In 2015, I moved from the San Francisco Bay Area to Knoxville, Tennessee, both for work and to be closer to family. (I recently moved to Idaho.) I found riding a bicycle on Tennessee roads to be challenging. Some of the roads are clearly-marked with bicycle lanes, but cars barely notice. Most roads do not offer bicycle lanes and many cars zoom past cyclists on the upside of blind hills, barely missing oncoming cars. As a cyclist in Tennessee, I would avoid such roads whenever possible, and when a car would approach me from behind, I would pull over so that car could pass me safely. I’d rather not be responsible for a head-on collision, just like I’d rather not get run over by a car. Seems like cars and cyclists ought to work in concert, rather than oppositionally.

In the Bay Area, more people bike to work than they do in Knoxville, but – at least when I lived there – California drivers and cyclists were equally disgruntled one with the other. I recall antagonistic letters published in the San Francisco Chronicle by cyclists and drivers, each complaining bitterly about the other. One driver wrote that she was sick and tired of cyclists running stop signs and ignoring other traffic laws. Another complained about cyclists taking-up an entire road, two and three bicycles deep, just so cars could not pass. Cyclists, for their part, complained that cars passed them without adequate clearance, jeopardizing safety and forcing many of them off the road. One cyclist described a car that cut her off by turning right directly in front of her – without signaling or yielding the right of way, as required.

A cyclist thinks like a cyclist and a driver thinks like a driver, each dualistically and somewhat exclusively, but perhaps you can see the irony and pitfalls of such either-or thinking. Some of us happen to be both cyclists and drivers. We ride for pleasure and drive for work, or drive for family and bike to work. I ride my bike in early mornings for exercise, but many days I drive to meetings and hospitals. I know fathers who drop their kids off at school and then take a bike ride for solitude. One friend rides her bike to work, and drives home at the end of the day, only to reverse the process the following day. In other words, so very many cyclists are drivers, and many drivers are or have been cyclists. Wasn’t it Pogo who said, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”?

American politics and American religion are equally dualistic. You are either Republican or Democrat. You are either conservative or liberal. You are either Catholic or Protestant, evangelical or progressive. Politics and religion treat life as oppositional, about the opinions a person holds, the beliefs held. But as my favorite bumper sticker warns, “Don’t believe everything you think.”

Does dualistic thinking make one a better Christian, or worse? I am convinced that God cares far less about any particular position I hold than about the way I engage the people around me. Indeed, Jesus criticized the Pharisees for adopting a right and wrong (dualistic) approach to religion. Love God, Jesus confounded them. He never said, be right, but rather, love your neighbor. Paul observed that being Christian is about one’s approach to people first: Love does not insist upon its own way. For James, pure and undefiled religion was active: to care for orphans and widows (those in need) and to keep oneself unstained from the world.

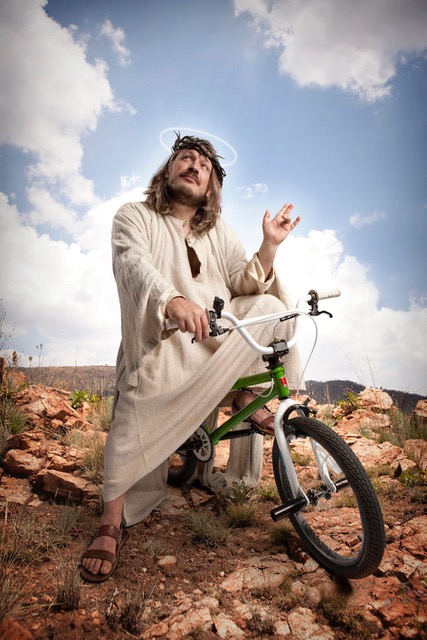

Pope Francis visited the United States three or four years ago, and both Democrats and Republicans clamored for his attention. I suppose each party assumed the Pope would like theirs better. Or, their positions. (pro-life, against capital punishment, etc.) Yet, the Pope seemed to understand that a faithful life is not first about correct positions. As one politician correctly anticipated, “I’m sure the pope will make everyone very uncomfortable. There will be some things that Democrats may not like to hear, and there will certainly be some things, I think, the Republicans will not like to hear.” Sounds like the Jesus I know. He rides a bicycle to preach and drives a car to synagogue.

I find myself driving a car and needing to turn right. There is no bike path, yet a cyclist is riding alongside to my right. Do I have the moral right to turn into her just because I have the legal right to do so? That question, though, shows how faulty questions can be. The better question is, What would love do? I’m not in a hurry, and they are enjoying the open-air breeze. Think I’ll slow down to share my right-of-way with them.