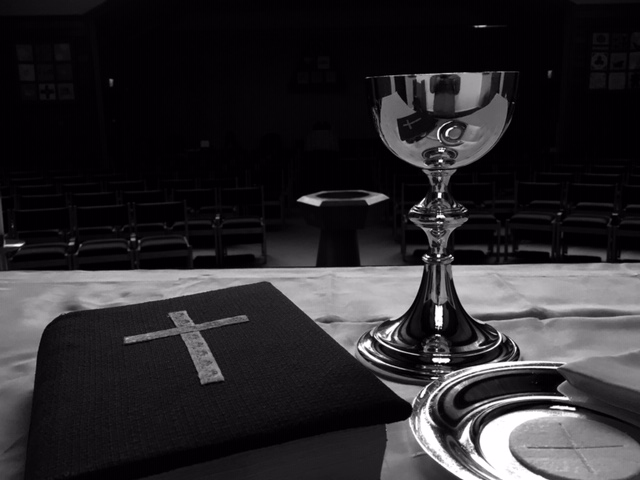

Sundays are feeling strange. In my diocese, no Chalice. And definitely no touching. The first week of the Plague at the Peace we wandered around like BBs in a boxcar, bowing, smiling sheepishly, uncomfortable. Mine is a small congregation so we all know each other, and normally it is hugs all around, with nobody missed. And then the Eucharist, with no Cup. Not for anybody. No matter what rank or order, we are all brothers and sisters. And no hand holding. Purell replacing incense. And the sadness flowed over us. But a different closeness. Yes, it was a lesson. A way to remember what we do and why we do it made clear in the absence. A new way of opening up. An unexpected Lenten fast. Letting go. But not letting go of God, because God wouldn’t let us let go.

Today’s Gospel, Mark 5:21-43, is a lot about touching. And a lot about uncleanliness transmitted by touching the unclean. Blood. The dead. But the world is full of hemorrhaging and death. Two stories intertwined. Two women, one unclean for 12 years, one only 12 years old and dead. And Jesus had just come on one of his frequent boat trips from the other side, the Gentile side, to heal a demoniac who lived in the caves where the dead were buried. Unclean.

In brief, Jesus is approached by Jairus who begs Jesus to heal his dying daughter. Jesus goes with him until he is stopped by the crowd begging for his help. A woman who has been hemorrhaging for twelve years, an unclean woman, who can’t carry a child, who can’t be touched, who is made infertile and socially dead, dares, and pushes through to touch his garment. And is healed. Jesus feels the flow of energy and turns, demanding to know who touched him. His disciples scoff at the notion that she can be identified in the mob, but she is. And Jesus affirms her healing, citing her faith. In the meanwhile the child has died. People from Jairus’ household come to tell Jesus not to bother as it is too late, and she is dead. Unclean. But Jesus pushes on accompanied only by three from his inner circle. Ritual mourning has already begun, but Jesus asks why the commotion when she is only sleeping (sometimes a euphemism for death). He is mocked. He enters the house and, speaking in the common language of Aramaic, he takes her hand and tells her to get up. He finally tells her parents to get her something to eat. First, that is a practical suggestion, but moreover it links Jesus to nourishment, ultimately the nourishment of the Eucharist. And finally it will be proof she is actually alive, and not a ghost. Zombies don’t eat.

Much analysis has been done on the relation between these two daughters of God, both now fully alive, cleansed, rejoined with the human family, both now able to be bearers of life. But there is another way to see these two healings, plus the one of the Gerasene demoniac. Not as healings at all, which are what in John are called “signs,” but as forgiveness for sin. We mocked those superstitious people of old thinking that God was punishing the ill or dying for some secret sin. But what is a sin? Turning from being fully alive in God. And who is without sin? Well, Jesus, we suppose. Any others? No? A very short list! There is personal sin and social sin. There is community sin and the interactions amongst all those creatures created by God through evolution. Is the coronavirus latching on to the sinful? Well, only that we are all sinners, incomplete, imperfect, and we are interacting with a complex and dangerous world. One in which we don’t have much control. And that is how these people in the Scriptural narrative are sinners. But Jesus is not just coming with a spiritual band aide, but actually cleansing them, making them alive, complete. They are not merely healed. They are saved. Yes, by the faith of Jairus and the unnamed woman, they are saved, but it is only when the woman is called out and she tells him the truth that she is truly forgiven. It is that honesty, that relationship with God that opens up the flow of power, of love that heals, that saves.

So here we are. The cup, which the reformers risked their very lives to bring back to the people of Christ, snatched away from us. And touching? We were already on our way with that. Safety rules, you know. Can’t hug, or pat a back. It might lead to outright adultery. Can’t trust people. And we mock a culture that wraps up its women in burkas and covers their faces. How different have we become? Even laying on of hands in healing has to be done at the distance of a painted halo. And so human touch, too, is being removed. A Body. But from a safe distance. Like the safe distance that we still hold ourselves from the sick, the dying. Looks a lot like sin, doesn’t it? And how does it feel to have the cup denied, the hug denied. And in many places the celebration of the Eucharist has been totally banned. This is frightening, every bit as frightening as the thought of a pandemic. This is a Lent when fasting and abstinence is not just something we do to prove we are in charge. This is a Lent where fasting and abstinence are thrust on us, and we are definitely not in charge.

What can we learn from this? What gift can come from this time of uncertainty and fear? Like the woman cured of the flow of blood, and the irony is that it is through him whose very blood saves us all, we, too, need to turn to him and confess that we were afraid, embarrassed, felt unworthy to break through that purity taboo and ask for help. That is faith. But not to set out the items we want fixed and the timetable. Just to confess fear and being lost and confused is enough. And living with the uncertainty. That is the faith that heals us.

We are being tested. That isn’t a bad thing. We can come through this with a new awareness of what we do and what it means. And what loss means. We can learn to accept a dangerous world with the essential knowledge that God loves us, and that Jesus has already saved us. It is finished. We can come to a new understanding of sin, those we commit and those thrust on us. And that most of our sin is not being honest with God. Be courageous, because God already knows. We can struggle with new and wonderful medical science, and we should, but we also should not forget that we don’t actually control much. New strains of COVID will evolve, as will Ebola and all the old terrible enemies. And we will engage in wars and kill innocent children, and that is all our sin. But we must remember that Jesus came and died for us. Our Lent has been given to us this year. But so has Salvation. We must remember that Jesus rose again, and if we are still under quarantine through Eastertide, Jesus still died for us and rose again. And Jesus will continue to touch us, forgive us, even if we must abstain for a while. What are we giving up for Lent? A lot. And nothing.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is at Good Shepherd Episcopal Church, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.