Readings for the feast day of Charles Todd Quintard, Bishop of Tennessee:

Charles Todd Quintard is, at best, a complicated character in the pages of the history of the Episcopal Church, and it gets more complicated when we live in times where we are starting to question the narrative of the Confederacy and “The Lost Cause” that has long been a cultural part of the American (white) South.

For starters, although Quintard is associated with the South, he was a Northerner by birth (born in Connecticut), and attended northern schools for his first vocation, physician. He received his medical degree from New York University and additional training from Bellevue Hospital. He moved to Memphis, TN in 1851 to practice medicine because he (incorrectly) believed it to be a locale that would be free of yellow fever. Within three years, he turned away from medicine to study for Holy Orders, based on his friendship with the first bishop of Tennessee. He was ordained a deacon in 1855 and a priest in 1856.

When the Civil War broke out, Quintard’s sympathies were with the Union. Yet when Tennessee seceded from the Union, his loyalties changed, serving as chaplain and, unofficially, surgeon, for the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment. Following the war, he became the second Bishop of Tennessee, and was instrumental in the founding of the seminary at The University of the South at Sewanee.

Yet, and the same time, he also opposed plans to segregate Episcopal churches in the South. He also raised money for Hoffman Hall, an African-American seminary near the campus of Fisk University.

LIke I said, it’s complicated.

Our history in the church is to praise Quintard–after all, he helped found one of the Episcopal seminaries that still exist today. He did many praiseworthy things in his lifetime, and is historically well-thought of enough to be on our calendar of saints. Yet at the same time, in an era where we question the redeeming value of Confederate statues, and are becoming less and less enamored with giving a free pass to those who took up the cause of the white South, it’s hard to get the warm fuzzies about a man who shared a bed on encampment with Nathan Bedford Forrest and hob-knobbed with Confederate generals, even evangelizing to a few.

Were his later efforts for African-Americans in the Episcopal Church motivated by a deeper Gospel conviction? Guilt? Something else? Or were his efforts simply a more generous expression of Jim Crow? It’s hard to say. Our hope, of course, is that Quintard, at some point, saw the world differently than the typical view that existed in the antebellum South. We have evidence he might have. Yet, really, we’ll never know the reasons he made the choices he did. Those reasons may be for reasons to which we can no longer turn a blind eye. Perhaps he did as well as he could, for the times in which he lived. Perhaps he didn’t.

Bishop Charles Todd, in some ways, is a “poster child” for the struggle we now face in the 21st century when someone is on the wrong side of history in situations where we can no longer always give a free pass. He’s a reminder that the work of reconciling ourselves to one another–and, at times, to the company of saints–is ongoing work.

How do we learn to sit, with God’s help, among unpleasant truths of the past, alongside people in history who we can no longer simply laud their good works without commentary of larger, more corporate sins in which they participated?

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri as Interim Pastor at Church of the Good Shepherd and Chaplain of the Community of St. Brigid, both in Town and Country, MO.

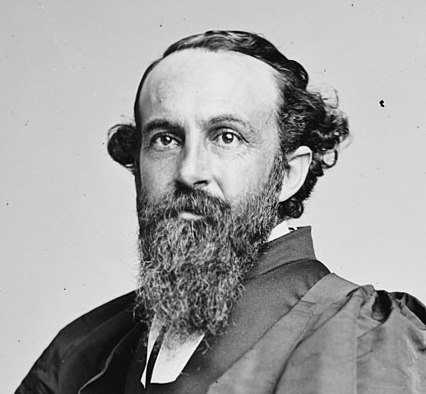

Image: By Mathew Brady – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpbh.03049. CALL NUMBER: LC-BH82- 5376 A <P&P>[P&P], Public Domain, Link