by Daniel Frank

A cherished favorite in the cache of Anglican hymnody, the text of My Song Is Love Unknown was composed by Samuel Crossman, a minister of the Church of England and an English hymn-writer of the 17th century. It is most commonly associated with the tune that composer John Ireland wrote specifically for it entitled Love Unknown. In 1918, at the request of his friend Geoffrey Shaw, he wrote this tune down on a piece of scrap paper within 15 minutes. The hymn had its first publication the next year in Shaw’s Public School Hymn Book.

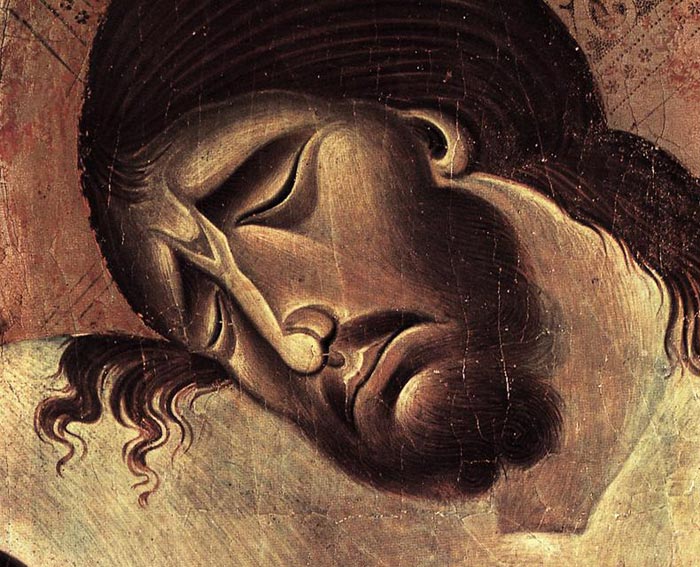

In the text, Crossman retells Christ’s Passion and emphasizes the divine love that Jesus gives us through his death. With the question posed in the first verse, “O who am I, that for my sake, my Lord should take frail flesh and die?”,a sense of wonder, humility, and (arguably) bewilderment are expressed as the author recounts the sacred story. After the intensity of the betrayal and crucifixion, grief and sadness are elicited in the mournful verse, “In life, no house nor home my Lord on earth might have; in death no friendly tomb but what a stranger gave…” followed by Crossman’s declaration that he will sing this story in remembrance of God’s ultimate act of love. The writer reminds of something I think we miss when remembering the cross and crucifixion. We can become so caught up in the gruesome melancholy of the crucifixion, we forget that this is a love story; one between God, and humanity.

Some years ago, at the first parish where I was organist, my rector had carved a great wooden cross for Holy Week and Easter. It was formidable, rugged, and (quite honestly) somewhat grim and jarring to me. Shortly after we celebrated the Great Vigil, I mentioned to my friend “I hope he’s going to put that cross away before Easter tomorrow.” With perplexion she asked “Why?” I responded “It just looks so…morbid.”

The next day, I saw the same rugged, thorny cross as I had the night before when I called it “morbid;” but it was not the same cross. Something about it had changed. What once looked like an instrument of agony and death now seemed to have a glimmer of radiance, a quiet air of triumph. The cross almost seemed to smile. My friend did not respond to me after I called it “morbid,” and I realized why after I saw what she could see. I emailed her the next day, telling her about my change of view. She responded “It takes everyone a few minutes, or a lifetime to see life where there had been death. Sometimes people never see that.”

The cross represents a story, as is the function of a symbol; and there are two sides to that story, which are inherently intertwined. A macabre story, full of pain and sorrow, is also a tale of love; a love that God shares with us every day. God becomes vulnerable through Christ when Jesus shares in the human experience of pain and sorrow. Out of that sorrow comes love. Out of that mourning, comes dancing. The “Love Unknown” that Samuel Crossman experienced is the wondrous, indescribable relationship that he felt when he thought of the love his savior had for humanity, to take our frail form and be one of us; a divine human, who craved nothing more than to be fully and intimately connected to us.

Many theologians and biblical scholars have described the crucifixion as a marriage ceremony. Christ (the Bridegroom) joins and gives himself to his betrothed (the Church; or, to use another word, us). The idea of the relationship between God and humanity being a love affair is recurrent in the Bible, especially in the Song of Songs and the Revelation to John; and in a relationship, love must go both ways. As God gives, we receive and then give back. The hymn-writer Isaac Watts once wrote “Were the whole realm of nature mine, that [would be] an offering far too small; love so amazing, so divine, demands my soul, my life, my all.” This week, think of the different ways that you feel God’s love in the world; think of the different ways in which you put love back into the world.

Dan Frank has worked in church music for the last nine years, serving as organist and music director of many parishes, including St. James’ in Arlington, VT, and St. Andrew’s in Albany, NY. He is a lover of church music history who now lives in Brooklyn, NY. When he is not trying to learn every instrument, he is also a stand-up comic and writer.