The notebook pages were scribbled somewhere between 1604 and 1608, the deadline year for six teams of collaborative translators tasked with translated the King James Bible, which was first published in 1611. The New York Times reports on the discovery and what it illuminates about the creation of the King James:

David Norton, an emeritus professor at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and the author of several books about the King James Bible, called it “a major discovery” — if not quite equal to finding a draft of one of Shakespeare’s plays, “getting on up there.”

The discovery brings to four the number of known drafts:

While some records of the committee that supervised the overall translation survive, only three manuscripts of the text itself have been known to exist until now. The Bodleian Library at Oxford owns nearly complete drafts of the Old Testament and the Gospels, in the form of corrected pages of the Bishops’ Bible, a 16th-century translation that the King James teams used as a base text. Lambeth Palace Library in London has a partial draft of the New Testament epistles.

Jeffrey Alan Miller, an assistant professor of English at New Jersey’s Montclair State University, was in Cambridge researching Samuel Ward, one of the King James translators and a master of Sidney Sussex School there, when he found the draft.

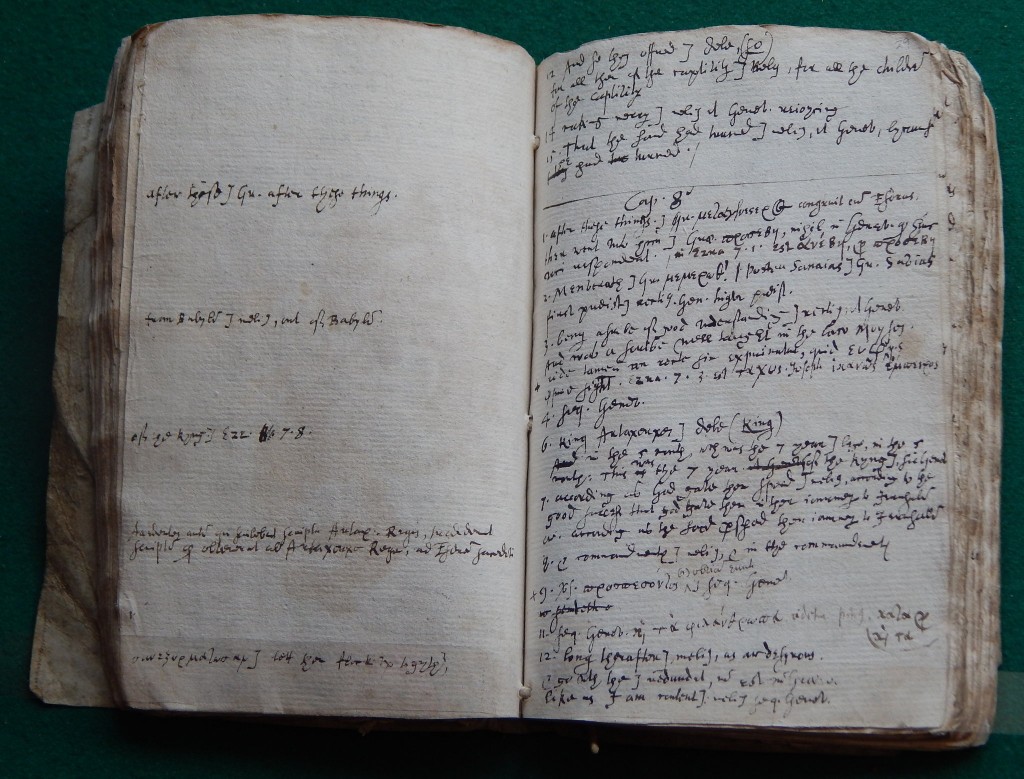

The notebook had been cataloged in the 1980s as a “verse-by-verse biblical commentary” with “Greek word studies, and some Hebrew notes.” But as Professor Miller tried to puzzle out which passages of the Bible it concerned, he realized what it was: a draft of parts of the King James Version of the Apocrypha, a disputed section of the Bible that is left out of many editions, particularly in the United States.

The nature of the draft shed light on the process of the King James translations:

Unlike the other surviving drafts, which scholars date to later parts of the process, it shows an individual translator’s initial puzzling over aspects of the Greek text of the Apocrypha, indicating the reasoning behind his translation choices, with reference to Hebrew and Latin as well.

“You can actually see the way Greek, Latin and Hebrew are all feeding into what will become the most widely read work of English literature of all time,” Professor Miller said. “It gets you so close to the thought process, it’s incredible.”

The draft, he argues, also complicates one long-cherished aspect of the “mythos,” as he put it, surrounding the King James: that it was a collaborative project through and through.

The companies were charged with doing their work as a group, rather than subdividing it by assigning individual books to individual translators, as was the case with the Bishops’ Bible. But the Ward notebook, Professor Miller said, suggests “beyond a reasonable doubt” that at least some of the companies ignored the instructions and divided up the work among individuals, at least initially.

Miller announced the discovery in the Times Literary Supplement.