Daily Office Readings for the feast of James Theodore Holly, March 13, 2020:

The beginnings of James Theodore Holly’s life are a distinctly inauspicious chapter in the life of the man who would become the first bishop of what we know as the Episcopal Diocese of Haiti.

Holly was born in Washington DC in 1829, the son of freed slaves, and moved to New York City when he was 14.. At that time, the path to upward mobility for most free African-Americans was in the trades. Holly’s father was no exception to that rule–he was a shoemaker, and taught young James the trade. By the time James was 21, he and his brother ran a bootmaking shop. Although he was reared as a Roman Catholic, by the following year he had crossed the Tiber and had joined the Episcopal Church. He had departed from the Roman Catholics over their refusal to locally ordain black priests.

He had also begun to be involved in the abolitionist movement and had met and been influenced by Frederick Douglass. Not long after he married his wife Charlotte in 1851, he moved to Windsor, Ontario and became the associate editor of a weekly abolitionist newspaper called The Voice of the Fugitive. He and his family moved to Buffalo, NY in 1854, and he, like many other African-Americans, had begun to turn an eye towards Haiti. The Haitians had kicked out their colonial rulers, the French, in 1804 and the developing society there was of keen interest to African-Americans. The American Colonization Society had already helped several families emigrate to Haiti. Was it possible to emigrate there and start anew, in a land without Jim Crow laws?

As his involvement in this work continued, Holly began to feel the call to Holy Orders. He was ordained a deacon in 1855 and a priest in 1866. Around that time he was one of the co-founders of The Protestant Episcopal Society for Promoting the Extension of the Church Among Colored People–you and I would know them as the Union of Black Episcopalians. He was clearly becoming more deeply involved in the emigration movement, and in 1861 he led 110 African-Americans to settle in Haiti.

Unfortunately, they were not prepared for the harsh conditions in Haiti and that yellow fever was endemic there. Many died of malaria, including his wife, a son, a daughter, his mother, and one of his sons to the disease. Even that did not deter him, and he stayed with his two remaining sons. By 1874 he had been consecrated bishop–the first African-American bishop in the Episcopal Church. (The honor of being the first in the United States itself would go to Henry Delany.) Holly would remain Bishop of Haiti until his death. By that time, he had long remarried and had nine more children.

Bishop Holly’s life is one of persistent faithfulness, even in the midst of infectious disease. What lessons might we learn from him as we face an infectious disease crisis today?

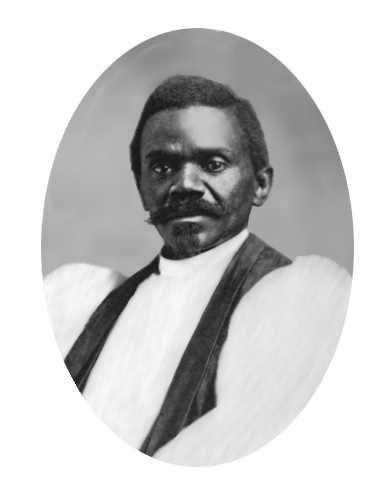

Image: Caption: James Theodore Holley, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri , as the Interim Pastor at Christ Episcopal Church, Rolla, MO.