by Michael Fitzpatrick

Many of my fellow Anglicans do not seem as excited as I am about the upcoming Lambeth Conference. Much of the lack of enthusiasm seems to hinge on affirming or repenting of a single resolution from the 1998 gathering (Resolution 1.10) regarding the nature of marriage. The past few years have afforded me the privilege of reading some of the many great resolutions over the years at Lambeth, including what used to be the litmus of Anglican identity, the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral- Resolution 11 from the 1888 convocation – which affirms our unity in scripture, creed, sacrament and episcopacy. Given such a great treasure of resolutions, why does our ability to fellowship together as Anglicans hang on the singular topic of marriage (marriage is deeply important for Anglicans, but it is not the Gospel, and it is not the Lord’s Supper or Baptism)?

If we can share and affirm many other resolutions from Lambeth Conferences past, does this not provide us a wide heritage in common? In his opening address, then-Archbishop Robert Runcie spoke on the question of Anglican unity at the 1988 gathering, proclaiming, “We are not here to avoid conflict but to redeem it…” Conflict, then, far from being an unmitigated evil, is, if handled creatively, an essential part of our understanding of the processes whereby the Church speaks with a living voice today.” Disagreements between Christians are not reasons to refuse to gather together, but precisely reasons to attend, so that through our tensions and disagreements we can better discern the Spirit’s work in our branch of the Church.

Resolution 22 from the 1988 Lambeth conference seems like a much better choice to serve as a hinge uniting bishops attending the upcoming conference. In this resolution, the ‘88 conference:

(a) Recognizes that culture is the context in which people find their identity, (b) affirms that God’s love extends to people of every culture and that the Gospel judges every culture according to the Gospel’s own criteria of truth, challenging some aspects of culture while endorsing and transforming others for the benefit of the Church and society, and (c) urges the Church everywhere to work at expressing the unchanging Gospel of Christ in words, actions, names, customs, liturgies, which communicate relevantly in each contemporary society.

This resolution places the focus back where it should be, on the Gospel and on its relationship to the world. Both liberal and conservative churches can concur with this resolution, despite applying it differently. What matters is not that we do everything the same way, but that we work from the same foundation. Resolution 22 affirms that the Gospel is unchanging, and that the Gospel judges the culture, while simultaneously affirming that God’s love is for everyone and that the Gospel must be clothed in ways that communicate to contemporary society. Resolution 22 provides much common ground for dialogue about how our faith lives out the Gospel.

Out of the hundreds of resolutions that have emerged from the Lambeth Conferences, there are only a tiny number that are in dispute within the Communion, and that means we do have a tremendous foundation for unity and dialogue. It’s this tremendous foundation that has meant so much to me. I grew up in a very conservative Christian community with theology nearly inexplicable to me, whether on evolution or the end times or social morality. When I discovered that Anglicans had found a better way to do theology even before I was born, it was a breath of fresh air! This better way is still the Anglican way.

Sadly, one would hardly know this from recent Gafcon communiques. The G19 gathering in Dubai at the end of February asserts that “Gafcon is a movement for the reform and renewal of the Anglican Communion by faithful Anglicans who find their beloved Communion has been devastated by those preaching and practicing another gospel (Gal 1:6-7).” This accusation of “another gospel” is echoed in the March 2019 outgoing Chairman’s letter in which Archbishop Nicholas Okoh writes that the attendees of the G19 “feel the pain of betrayal when the gospel they love and serve in lives of costly discipleship is confused, undermined and denied in other parts of the Communion.” The accusation of a false gospel being preached is the most serious accusation of all.

This accusation of a false gospel gestures toward Galatians 1. When we look at Galatians 1, and the context surrounding vv. 6-7, we discover that the “other gospel” being denounced by St. Paul is the “gospel” of the Judaizers, those Christians who sought to impose circumcision and other OT laws as conditions for accepting Jesus Christ as Lord (cf. Gal. 2.3-5 and Gal. 5.2-6). A little reflection on the marriage debate suggests, however, that requiring believers to accept a particular view on marriage in order to follow Christ comes closer to the behavior of the Judaizers condemned by St Paul than the behavior of provinces which have expanded their understanding of marriage. The doctrine of marriage has the appearance of becoming a new circumcision.

This is the case even if the traditional understanding of marriage is true. Even if God intends marriage to be only between a man and a woman, nowhere in scripture or creed is acceptance of this doctrine a condition for believing the true Gospel of Christ. To make Lambeth 1.10, or any statement that is not itself about the Gospel, a condition of someone confessing Jesus as Christ and Lord, seems to be what St. Paul condemns in Galatians.

My prayer is that Anglicans will resist proposals that the upcoming Lambeth conference reaffirm or reject Lambeth 1998 Resolution 1.10. This would both exacerbate the Judaizing problem I’ve described and further distance us from the real work that needs to be done. Instead, Lambeth should have one simple aim: a shared discussion and examination of what the Gospel is. If Gafcon leaders like Archbishop Kwashi are so confident that “we’re seeing some from within the church . . . teaching disobedience to the word of God, violating the very essence for which Jesus came into the world, died and was raised again,” then I invite these leaders, especially the bishops of Nigeria, Uganda, and Rwanda, to attend the Lambeth 2020 so as to demonstrate before all the bishops the differences in the gospels being preached.

Let all the bishops of the Anglican Communion come together to debate and discuss openly what the Gospel is, and what it affirms. If we undertake such work at Lambeth 2020, we will achieve greater clarity on what exactly it is that various provinces think the Gospel is about, and I suspect we will find great unity and shared conviction on that front. This would settle claims about false gospels, and create a shared resource, hopefully a resolution, about what the Gospel is and how it is practiced within the Anglican tradition. By setting forth and resolving a shared conception of what the Gospel is, a much better conversation in the Communion in light of the Gospel becomes possible for discussing marriage or any issue facing Anglicans today.

For me personally, the Anglican Communion is a visible image of what I always dreamed the Body of Christ looking like in its global form. We are a passionate worldwide network of communities united by a common tradition that exemplifies a reasonable form of Christianity, one that is passionate about the Gospel of Jesus, the Gospel that both saves people from their sins and brings the hope of grace to the least of those among us. Anglicans constantly come together to serve churches facing persecution, families suffering from injustice, and communities ravaged by natural disaster. I am so grateful to have finally found my way into this marvelous family. Please, let us join our hands to hold it together in the name of Christ.

Michael Fitzpatrick is a doctoral candidate in Philosophy at Stanford University. He serves as the student president for the Episcopal-Lutheran Campus Ministry at Stanford, and teaches topics on liturgy, theology and the Bible at his local parish of St. Mark’s in Palo Alto, CA.

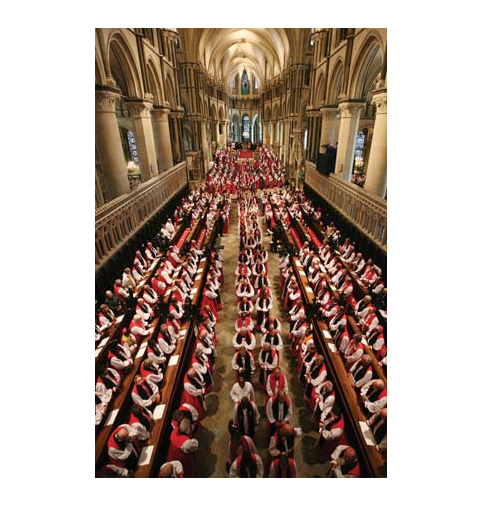

image: Lambeth gathering, 2008