by Becky Schamore

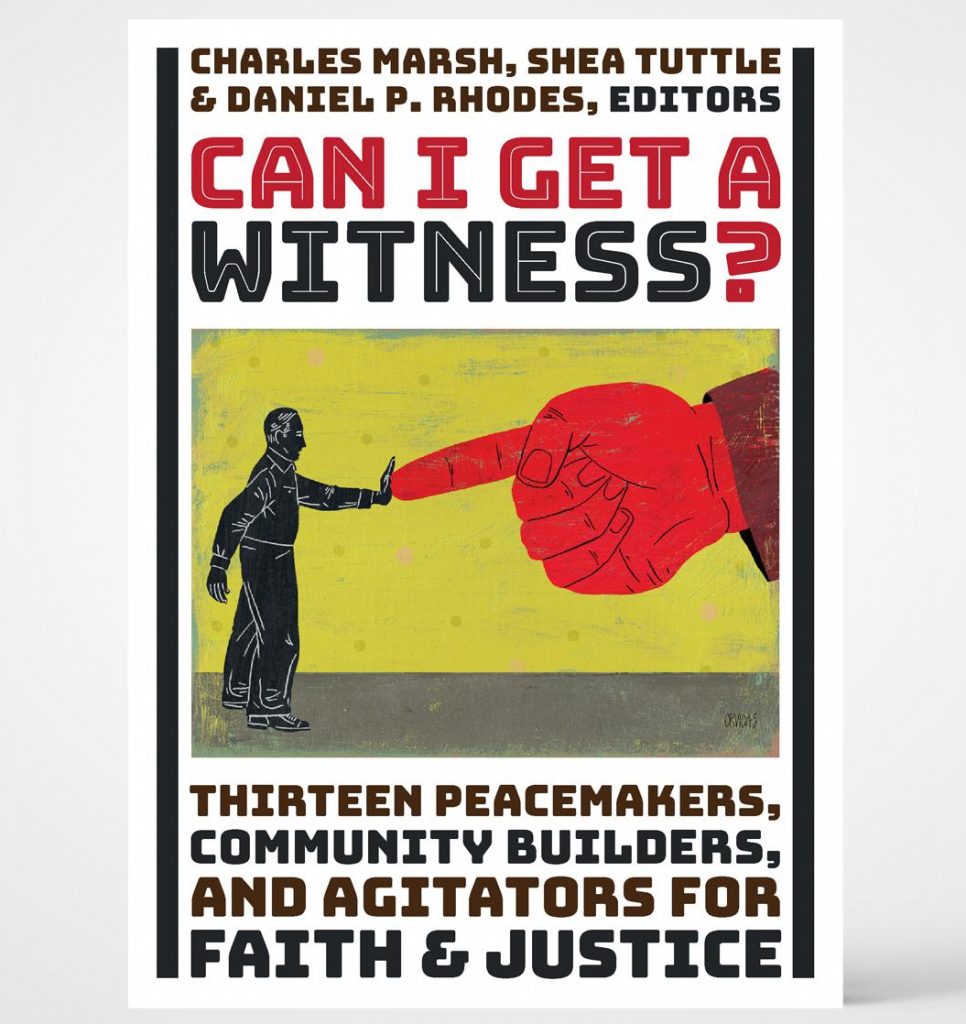

For anyone looking for light summer (or any season) reading or easy uplifting inspiration, Can I Get a Witness? Thirteen Peacemakers, Community Builders, and Agitators for Faith and Justice is probably not that book. I do not think it is meant to be. Don’t get me wrong, this collection of essays is certainly inspirational, but it is meant to be considered thoughtfully, meaningfully, and I would argue, slowly. The selections are intense—compelling stories (as the book jacket indicates), thoroughly researched and documented—you can’t just breeze through them. I couldn’t, anyway. I tried. I admit when I sit down to read a book, I often go through it once quickly to get the gist, then again more slowly to revisit specific passages. This book stopped me the first time. There is so much to digest and learn in each essay that I couldn’t finish Daniel P. Rhodes’ essay on Cesar Chavez one minute and then turn the page and start reading Donyelle C. McCray’s essay on Howard Thurman in the same sitting. This forced slowing-down is surely intentional. This book wants us to stop and pay attention to each essay, to listen and to learn from the peacemakers and agitators of the title.

The editors—Charles Marsh, Commonwealth Professor of Religious Studies and director of the Project on Lived Theology at the University of Virginia; Shea Tuttle, editorial and program manager of the Project on Lived Theology; and Daniel P. Rhodes, clinical assistant professor of social justice at the Institute of Pastoral Studies, Loyola University Chicago—have collected here a rich array of stories. Bringing together thirteen different writers to share their accounts of the fearless men and women, gay, straight, Catholic, Protestant, of different racial backgrounds, who inspired them by their tireless, peaceful activism to change American culture. The different writers’ stories are not only anecdotal, each essay is also thoroughly annotated with an appendix of notes and resources listed by essay at the back of the book. The editors include a detailed index of events, activists, organizations, and photographs, as well as brief notes on each contributor. The editors also provide an audio companion to Can I Get a Witness in the form of individual podcasts where, according to the website livedtheology.org, Shea Tuttle talks with the different authors about “the person they profiled for the book and about their writing process.” On the website, you can also find a comprehensive Lenten study complete with scripture, questions to consider, and additional resources. The book is not a quick read even if you skip the ancillary materials, but with the rich additional materials, Can I Get a Witness? provides the reader a strong foundation for study, reflection, and inspiration.

The stars of the collection are, of course, “the peacemakers, community builders, and agitators” themselves, men and women who never set out to be stars, who only ever wanted to make the world around them a better place. To many, their names are familiar and well known: Cesar Chavez, Howard Thurman, Mahalia Jackson. To others, like myself, some names may be less familiar, such as Yuri Kochiyama, Howard Kester, Ella Baker. Regardless of what we think we know about any of these individuals, the different authors provide unique insight into the how and why their subjects impacted them, adding new perspective to our own understanding of these faith-filled activists, be it broad or narrow.

The decision to ask different writers to share their accounts of who inspires them brings an added depth to the collection. Not only do the writers and subjects change, but the writers’ styles change as one writer employs more anecdote or conversation, while another one provides us with more of his or her personal connection to the subject, all of which adds to the overall variety of the collection. Readers will have to choose for themselves which stories most inspire them—whether that decision is based on the subject matter or the writing—Here are a few that spoke to me:

The collection begins with Daniel P. Rhodes’ essay, “In the Union of the Spirit: Cesar Chavez and the Quest for Farmworker Justice.” Having taught Chavez’ letter on the tenth anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., I thought I was somewhat educated about Chavez and his activism on behalf of farmworkers. Rhodes begins his account by juxtaposing the somewhat “unimpressive” physicality of the man with the “heroes of popular Westerns playing during the time that he was organizing farmworkers in southern and central California” (9). Rhodes’ point is obviously not to deprecate Chavez but instead to signal the power of his commitment. Whether he lacked the heroic presence of “a Roy Rogers or a John Wayne,” whether he matched Malcom X or Martin Luther King, Jr. in oratory skills mattered little compared to the “calm, fortified nature of his presence.” Rhodes details the devoted faith of Chavez’ grandmother and mother and their profound influence on Chavez. He recounts the loss of the family homestead in 1938 when Chavez was eleven years old and its lasting impact. ‘“From that point on he carried with him an abiding homesickness.” He quotes Chavez’ own recollection of how the loss changed him:

“Maybe that is when the rebellion started. Some had been born into the migrant stream. But we had been on the land, and I knew a different way of life. We were poor, but we had liberty. The migrant is poor, and he has no freedom.”

This glance back to the people and the circumstances of Chavez’ youth help the reader understand Chavez’ commitment to the farmworkers, his willingness to forego his own financial security to live “with and among the people,” and his steadfast rejection of organizations that do not put the farmworkers before themselves (18). Rhodes’ account is thoughtful and thorough, an in-depth look at the man whose fight for human dignity remained peaceful, personal, and sacred. For the most part, the writer removes himself from the narrative, but in the last paragraph Rhodes acknowledges Chavez “as an icon of what faith-based organizing can do.” Rhodes suggests that we can learn from Chavez’ activism and spirituality how to work toward the “kind of country for which Christians long.” This is the kind of observation that makes the collection more than a retelling of significant people and significant peacemakers. We are meant to recognize each of these witnesses and bear witness ourselves.

The second essay in the collection, “Setting the Captives Free: Yuri Kochiyama and Her Lifelong Fight against Unjust Imprisonment,” begins with a pledge and prayer made by the young second-generation Japanese American when she was eighteen years old:

To live a life without losing faith in God, my fellowmen, and my country; to never sever the ties between any institution or organization that I have been a small part…To never humiliate or look down on any person, group, creed, religion, nationality, race, employment, or station in life. . .

The author, Grace Y. Kao, acknowledges that in 1939, young Kochiyama had not yet been fully tested with respect to her creed. But with the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent arrest of her father, followed by the whole family’s “detainment” in a Japanese internment camp, Kochiyama’s faith and will would be tested again and again. The author cites the experience in the internment camp as a source of “new-found pride Yuri developed for her community’s resilience in the midst of great upheaval and suffering.” The author relates Kochiyama’s experience as the beginning of her recognition of the realities of “racially motivated incarceration,” a recognition that taught her not only to champion injustice but to “advocate” on behalf of those wrongly imprisoned. While interned in the Jerome camp in Arkansas, Kochiyama inspired her Sunday school class to begin a “massive letter-writing campaign to help (indirectly) with the war effort and to lift the spirits of all those evicted, forcibly removed, and incarcerated by [President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066].” This campaign spurred others; through these efforts Kochiyama learned to “recruit volunteers, motivate people around a common cause, and handle logistics.” Her activism crossed all racial lines, noting the similarity between the racism against Japanese Americans during World War II and that against African Americans in the Jim Crow South. She participated in the “non-violent takeover of the Statue of Liberty on October 25, 1977, to draw attention to the plight of Puerto Rican political prisoners.” She rallied behind David Wong who was wrongly convicted of murder in 1987 and released in 2004; she became a close ally of Mumia Abu-Jumal, convicted of shooting a white police officer, Daniel Falukner, but by his supporters, believed to be a political prisoner due to his “grassroots organizing with the Philadelphia Black Panthers Party” and other activism associated with violent conflicts.”

Kao cites religious conviction as a foundation to Kochiyama’s work. “As with her Sunday school teaching pedagogy, Yuri believed the mark of Christian discipleship lay more in love and service to others than in the instilling or proselytizing of doctrine.” The author supports this argument while noting the (mis)perception that Kochiyama drifted from her Christian faith when she stopped teaching Sunday school in the 1960s and practiced Sunni Islam from 1971-1975. Kao argues, “Whatever the content of Yuri’s confessional religious beliefs or understanding of her own religious identity, it is worth noting that she neither lost her connection to the institutional church nor ceased rendering the service to others the Christianity of her youth had first taught her to provide.” It is a lesson for all of us. “She continued to volunteer at soup kitchens and homeless shelters in various New York City churches and also taught English conversation to international students at Riverside Church in Harlem for most of the 1980s through the mid-1990s.” According to Kao, the lesson from Yuri Kochiyama “was never principally about dogma but about … service to our fellow human beings.”

One of the more personal essays in the collection was written by Soong-Chan Rah, Milton B. Engebretson Professor of Church Growth and Evangelism at North Park Theological Seminary. Rah was with Richard Twiss the week before he died, and his essay, “Standing Tall: Richard Twiss, a Witness to Native American Humanity,” resonates with the poignancy of loss. Like the other essays, Rah provides a thorough biographical account of Twiss’s life and call to activism, but Rah’s essay is rich with anecdotes that lend a particularly vibrant presence to Twiss. He appears on the page through his personal account of his conversion to Christianity: “The effect of the drugs left, the fear disappeared, and the most incredible sensation of peace flooded my being from the top of my head to the bottom of my feet. . . I became a follower of the Jesus Way.” But, as Rah recounts, the process of trying to assimilate into the “dominant-culture Christianity” was confusing. In fact, it didn’t work. According to Rah, “As [Twiss] traveled through the wide world of Christianity, he recognized the captivity of American evangelicalism to the standards and values of Western, white culture. He recognized that blending the ideology of nationhood, the Christian religion and the presupposition of American exceptionalism was a clear expression of syncretism.” Twiss worked to rid North American Christianity of its narrow confines, to bring to light the cultural genocide of Native Americans, to “make visible the formerly ‘invisible’ story of humanity and culture of the Native American community.” He spoke for his people. Rah writes with raw emotion about the loss of this minister of “racial reconciliation.” He reminds readers of the danger of an American evangelism based on “triumphalism and exceptionalism” where the American church reflects the exceptional nature of American society.” This “exceptional nature” according to Rah is essentially rooted in “the American Christian imagination of white supremacy,” a place where ‘“Make American Great Again” [means] to return to a previous state when it was dominated by white Christians.” For believers of all colors, Richard Twiss was a voice of reconciliation. According to Rah, he was “our humanity.”

The truths of these essays are complex and many-faceted. They are sometimes hard to read, always thoughtful. The essays are dense with detail and the specifics of the organizations that these activists participated in, created, lobbied for and against. If I didn’t pay attention, I would turn the page and not remember what an acronym stood for. I learned to read with a pencil in hand, so I could write notes in the margin. If you want a light read, this is not it. If you want to learn, if you want to be challenged and moved and inspired, if you want to be a witness to what it really means to stand up for what you believe and to transform American culture into a culture of faith and hope, this book may be just what you need to begin your own prophetic witness.

Becky Schamore is a writer, English teacher, and member of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Kingsport, Tennessee. She holds an MFA in Writing from Spalding University.