Jesus seems to have spent a lot of time teaching at dinner parties. He also had his feet anointed by several women at dinner parties. In Luke 5, Jesus was at a dinner at the ex-tax collector, Levi, at his house. Levi was the tax collector who gave up everything to follow Jesus, but was still well-to-do enough to host a grand feast in Jesus’ honor. And he invited all this tax collector friends. And the self-righteous Pharisees and scribes stood around and clucked amongst themselves at the rabbi who consorted with sinners and low lives. But the physician came to heal the sick, Jesus taught, and the bridegroom to celebrate with his guests, and in good fellowship wine flowed (Lk 5: 27-35).

Throughout Luke, Jesus moves effortlessly through encounters with those of all class, of all status, reaching out in compassion to the people in need, in pain, in affliction, in hunger for the Living God. Jesus has been going from town to town up and down Judea. Meeting people where they were. Where they hurt. Leprosy, paralysis, withered joints, even raising from the dead the only son of a widow. Going from one place to another bringing the Light of the Holy One into incarnation, visible, if not yet understood. And now he is invited to dine with some Pharisees, where he is disrespected by his powerful host, a community leader. But honored by some nameless woman who didn’t belong there (Lk 7: 36-50).

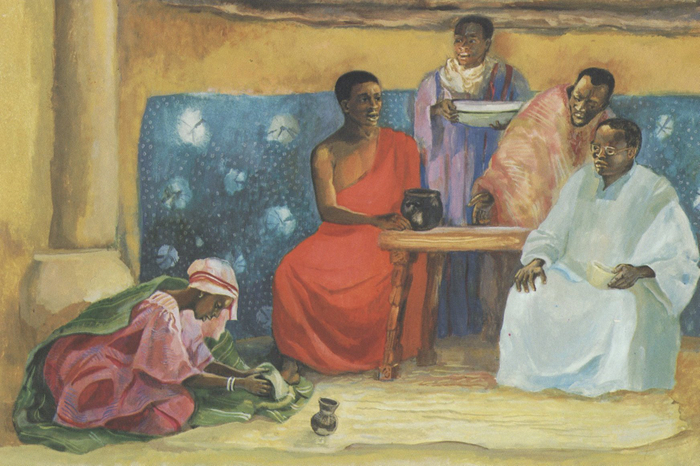

Why was he invited? Curiosity? To bait him, uncover his blasphemy, or just to question him? And how did that woman get in? Crashing the dinner party? Rich people had servants who kept watch at the front door. So how did she get in? All we are told is that she knew where Jesus would be and sought him. She suddenly appears, holding an alabaster vessel filled with ointment, and stands behind Jesus. But even before she is moved to tears of love and repentance, much strangeness was already in the air. Why hadn’t the host ordered a servant to wash his guest’s feet? That was the first century Jewish version of hot water and a scented towel to wash your hands. Why hadn’t Jesus been greeted with a kiss, the two cheek kind of air kiss you still see in the Middle East and Mediterranean? No sweet oil for the guest’s head? Bad manners? Intentional disrespect? It isn’t until the woman has washed his feet with her tears and dried them with her hair that Jesus speaks up about his host’s neglect, and then only after the woman had been disgraced by her so-called betters. Suddenly both Jesus, the dishonored dinner guest, and the woman, the dishonored sinner, are on the same level. And what was her sin? We, well trained by eons of innuendo, immediately assume she was a prostitute. But what if she was just a woman divorced for not producing a male child. Or living with a man, but unmarried, as was the woman at the well. Or a woman at the beck and call of one of the men there. All we know is that she is ashamed, aching for a love she finds in the healer, miracle worker, prophet. A hand reaching out to her, perhaps to touch her head as she cried her heart out without words, overcome by the totality of a life in shame, fear, want? What was her sin? I think sex was the least of it. Perhaps her sin was that she was in such want that she was incapable of reaching to God, a God who lived in the Temple in Jerusalem, who required purchase of sacrificial animals. A woman for whom following the Law was made impossible by social rejection and poverty. And yet she came with an alabaster jar of ointment to anoint Jesus’ feet, and act of abject servitude. Offers her tears, her hair, acts of intimacy. Of profound devotion. And asks for nothing. We only know that she was drawn to Jesus, as many of us still are. By his love, kindness, protection.

And he forgives her of her sins, absolves her of her shame, grants her the freedom to turn in a moment of metanoia, of repentance, of truth. That is the great sign that Jesus bestows on us still. It is perhaps too cynical to point out the ancient belief in demoniacal or sinful causes of disease. To this day we blame disease on smoking, drinking, or a fondness for red meat. Or even vaccinations. We have our own superstitions. While we can be made sick by bad air and water, all this is a distraction. What Jesus came to do was heal sin, to turn people toward what can keep our human sin at bay. That which can heal our souls, can overcome the unconquerable – pollution, bad genes, gun violence, war, plague. What he came to teach was the way to satisfy our relentless thirst for God.

The woman at this embarrassing dinner was healed. She had been vulnerable, fearful of these powerful men, wounded by their words about her. In that vulnerability she was open to Jesus’ presence, his divinity. Her sins were many, not by counting the number of men she slept with. They were many as are ours every day. She sinned when she fought with the people she had to fight or insult to keep her meager self-respect, her identity as a human person whom, unknown to her, was beloved by God. Her sins were many because of the walls she had to put up around herself to survive, and do whatever she had to in order to survive.

Perhaps the parable about the debtor with many sins and the one with few sins could have been Jesus’ inevitable way of overturning the obvious. Could not the Pharisees have been the ones with the many sins, despite their adherence to the Law? Had any of them recognized himself as such, would not he also have been weeping at Jesus’ feet, throwing off his fine robes and following Jesus? Her sins were the sins of the neglected, of the powerless, of the socially cast away. Theirs were the sins of pride, power, self-importance.

And so he tells her that her sins have been forgiven, and “Your faith has saved you, go in peace.” Her faith in him is her newly recognized faith in his Father. She is made free, not to go and never sin again. She will have to work this out over her lifetime. With grace, she will find others of his disciples and learn more about what she has been given. She will be protected and loved in a community of faith, perhaps a sometimes quarrelsome and sinning community. But one that knows that Jesus is the way through the messiness of life to the endless mercy of his Father. We all continue to sin, but as we learn about the gift of Christ we can struggle to grow more like him, and to ask for the grace to do so. And we do so in the mundane round of humiliating dinner parties and cruelty in life, school, the workplace, even (God forgive us) in the Church. But we have his presence with us always, and our openness and vulnerability, our shame and tears, will show us back to the Way of salvation. And our sins will once again be forgiven.

Dr. Dana Kramer-Rolls is a parishioner at All Souls Parish, Episcopal, Berkeley, California and earned her master’s degree and PhD from the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.