-round. It all spills out in the essays she writes. She and her husband own Dailey Data Group, a statistical consulting company.

© 2019 Kristin Fontaine