by Carlo Uchello

“In the United States today, there are several million veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of us are wounded physically, psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually.” That’s not the kind of statement that you’d necessarily expect to hear from your local Episcopal priest, but these are words written by David W. Peters, author of Post-Traumatic God: How the Church Cares for People Who Have Been to Hell and Back. Peters currently serves at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Austin, Texas, and he has the experience to state those words with conviction. And for almost a decade, he’s put veterans at the forefront of his ministry.

“In the United States today, there are several million veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of us are wounded physically, psychologically, emotionally, and spiritually.” That’s not the kind of statement that you’d necessarily expect to hear from your local Episcopal priest, but these are words written by David W. Peters, author of Post-Traumatic God: How the Church Cares for People Who Have Been to Hell and Back. Peters currently serves at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Austin, Texas, and he has the experience to state those words with conviction. And for almost a decade, he’s put veterans at the forefront of his ministry.

Peters enlisted in the Marine Corps after high school, but it wasn’t until after his service that he attended seminary. He was later commissioned a chaplain in the Army, served as a battalion chaplain, and was deployed to Iraq in 2006. His first book, “Death Letter: God, Sex, and War” is being made into a motion picture. Some of his personal experiences in war are sprinkled throughout his latest book, which is published by Morehouse Publishing. Its subtitle, “How the Church Cares for People Who Have Been to Hell and Back,” is really the focus of this book.

Even though they are not directly engaged in combat, Army chaplains can suffer trauma from being exposed to war. You might even argue that chaplains have their special flavor of trauma to endure. It can surely be traumatic enough to witness or participate in the carnage and brutality of war, and to witness men and women intent on killing rather than being killed. But chaplains also must contend with the emotions and trauma of others, in ways that no divinity school could possibly prepare them. As Peters writes of soldiers who suffer from the trauma of armed conflict, “War shatters their connection to their pre-traumatic identify.” And others have argued that the issue of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is primarily an issue of grief. Post-traumatic people need a post-traumatic theology to help them in their time of greatest need, and the central focus of this book is how they can learn to deal with this grief.

Peters quotes from Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist who works with Vietnam era veterans, who wrote how the trauma of combat will produce symptoms in people that include the expectation of betrayal and exploitation, the inability to trust others, despair, isolation, and meaninglessness. If these symptoms remain untreated, this can separate the veteran from being able to fully participate in life with others. Shay writes that combat trauma “shatters a sense of the fullness of the self, of the world, and of the connection between the two.”

What veterans need most is a connection to a community and to God so that they might be able to recover their sense of trust and acceptance, for as Peters says, those who have taken part in a war are marked by it forever. Peters states that churches are often the best-equipped places where veterans can have these deep-seated needs met and sustained. As nice and as pleasant as it can be for veterans to be taken on the occasional camping trip or fishing outing, or to be invited to a barbecue, by themselves these are not sustaining communities for our veterans. The author makes the point that today’s churches must find a way to restore veterans from their own trauma, whether their trauma is caused by a sense of guilt or shame, and welcome them back into the community of God’s people. As Peters states, “Post-traumatic ministry is listening, and everyone can do it.”

Peters is convinced that churches can, and should, take a more active role in helping those traumatized by conflict. After all, he asserts that the New Testament is a post-traumatic book written by a post-traumatic community. That trauma, of course, was the crucifixion. You only need to be reminded that after the crucifixion, we learn in the Gospel of John, Chapter 20, the apostles hid themselves for fear of meeting the same fate as their leader, as in fact several of them did. Peters writes that “The anxiety of impending doom is crippling and is the hallmark symptom of PTSD.”

In 2009, the Episcopal Church’s General Convention encouraged every diocese to form their own Episcopal Veterans Fellowship. David Peters started and led an Episcopal Veterans Fellowship at St. David’s Episcopal Church in Austin, Texas. His sessions drew a mixture of veterans, including Vietnam-era veterans as well as ones from the more recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Typically, each session included a meal or snack, a sharing of the participants’ experiences and struggles, a period of lamentation in which a veteran shares their expression of grief or sorrow through a poem or a song or other creative work, and then concluded with a recitation of the Office of Compline.

Peters found inspiration for his ministry through the life and writings of Paul Tillich, who himself served as a chaplain in the German army in WWI and who was hospitalized three times for combat-related stress. Tillich acknowledged that, even as a chaplain, he spent more time in digging graves than he did distributing in the sacraments. For Tillich, being healed meant being grasped by the absolute, that is, by God.

A recent paper by three economists found that wartime trauma often turns people to God. For 18- to 24-year-olds who have directly engaged the enemy in combat, they are 5.7% more likely to attend religious services than those who have not. (Interestingly, enlisted soldiers who have directly engaged the enemy are overall more than 3% more likely to attend religious services, while officers are 2% less likely to attend religious services.) Perhaps, for some veterans, they have experienced the truth of what Karl Barth wrote in his sermon, “Saved by Grace,” when he said “To be saved does not just mean to be a little encouraged, a little comforted, a little relieved. It means to be pulled out like a log from a burning fire.”

In the end, “Post-Traumatic God” succeeds in convincing the reader that the needs of veterans are unique and that the church has a special role to play in helping to restore veterans to both God and to community. It’s not a “how-to” book, nor was it intended to be a guide for those interested in such a ministry. Even though most of us may never have an opportunity to engage veterans in such a community-building program such as the Episcopal Veterans Fellowship, we can gain powerful insights about how trauma of any kind can lead to an estrangement, and how estrangement can to be addressed through constructive, consistent engagement that reconnects the individual to God and community.

Post-Traumatic God: How the Church Cares for People Who Have Been to Hell and Back is published by church Publishing, ISBN-13: 9780819233035

Carlo Uchello is a member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, where he serves as a Lector/Chalicer and on the Altar Guild. He has previously served on the Adult Education Committee.

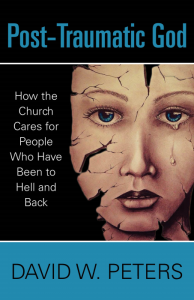

image: A shell-shocked U.S. Marine during the Tet Offensive in Hue, Vietnam, 1968. Photographer Don McCullin