by Elizabeth Felicetti

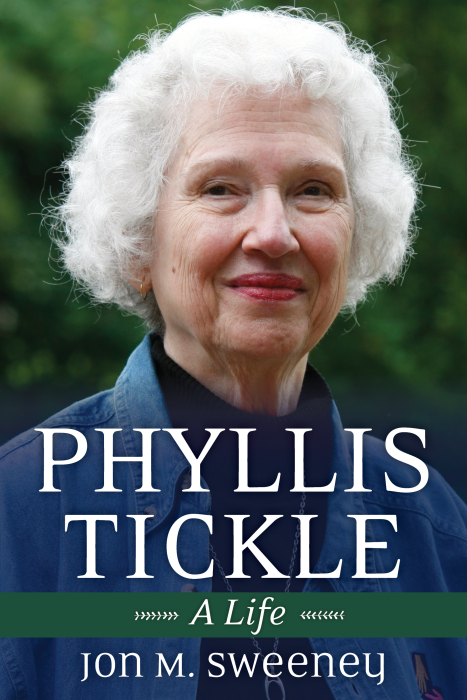

Phyllis Tickle: A Life, by Jon M. Sweeny, Church Publishing 2018

Phyllis Tickle was a sought-after speaker on the Episcopal diocesan convention cycle as well as other religious gatherings for years, and her three prayer manuals, The Divine Hours, were bestsellers among Christians of all denominations. A leader in the Emergence Christianity movement, Tickle made famous Bishop Mark Dyer’s assertion that the church has a giant rummage sale every five hundred years. Phyllis Tickle: A Life is her authorized biography by Jon Sweeney, with whom she had collaborated on The Age of the Spirit shortly before she died at 81 in 2015. Sweeney is the author of many religious books, including several about Saint Francis.

An authorized biography by a friend could result in a cloying hagiography, but Sweeney writes about Tickle honestly, flaws and all. For example, with respect to Tickle’s autobiography Shaping of a Life, Sweeney observes “a lack of candidness and revelation in the writing…little vulnerability or surmounting, important qualities in successful memoir” (145). He adds, “A kind of dishonesty…prevails, as she has nothing critical to say of anyone” (146). Fortunately, we are not subjected to such uncritical writing in this biography. Sweeney’s admiration and affection for Tickle are clear, but he’s willing to write about her honestly, not shying away from difficult topics such as her husband Sam’s bisexuality, which Sweeney did not know about until after Tickle’s death, nor Sam’s struggles with depression, as well as dementia in his later years.

As Tickle’s official biographer, Sweeney’s sources include not only her autobiographical and other writings and interviews with friends and colleagues, but also her personal correspondence and interviews with Tickle herself as well as her family. The book is organized roughly chronologically, so the reader learns about the books, forbidden to her in adolescence, that she furtively read anyway (Hedda Gabler by Ibsen and Dore’s illustrated Inferno), her marriage to Sam Tickle, who became a doctor, and her giving birth to seven children. The death of her son Wade as an infant leads a poignant chapter, “Anesthetizing Grief.” Subsequent chapters detail her poetry writing and small press publishing, her work as the founding editor of the religion department at Publishers Weekly, her unsuccessful attempt to write a mystery featuring “an Episcopal canon missioner who solves crimes” (101; she got to keep the advance), and then on to her successful best-selling prayer manuals (the chapter “Prayer Manuals and Mysticism” is especially riveting), her fascination with and promotion of Emergence Christianity, and finally the death of her husband and her own final months.

Perhaps most interesting to Episcopal Café readers will be the second half of the book, which in addition to recounting Tickle’s life also explains trends in spiritual writing, the publishing industry, and church, as well as details about Tickle’s spiritual life. We proudly claim her as Episcopalian, and she always claimed the Episcopal Church right back; but, Sweeney writes, “Phyllis’s Episcopal Church experiences…never satisfied her desire for deep, personal relationships. The lack was epitomized for her in the cliquishness of the ‘passing of the peace’ at every eucharistic service. When others turned and smiled and shook hands with those around them, Phyllis would try her best to do nothing, to greet no one in what felt to her like an artificial replacement for the real demands and possibilities of church” (148-149). At one point, Sweeney writes, Tickle and her husband felt called to join a LGBTQ congregation, so become involved in Holy Trinity Community Church. Tickle claimed they were there as “missionaries for the Episcopal Church” (155), but even though her husband transferred his membership, Tickle retained her membership and license as a eucharistic visitor with Calvary Episcopal in Memphis. To Tickle’s disappointment, Holy Trinity eventually became affiliated with the United Church of Christ rather than the Episcopal Church.

Tickle felt called to Holy Trinity because full inclusion of LGBTQ Christians in the Episcopal Church was vitally important to her, and the chapter “Behind the Scenes at LGBTQ” illustrates this passion. Such topical chapters, however, can make the biographical timeline confusing, so readers may sometimes become a little lost about where they are in Tickle’s life. Overall, however, Phyllis Tickle: a Life is recommended for anyone who loved The Great Emergence, the Divine Hours, or who was privileged to hear her speak.

Elizabeth Felicetti is the rector of St. David’s Episcopal in Richmond, Virginia and pursues an MFA in Writing from Spalding University. She tweets @bizfel.