by Bill Carroll

Note: Much of my thinking about God as generous gift-giver and the flow and circulation of gifts is indebted to Kathryn Tanner.

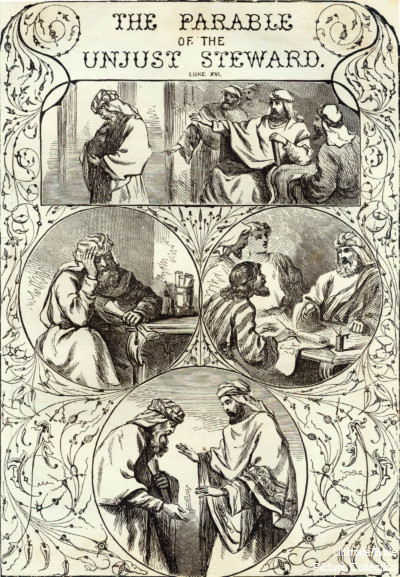

In the lectionary reading for this Sunday we encounter the parable of the dishonest steward. And I have a confession to make. I have no clue what this parable really means. And that’s okay. Because I’m not sure anyone else understands it either.

All the same, I want to dig into it a little bit, because we don’t need to understand a parable perfectly in order to guess what point Jesus is trying to make.

It’s often that way with parables—these weird little stories from the Lord. Jesus is telling us a story that doesn’t make sense—one that takes something familiar and makes it strange. There’s a twist in the story, something subversive and shocking. And it’s this twist that matters. Because the story is meant to transform our notions of who God is, who we are, and what the world is like.

And so, we don’t have to justify the crime that’s committed in the story. Or even like the steward.

But nevertheless, we need to ponder why the master comes to approve of the steward’s behavior. Here’s the scandal of the story. It’s intended to offend our sensibilities. At first the master behaves in ways we’d expect. He is surprised and angered by the steward’s behavior. And so, he fires him.

But then the steward starts to give the master’s property away, writing off one debt after another. He makes friends with his master’s wealth.

Why does the master approve of this behavior? He even seems to be a little amused by the steward’s shrewdness. It’s quite a switch, isn’t it? At first, the master decides to fire the steward, but NOW he approves? In the world as we know it, the master would fight tooth and nail to get his property back.

And then, here’s Jesus telling us to make friends for ourselves by means of dishonest wealth. Because we can’t serve both God and Mammon.

I am persuaded the key to understanding this parable is what Jesus says elsewhere in the Gospel of Luke. In chapter four, in a kind of inaugural address as the world’s true king, Jesus proclaims forgiveness from debt and freedom from slavery.

He is drawing on the so-called jubilee tradition of the Old Testament. You can see it in Isaiah and Leviticus, and elsewhere in the Bible. According to that tradition, because God set Israel free from slavery and gave them the promised land as a gift, every seven (and then every fifty) years, there’s a periodic reset built into their economy.

I’m not sure these laws were ever followed very closely, but it was supposed to work like an automatic bankruptcy where everyone starts over. Land that’s been sold reverts to the family who received it in the Exodus. People who’ve sold themselves into slavery are also set free. And all monetary debts are canceled.

In Luke, chapter four, Jesus reads from the scroll of Isaiah about this “year of the Lord’s favor.” He then proclaims to his hometown synagogue that “Today, this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” Throughout Luke, Jesus proclaims forgiveness of debt, both literally and as a metaphor for sins. Remember Luke’s version of the Lord’s Prayer, which many Christians still use, “Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” And then, finally, there’s the parable about the slave whose master forgives him a huge debt, only to see him go out and wring the neck of another slave who owes him twenty bucks.

In light of these other stories about debt in Luke, we start to see what Jesus is driving at in the parable we heard today. Both in terms of money and in terms of sin, we can afford to be more GENEROUS with our neighbors. Because God has given us all we have and all we are. And God is astonishingly generous and forgiving to us all.

In fact, there’s a way in which Jesus himself and all who follow him are called to be like the dishonest steward. For we have been authorized, in the power of the Spirit, to forgive people their sins. Sin is a debt we owe only to God, and yet we are authorized to cancel that debt for each other. So often, we picture God like a master who expects the very last penny he’s owed. By the end of Jesus’ story though, the master isn’t driving such a hard bargain. He is much more like the Father in the parable of the Prodigal Son. He, like that Father, is willing to overlook the failings of the wayward son.

In fact the Prodigal Son comes right before the Dishonest Steward and right after the Gospel we heard last Sunday about the lost sheep and the lost coin. In the Dishonest Steward, Jesus is still responding to the grumbling of the scribes and Pharisees, who don’t like the sinful company he keeps. He is claiming the prerogatives of God for himself. As the Messiah, he has come to cancel our debts and forgive our sins.

And that is where the mind-blowing revelation of God comes in: God doesn’t need a “return on investment.” God is not bound by the laws of scarcity–the worldview that defines our thinking when Mammon rules the roost. God can afford to be cheated. God can afford to forgive. God forgives not just petty losses but losses that (in the world’s terms) put our well-being at risk. In the end, GOD gives his life for us sinners, without compromising his boundless abundance and power.

And so, God approves of the foolish and wasteful misuse of his gifts on those who don’t deserve them. God approves of us giving each other second and third and fourth chances. God approves of us forgiving each other seventy-seven times. (In some cases, no doubt, with appropriate boundaries to preserve our physical and emotional safety.) For God does not give in order to be repaid. God has no need for control. Think about it: if God kept a ledger, we’d never be out of debt.

But, in Jesus, our bills are marked paid. We have a fresh start and a new life. The works we do are not to earn God’s favor, but to say thank you. Martin Luther once put it this way: God doesn’t need our good works. Our neighbor does.

God is not a Master, but our Creator.

He creates out of nothing.

God is not a creditor, but our Savior.

He gives his life for us all.

The Rev. Bill Carroll is the Rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Longview, Texas