We have just read the entry into Jerusalem by a different kind of king, one on a donkey colt, in accordance with prophecy, lauded by his followers and the general crowd. And then Mark’s Gospel says a curious thing. “And he entered Jerusalem, and went into the temple; and when he had looked round at everything, as it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the twelve. (Mk 11:11).” Leaving town before the gates of a walled city were locked for the night, and Jerusalem was a walled city, makes sense. Better to find someplace to eat and sleep with friends outside the city, and Jesus had friends in Bethany. But what I flashed on was, “God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the sixth day (Gen 1:31). . . By the seventh day God had finished the work he had been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. Then God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done (Gen 2:2-3).” If the entrance into Jerusalem was on a Sunday, the day after the Sabbath and the day we celebrate as the beginning of the week, the Resurrection day, was Jesus looking around and saying, “This is not very good”?

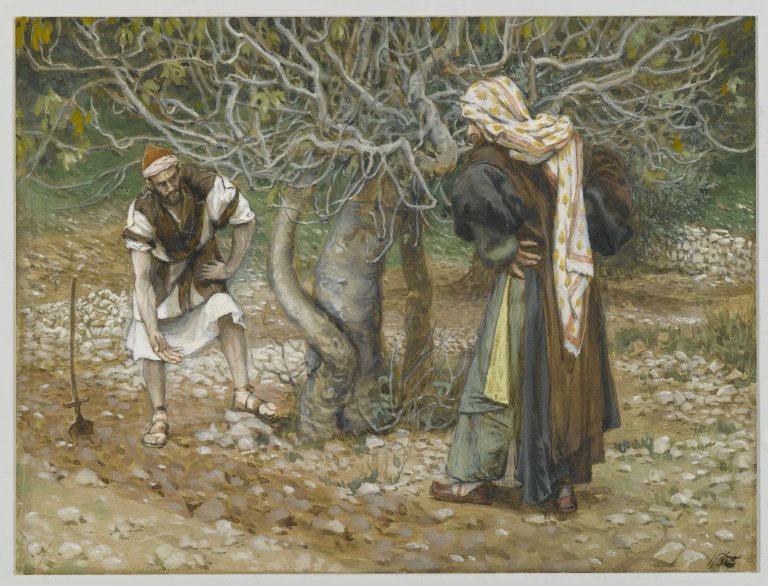

Jesus was hungry. For figs? For the Kingdom of his Father? And so we have the poor fig tree, the innocent that died for showy leaves but no fruit out of season. The showy temple, but no fruit, and now out of season, even days before the Passover, the celebration of the Jewish liberation, of the promises made to them by God through Moses. Was not the fig tree a metaphor for the Temple? For Israel (Hos 9:10)? And Jesus, the new Moses, seeing sterility and bringing the promise of new fruit, a new liberation, was Jesus, the living Temple, also the fig tree? And then Jesus returns to Jerusalem to have a public melt down that begs for the power elite in the Temple to react. Again, it is sad for the innocent merchants just plying what they must have considered a holy trade, providing appropriate coins to pay temple tax and unblemished animals for sacrifice. For a shepherd, finding an appropriate lamb isn’t a problem, but these are urban people who perhaps keep a few chickens or no livestock at all. And a whole industry arose to meet the needs for sacrifice and ritual purification, especially for the High Holy Days. A house of prayer for all people, and the Greek does say τοῖς ἔθνεσιν, toi ethnisin, all ethnicities. All people, and in Mark’s church this was already true. The Temple in Jerusalem, dedicated to the Holy One of Israel, has become a den of thieves, a source of revenue for the Temple and its priestly class. Once again Jesus goes out of the city, out of Jerusalem.

And here again is the fig tree, now dead, and when Peter points out this wonder, Jesus uses this moment for another lesson. We of little faith. We don’t expect curses to work, and probably don’t expect prayers and blessings to work. I do not doubt that for God all things are possible. But we don’t really expect mountains to move if we strain hard enough at our faith. Jesus does stipulate that we aren’t doing super magic. We are asking God to make things happen for us because we asked, but sometimes it feels more like a demand or even blackmail. I’ll do this for you if you do this for me. Unfortunately this teaching, which is really about faith, has turned into magical thinking. We are casting our spells but using the name of God for agency. That isn’t very relational with our Abba in Heaven. And we do ask for impossible things. Aunt Tilly’s stage four lung cancer probably isn’t going away, not after a lifetime of chain smoking. Of course, miracles do happen, but it isn’t a gimme. But Jesus also said to keep our prayers simple. And to love our enemies, not hate them. We know he goes alone to pray. We know he speaks of his signs as bringing glory to his Father. We know about praise and thanksgiving, about praying for mercy in penance, about interceding for others and for ourselves. About offering ourselves to God in prayer, the true oblation that our God desires. So what is Jesus teaching here? With enough faith and persistence can we demand miracles? I think what all these teachings have in common is the command to keep talking to God our Father. How this relates to cleansing the Temple is that the children of God at that time had a wall between themselves and their God. And being heard costs money. While it was true that the priestly sacrifices were for the people, the rich and powerful had turned the Temple into a business which was benefiting them. But Jesus didn’t just come to reform the Temple, but create a new covenant, one for all people, and one which would exclude no one. And if he wanted to call attention to himself, to poke at the Temple elite, smashing up their source of revenue was a good way to do it.

Are we a generation of little faith? Thoughts and prayers have come into some disrepute these days. Sadly, the call for social justice at the expense of prayer has only cut more deeply into the faith of the Church. Why call on God at all if we are empowered by our free will to take action, whatever that action may be? And yet what Jesus came for was to bring us closer to God through his own personal love and sacrifice as Son of Man and the gift of the Spirit as Son of God who could guide us in prayer. Not for the miracle du jour, but for each of us to find our own deepest intimacy with God, our deepest desire. And as a Body to sustain each other as we share that Spirit and we strive to embrace the God who loves us.

Have we created our own Temple? I think to some extent we have. And the cleansing of the Temple is always a warning for us to be mindful that we serve God by serving one another, not by claiming privilege of station for our service. People need some level of social organization. Show me a species that doesn’t, and with higher degrees of self awareness and sentience, and we aren’t the only of God’s creatures that have it, we have that need in abundance. We need our temples, and we need our priests and pastors, our teachers, our mentors, our scholars. But we need them to guide prayer, not own it. We need our faith communities and our personal practice of our faith to be ever reminded that God is with us, loves us, and will grant us whatever good things we need. But we are also part of the Kingdom, and God’s plan takes precedence over our personal very human personal requests. And so in God’s plan a perfectly innocent fig tree dies as a demonstration of the Temple’s lack of nourishment, and as a surrogate for the Christ who will also die so that he can feed us forever.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is a parishioner at All Souls Parish, Episcopal, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.