The Memphis Commercial Appeal announces the April 4 unveiling of a new historical marker commemorating Nathan Bedford Forrest in a story by columnist David Waters:

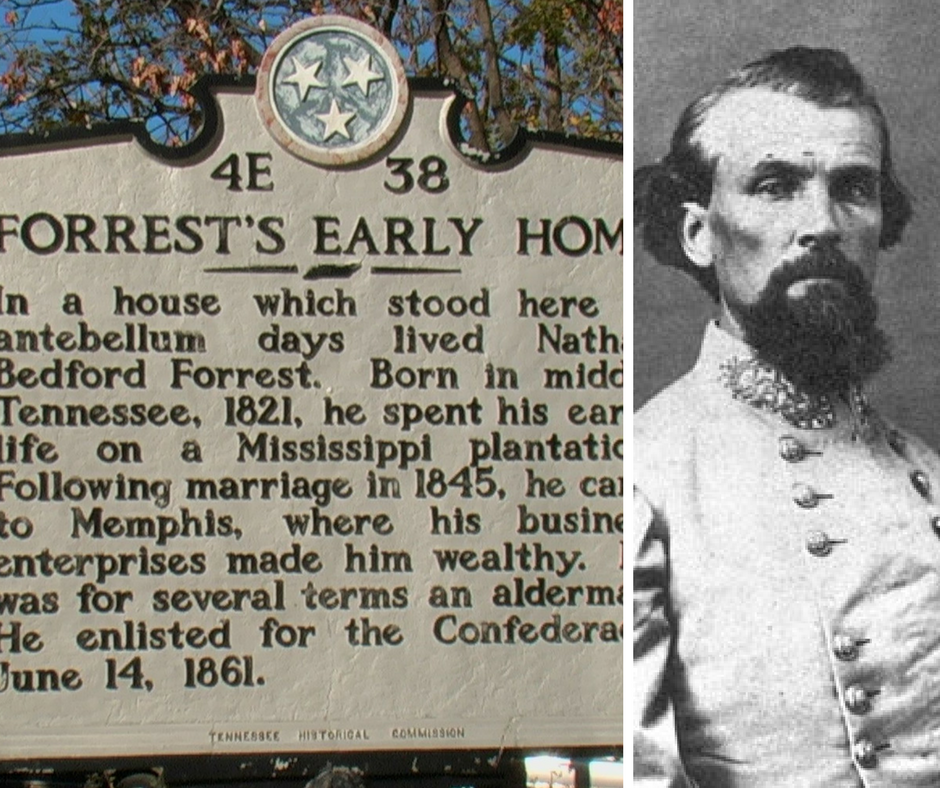

It will be erected near the corner of Adams Avenue and B.B. King Boulevard, on the church’s property and near a 1955 historical marker for “Forrest’s Early Home.”

The 1955 marker notes that Forrest’s “business enterprises made him wealthy.” It fails to note that Forrest’s primary business enterprise, operated on that site, was slave trading.

The three organizations sponsoring the new sign are Rhodes College, the National Park Service and Calvary Episcopal Church in Memphis.

Timothy Huebner was involved in his roles as a history professor at Rhodes College and a parishioner at Calvary. His students assisted with the writing of the text; professors at the University of Memphis were part of the group who reviewed the text.

The new marker will note that “From 1854 to 1860, Nathan Bedford Forrest operated a profitable slave trading business at this site.” It also will note that “Forrest uniquely engaged in the buying and selling of Africans illegally smuggled into the United States, in violation of an 1808 congressional ban.”

From WREG News Channel 3:

The dedication of the marker is supported by grants from the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area and the National Park Service.

There are currently at least seven historic markers across the city which mention the Confederate general.

Forrest was one of nine slave traders in Memphis in the 19th century, and was later a general in the Confederate army and the Ku Klux Klan’s first Grand Wizard. He bought a lot on Adams in 1854, two years after he moved to Memphis, and made it a major slave trading site in the city.

In a December 2017 column for the Commercial Appeal, Huebner wrote,

Horatio Eden, who as a child was sold from Forrest’s yard, later remembered the place. It was “a kind of square stockade of high boards with two room Negro houses around … We were all kept in these rooms but when an auction was held or buyers came, we were brought out and paraded two or three around a circular brick walk in the center of the stockade. The buyers would stand nearby and inspect us as we went by, stop us, and examine us.”

Although his business probably resembled those of other traders in town, Forrest appeared unique in his willingness to engage in the smuggling of Africans into the United States, in violation of federal law. Several sources confirm that in 1859 Forrest sold seven Africans “direct from the Congo” at his yard.

Forrest and others made a lot of money in the slave trade, and they apparently did no damage to their reputations at the time. Although popular lore has held that society looked down upon antebellum human trafficking, recent historical scholarship argues the opposite — that traders were well-connected businessmen rather than social pariahs. In 1858, in fact, Forrest became a city alderman.

Forrest has been the subject of recent protest and civil actions, as his statue was one of three removed by the city – his was previous located on his and his wife’s grave in Health Sciences Park. More from the Commercial Appeal:

[Mayor Jim] Strickland: ‘No place’ for hate groups in Memphis; city expects to sue state over Confederate monuments (August 14, 2017)

Nathan Bedford Forrest statue in Memphis draws protesters overnight (August 15, 2017)

Forrest family, Sons of Confederate Veterans sue over takedown of Memphis statues (January 12, 2018)