I live my life in Christ in the everyday world, but I live a life informed by a monastic rule set down in the fourth century CE. Where did it come from and why is it important to me?

We live in the Body of Christ, in community. The first Christians lived in and by community. The letters of Paul and the Apostles are all addressed to communities. But some are called to live in the solitude of God. We know from Philo, a Hellenized Jewish theologian, and a contemporary of Jesus, that there were Jewish hermits as early as the First Centuries BCE and CE. The first notable Christian ascetic was St. Antony the Great (c 251-356 CE) whose feast we celebrate on January 17th. But even he gathered disciples around him both men and women who lived in a loose community.

The next development of monasticism came when an ex-Roman soldier, Pachomius (242-348 CE), was converted and took up the ascetic life near St. Anthony’s hermitage. Hearing the word of God, Pachomius took over an abandoned village, Tabennesi, Egypt, and founded a community based on koinonia, a word that means community (Acts 2:42), fellowship, as in the Trinity (1 John 1:3), even the Eucharist (1 Cor 10:16).

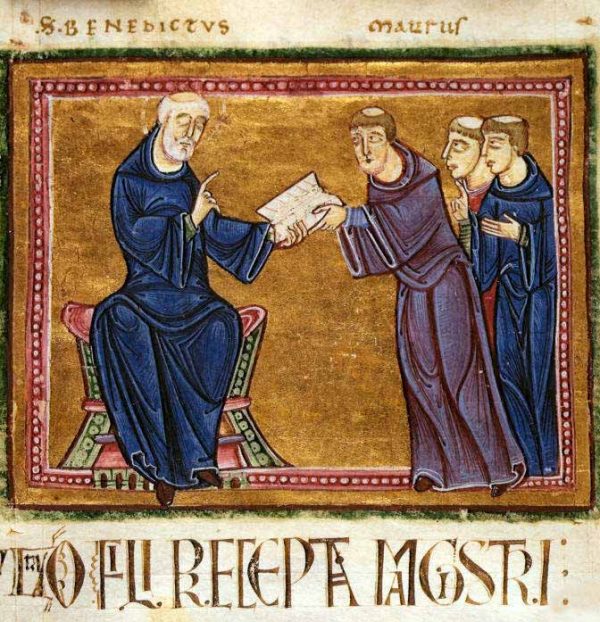

Skipping a number of important saints and communities, probably the most influential to us in the West and in contemporary spiritual life is St. Benedict (c 480-543 CE). While his Rule to order and organize his community isn’t the first by far, it has become the touchstone of living a prayerful and reflective life, both in cloistered communities and in the workaday world.

In graduate school I studied religious life and thought I knew the Rule of Benedict, but it was my spiritual director who taught me its elegant simplicity and the path to living in Christ through that Rule. A trinity of words: Stability, obedience, conversion.

Stability means staying put, learning to live in Christ with that sometimes messy community. It is the first discipline of an ordered life. Benedict’s rule of stability was aimed at monks who wandered looking for greener pastures (the gyrovague), not recognizing that God was always within them. Although I have tried to live a life of prayer and moderate asceticism, I have had the (sinful) tendency to wander off on my own, following my own will, especially in times of crisis, and, in this very secular and tempting world, to leave God and the Church. When I say that God forgives and is merciful, I can only witness that when I returned, confessed, and truly repented, I felt the rushing back of my Heavenly Father as he came to greet his feral and prodigal daughter so powerfully that it left me breathless and shaken, grateful, and forgiven. Running away is never the answer.

Obedience is tricky. A good community, a good mentor, a strong prayer life, and a base of your own self identity and worth to God are all necessary. At that point a person, especially a strong one, can gracefully yield to another’s will, or teaching, or need. At best, it goes both ways. A good stable religious or intentional Christian community works like that. A solid parish can, too, to the extent that members put themselves into it. Obedience to God is never optional.

Most monastic rules mandate long periods of silence each day. In part it is to let the Spirit speak. Mostly it keeps down gossip, discontent, and cliques. Obedience requires listening to each other, respecting each other as we honor the Christ in each other. It is an act of humility. It isn’t always easy. We humans have a better chance if we don’t talk so much. A modern example of how this can spin out of control is social media. Facebook, Twitter, and all the ways the throw our lives and biases into each other’s (virtual) faces do not bring Christ closer.

Conversion, I think, is the Spirit’s work, but the ground is tilled in that loving, but sometimes difficult, community. We can invite it by listening to those around us. And we must take in what we hear, if need be. Correction can be a blessing. Conversion in the Rule, conversatio morum, means fidelity to the monastic way of life. Conversion in the world is about life change, knowing who we are and to whom we belong. It is living a life righteous in the sight of God.

We live in a society yearning for total freedom. My path puts boundaries on that autonomy, but ones based on God’s word and love. The true freedom gained is beyond description. I always know when I have strayed when what I am doing, no matter how well intentioned, leaves me feeling uneasy, separate, wanting to disobey, hearing only my voice, to run away rather than facing the realities of koinonia. Time to turn, confess, seek God’s will, find peace.

The peace of God is not a slogan on a poster, but an inner peace that can put up with small children and many cats. Or poverty. Or death in a concentration camp. God’s peace gives stillness. Not stifled stillness, but a grace to know, as Dame Julian of Norwich said, that all will be well. And it brings the silence of a stilled mind. Not one forced into the silence of a Zen boot camp. Just quiet in the safe hand of our God, in the embrace of our Redeemer, in yielding to the Spirit.

I am not ashamed to say, “My Lord and my God,” or see God as a merciful, if sometimes strict, parent. Service and duty are deeply ingrained in me, so much so that I often have to ask if I am obedient to God’s will or my will. “Master” and even “slave” are terms I have come to term with. I use “sin” rather than psychological language because it reminds me that turning to God is the cure. And “demon” personifies the thing or behavior that gets in my way. And it is much more satisfying to deflate and kick out a demon. Language has power. When the Gospel of John calls Jesus the Logos, the Word, it rules out Jesus as just another Messianic reformer. So I use and pray hard words.

Stability, obedience, conversion mean so much to me in my growth in Christ that I would be remiss not to hold them out to you. In these quiet weeks before Lent try exploring a spiritual rule, a guide, not a straitjacket. Each of us will hear God’s will a little differently. We are a community, after all, not a robot factory, and our God loves our diversity. And when the Lord comes to you listen, obey, and worship.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is a parishioner at All Souls Parish, Episcopal, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.

Image: St. Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order Public Domain, Link