By Carlo Uchello

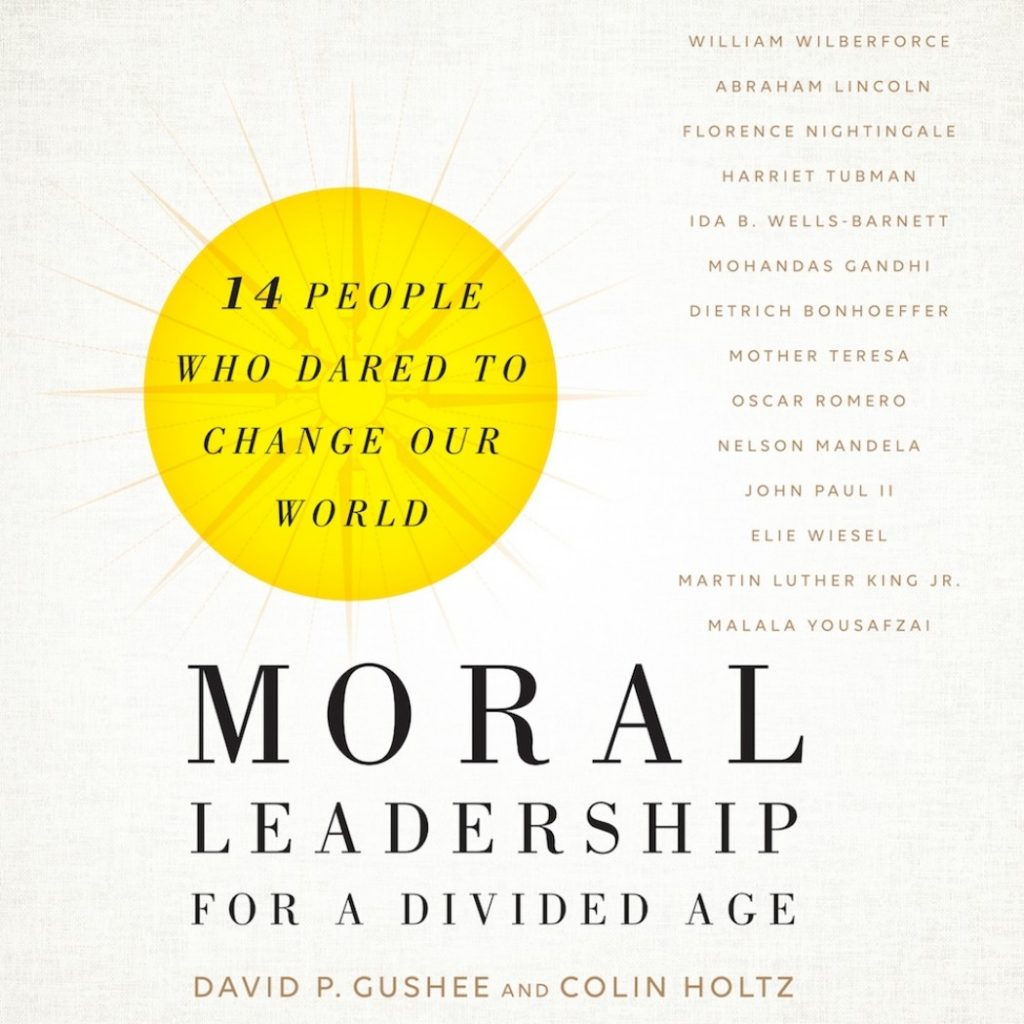

You may think that it would be easy to come up with a list of 14 people who would qualify as moral leaders, and that there would be no objections to your choices. That would seem to be the case if you only looked at the cover or the table of contents of Moral Leadership for a Divided Age, co-authored by David Gushee and Colin Holtz. After all – Lincoln, Gandhi, Mother Teresa (and others) – who could object, right?

But when you give it some more thought, you might realize that including someone such as Thomas Jefferson would be controversial, at least for some readers. In our current age of historical reevaluation where the actions of the past are assessed in the light of today’s morals, having owned slaves would automatically disqualify someone from a list of moral exemplars, irrespective of their many positive accomplishments. As another example, the reputation of Christopher Columbus clearly took a big hit right around the time we thought we would be celebrating the 500th anniversary of his landing in the New World.

And so as you begin to read the short biographies of the 14 men and women who were selected for this book, you soon discover, or perhaps re-discover, that in their own lifetimes, every one of them was disliked or even hated by a large number of people. In many cases, that antipathy continues to this day. You might very well conclude that it can be hard to make a list of moral leaders without receiving some objections. And the objections would be about some of the people who were omitted as well as those who were included.

Each of the 14 profiles in the book is prefaced with a chronology of the major events in the subject’s life and times, and each chapter concludes with leadership lessons, discussion questions, and suggestions for further reading for any reader who may be looking for more than the 20 or so pages that are provided here. It isn’t immediately clear why the authors chose to include leadership lessons and discussion questions for each the 14 profiles, but at first glance they appear to be well-suited for classroom use. But while the profiles are short and therefore provide something of a superficial review of the subjects’ lives, a pattern appears to emerge, and we start to discern the authors’ intentions. We begin to see that each of these persons faced challenges – in some cases, seemingly insurmountable ones – and yet found the courage and will to persist.

Tellingly, more than a few of the persons profiled met violent deaths or suffered grievous harm. And while we learn that each of them had character flaws or were blind to some of their own misdeeds or prejudices, we begin to see what the authors intended for us to take away from their book. Chiefly, we see that imperfect people can accomplish great things, so we should neither expect nor demand perfection from our leaders or from ourselves. Another clear lesson is that leaders are made, not born and leadership is a skill that can be developed and improved over time.

While some leaders know the general direction their lives will take from an early age, that is not a reliable predictor as to whether they will become a great leader. Others may be strong leaders well before they have had a chance to develop and espouse their moral authority.

We can easily fall into hero worship if we are blind to the moral failings of those whom we admire – and no moral leader is ever morally perfect, even the ones we may admire most. But if we expect or assume moral perfection in our leaders, one day we will be disappointed. So, too, is expecting moral perfection in ourselves. While the situations we find ourselves in may provide an opportunity to act with moral courage, the ability to act with moral authority can also be impeded by the situations in which we find ourselves. But whatever our situation, we have the opportunity and imperative to act with integrity when we encounter injustice.

Personal transformation is a recurring theme through many of the profiles in this book. To cite one example, Oscar Romero spent most of his early years as a priest who defended the traditional view that priests should not get involved in politics. He even wrote articles attacking priests in El Salvador who spoke out against the repressive government, espoused Marxist views, and preached liberation theology. It was only after he was appointed bishop of Santiago de Mario and saw the desperation of the poor that he began to understand why some priests railed against the excesses of the ruling class and the government. When he was appointed archbishop of San Salvador in 1977 ahead of another bishop who was thought to be next in line, it was largely because Rome felt that Romero would hold the line against those trouble-making priests, even though priests were frequently the target of government troops. It was only a few weeks after his installation as archbishop when one of Romero’s friends, a fellow priest, and two of his companions were murdered by government troops. Oscar Romero was only a few months short of his 60th birthday when he began his crusade against the government, and within three short years he was assassinated by government troops while saying Mass.

The story of Florence Nightingale, however, suggests that a person’s moral compass may be set in place at a much earlier age than we sometimes credit. She was raised in a privileged Victorian family but travelled extensively as a child where she saw poverty and systemic injustice. By the age of six she had received what she believed to be a calling to become a nurse. At no less than four different times in her life, she received what she believed to be callings directly from God – to become a nurse, to travel to Crimea, to never marry, and to care for the poor. She once said, “My sympathies are with ignorance and poverty,” and she let no one stand in her way of accomplishing what she set out to do – namely, to overhaul the medical profession not only at the battlefield but in every hospital and clinic in England. She was also criticized in her day for sins both of commission and omission, though to be fair, it is obvious that she pushed herself at least as hard as she pushed others. Her work led to many needed reforms in medicine which continue to benefit us today, but she still has her critics and nay-sayers.

All of us like to think that moral leadership is important, and there are moral leaders whom we admire more than others, even if we don’t often think about it in that way. When we do think about it, we may not always agree on who the true moral exemplars are, or we be uncomfortable with the methods they used to effect change. Or maybe we view them differently as we weigh some of their moral failings and consider that while they may have been great leaders, they fall short as true role models.

The leadership lessons that are provided at the end of each short biography are a lesson in themselves. Which personality traits or personal behaviors might have been important for Harriet Tubman or Dietrich Bonhoeffer might not have been especially relevant to Elie Wiesel or John Paul II. But there are some common experiences or attributes that emerge as central to almost all of those who are profiled, such as a childhood tragedy, personal imperfections, and the roles that education, family, and religion played in their lives. But in every case as well, their decisions and actions cost them dearly. Moral leadership has never been about personal glory.

The authors state that “leaders unite followers around a common goal,” but that definition doesn’t go far enough, as it ignores the necessity of principled and moral authority. To be a moral leader, you must have a specific goal or vision, coupled with high principles, and be engaged in pursuit of justice where injustice is the norm. The authors make the case that we need to watch for three traits of a leader before we can make the case that their actions are worth following. Those traits are moral impact, moral character, and moral purpose. Has the leader personally invested themselves into a noble cause? Can we admire the character of the leader – that is, have we concluded that in spite of any flaws they may have, their sense of compassion and justice is beyond reproach? And are their actions changing what (and who) matters in a particular situation?

You will almost certainly learn something new about each of the 14 people who are profiled, and what you learn could be an inspiring event or an uncomfortable fact with which you were previously unaware. Quite conceivably your view of them will never be quite the same. The authors want us to reflect on those moments in our own lives and consider how we might have acted, and how we should act when challenged. Not how we might act in spite of our own imperfections, but with the full awareness that life constantly presents us with the opportunity to do the right thing – the moral thing – and to inspire others to do the same.

Moral Leadership for a Divided Age:

Fourteen People Who Dared to Change Our World

David P. Gushee, Colin Holtz

ISBN: 9781587433573

Brazos Press

Carlo Uchello is a member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria, Virginia, where he serves as a Lector/Chalicer and on the Altar Guild. He has previously served on the Adult Education Committee.