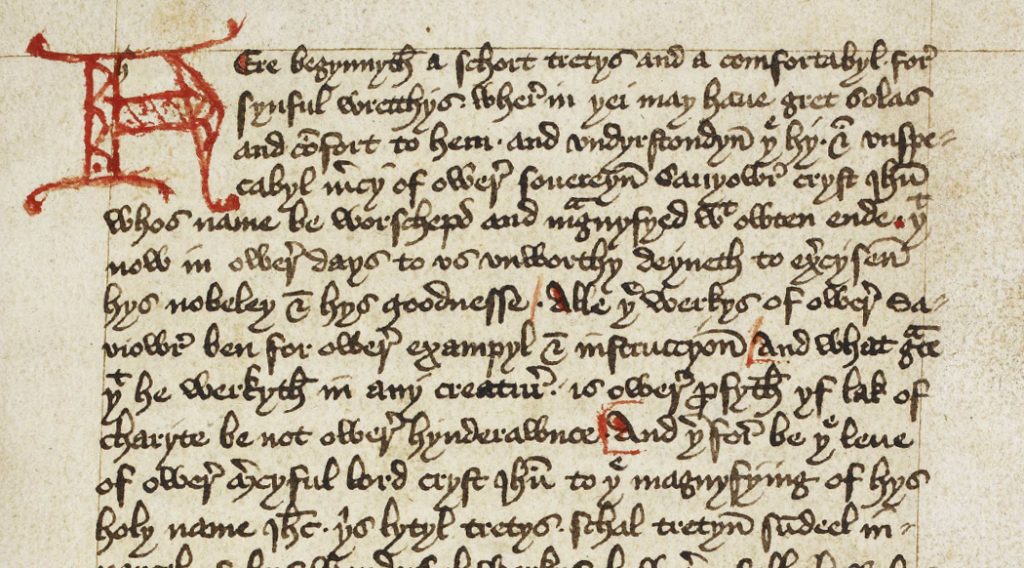

(Page from the Book of Margery Kempe, source unknown)

Readings for the feast day of Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton, and Margery Kempe, September 28, 2018:

In our Epistle today, Paul reminds us that each of us, in our flawed human bodies, is still an acceptable living sacrifice to God. Margery Kempe might be one of those folks who give us hope that God can use all of us–no matter how many quirks or oddities we might have.

Margery’s life started out pretty typical for a woman of her time. She was born Margery Burnham in (as best as we can tell) 1373, the daughter of a local magistrate in Norfolk, England. Like many girls of her time, she was not taught to read or write, yet she memorized prayers and Scripture. (Most scholars believe her accounts of her travels were dictated to a scribe.) When she was roughly twenty years old, she married John Kempe, who would later become a town official. She bore fourteen children–not particularly unusual in a time when, other than a few home remedies, birth control was unknown, and life expectancy was short. Yet it was after the birth of her first child that things started deviating from the typical life of women of that time.

Shortly after her first child was born, Margery started having visions of demons and devils telling her to turn her back on her family and her faith, even whispering to her that killing herself would be a desirable option. Suddenly, though, the visions changed. She began having visions of Christ, and envisioned herself being actively a part of his birth and crucifixion, complete with sights, sounds, and smells. She began hearing what she called a “heavenly melody” that made her weep–constantly. In fact, she was known by the locals for her habit of wandering about town weeping. For those of us with a medical background, she clearly suffered from postpartum psychosis.

Yet Margery, even in her illness, found connection with Christ, and found a reason to turn away from her suicidal demons and live, willingly suffering the negative responses of her local community for her devotion. She found herself desiring to live a celibate life, and at one point, her husband agreed on the following conditions: 1) They continue to sleep in the same bed; 2) she pay off his debts via the corn-grinding and beer-brewing businesses she operated; and 3) she cook him a fish dinner on Fridays. It is unclear whether this occurred after she bore 13 more children, or whether there were momentary lapses in the agreement…and it’s not that Margery didn’t have a lapse or two herself. She once threw herself at a man in the town where they lived, and asked if he would “consent to have her.” He clearly was not interested in the proposition, saying he’d rather “be chopped up as small as meat for the pot.”

Another outgrowth of Margery’s search for herself involved taking several pilgrimages, including one to Jerusalem. She also began to travel to seek counsel from various Christian mystics of her time, particularly Julian of Norwich, who affirmed to her that her experience was genuine. Church officials, however, were not convinced, and she was tried for heresy on numerous occasions, yet never convicted. More than once the charge of Lollardy was hurled at her. In one account, she was chased out of church by a monk yelling, “You shall be burnt, you false Lollard! Here is a cartful of thorns ready for you and a barrel to burn you with!”

All the same, her work, The Book of Margery Kempe, is very likely the first autobiography in the English language, and is a fascinating look at a very unusual, complex life. Over time, though, hagiographers tended to scrub the details of her life from her story, turning her into more of an anchoress-type figure; yet as we examine the historical record, we discover her story is far more complicated and rich.

Margery Kempe is a difficult figure to understand in our 21st century way of seeing things. For starters, it’s highly likely only a shadow of this woman would exist today. She’d have been medicated and possibly institutionalized. The sheer oddity of her life and raw wildness of her claims makes it difficult for us to comprehend that she has valuable lessons for us today. That said, she lived in a time where women were excoriated for preaching, teaching, or claiming any insight into the divine, and the only way they were allowed to express that insight was by experiencing the divine through their bodies, the experience leading to intellectual enlightenment.

What might we learn today about the process of “how we believe” and “how we doubt” through the convoluted thread of orthodox devotion that weaved through Margery Kempe’s highly unorthodox life?

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri . She presently serves as Interim Assistant Priest at two churches, Church of the Good Shepherd in Town and Country, MO, and St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Manchester, MO, as they explore a shared ministry model.