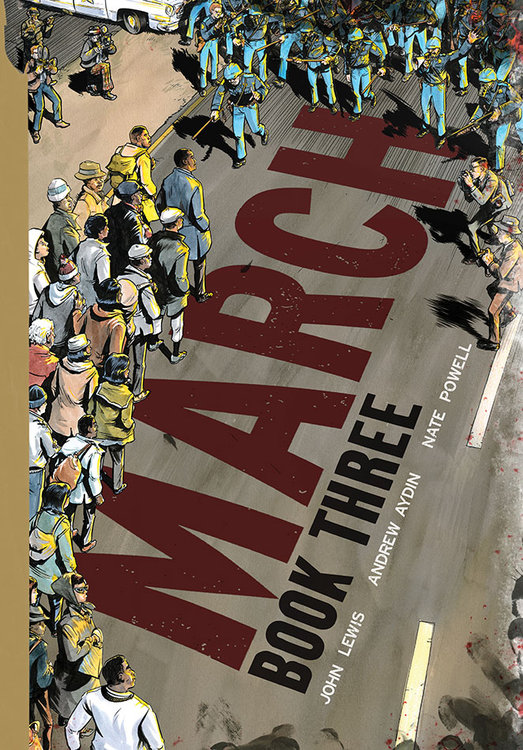

The third volume of “March,” a comic book trilogy based on Congressman John Lewis’s experiences during the civil rights era, has just been released, following books one and two (published in 2013 and 2015), and faith, church and hymns are part of the story. From WNYC:

It was only 53 years ago that four little black girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. This is where the final installment of Congressman John Lewis’ (D-GA) graphic novel, “March,” begins.

Over the next two hundred pages or so, readers are immersed in a series of events that helped shape America’s current racial and political climate. We are given a bird’s-eye view of protests that occurred in the deep south in the early 1960s, including the march on Selma and over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where Congressman Lewis thought he would die.

Religion News Service interviewed the three who created the book – Lewis, congressional staffer Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell, 38, and they talked about the significant role that church and church music played in the activism of the ’60s:

Q: Representative Lewis, in an earlier book of this series we read that you were asked by church leaders to tone down your speech at the 1963 March on Washington. How does “March: Book Three” deal with issues of faith?

Lewis: “Book Three” tells a story how people kept going, how people never gave up or gave in, in spite of the bombing of a church, the beating on the bridge as we had left church to march all the way from Selma to Montgomery. We kept going, we never gave up, we never gave in, we never became bitter or hostile. We kept the faith. It was the music of the church that lifted us, that carried us. … We felt like God Almighty was on our side.

Q: The book series often talks about how prayers and hymns were used ahead of and during the civil rights marches. What difference did they make for you personally?

Lewis: The prayers, the songs, the hymns fortified me, made me stronger, gave me the power and the ability, the capacity to keep moving, to pick ’em up and put ’em down. If it hadn’t been for my belief in God Almighty, the civil rights movement and my own participation would have been like a bird without wings.

The timeliness of the publication is apparent to its creators and to its readers. From a review in the Washington Post:

Last month, the second installment in this gripping trilogy received the Eisner Award — the nearest thing to an Oscar for comics — for Best Reality-Based Work. This month, the even-more-accomplished “March: Book Three” culminates the mid-’60s drama that spans from Albany to Alabama.

What the authors achieve with this conclusion is a window into living history that could not resonate more deeply in a year of political conventions against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement and its many battle lines of engagement.

Lewis himself considered ministry as well as politics, and chose the latter route. From a 2013 National Public Radio piece, describing the narrative of book one:

It begins with John Lewis as an old man waking on a dark early morning in Washington, D.C. It’s 2009, the day of President Obama’s inauguration. Quickly the reader is sent back in time ― to Lewis’ childhood, when he was taking care of his sharecropper parents’ chickens, practicing sermons on the young birds.

The pictures are black and white, and graphic artist Nate Powell renders Lewis’ life in shadow. Powell says he drew the story close to the ground, the way a child would experience the world.

“I could simply slip into his shoes for that moment,” Powell says, “and I knew precisely what it was like to witness the baptism of these chickens ― the loss of a beloved hen down a well. The hiding under the porch so that he could sneak away from his house in order to get an education each day and hop on the bus, with his mom chasing after him.”

The New York Times explains some of the inspiration behind the trilogy – a comic book published nearly 60 years ago, which Lewis read when he was 18 years old:

The genesis of “March” can be traced back to “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story,” a 16-page, 10-cent comic book published in 1957, which advocated nonviolent resistance. In 2008, Mr. Lewis told Mr. Aydin, his digital director and policy adviser, how influential the comic book had been on him and the civil rights movement. Mr. Aydin, who wrote his master’s thesis on it, to convinced Mr. Lewis to tell his own story as a graphic novel.

Today, this new story may be inspiring more young people in a new era of civil rights protests:

The creators of “March” are most heartened by their youngest fans. Mr. Aydin recalled an interview with a reporter for The Wall Street Journal who shared the graphic novel with his son. “His 9-year-old son had gone and put on his Sunday suit and was now marching around his house demanding equality for everyone,” Mr. Aydin said. “Imagine if we could instill a social consciousness in every 9-year-old in America. What would that do in a generation?”