By Dana VanderLugt

As a small child, about ages five until eight, I had a Saturday morning ritual of waking up before my parents and siblings. I liked being first up, having the whole quiet house to myself, and cozying up on the couch with a blanket and the television. This was the 80s, years before we’d get cable — and unlike my own children who can grab the remote control and activate Netflix or Amazon Prime to find something to watch any hour of the day — Saturday morning cartoons were an event in themselves. If I woke up before six, I’d have to endure the U.S Farm Report before any children’s programming came on. We had a local affiliate that broadcasted their own Bozo the Clown show, and when kids sent letters to Bozo, he’d sometimes highlight them on the program. I vividly remember one Saturday when I was in first grade: Bozo held up my letter, said my name, talked about how much he liked it. I beamed with enthusiasm, alone on that couch. I was proud, but also sad that I was the only one awake in the house to see it, hoping desperately that when everyone else in my house finally woke, they would trust my story and understand and echo my excitement about my moment of fame.

I remember watching Mr. Rogers, too, but in the kind of a vague warm way you might remember a favorite elementary teacher. When I see clips of his show today, they feel familiar. I’m unsure if I recall bits and pieces of specific episodes, or how Mr. Rogers made me feel. Like Bozo saying my name on air, Fred Rogers had a way of making me, and millions of other children, know we were seen and known. My home was a safe place filled with love but talking directly about our feelings was a foreign concept, and even a bit awkward. Mr. Rogers named emotions for me when I couldn’t do it for myself. His busy neighborhood felt both close and far from my own home on a gravel road surrounded by cornfields.

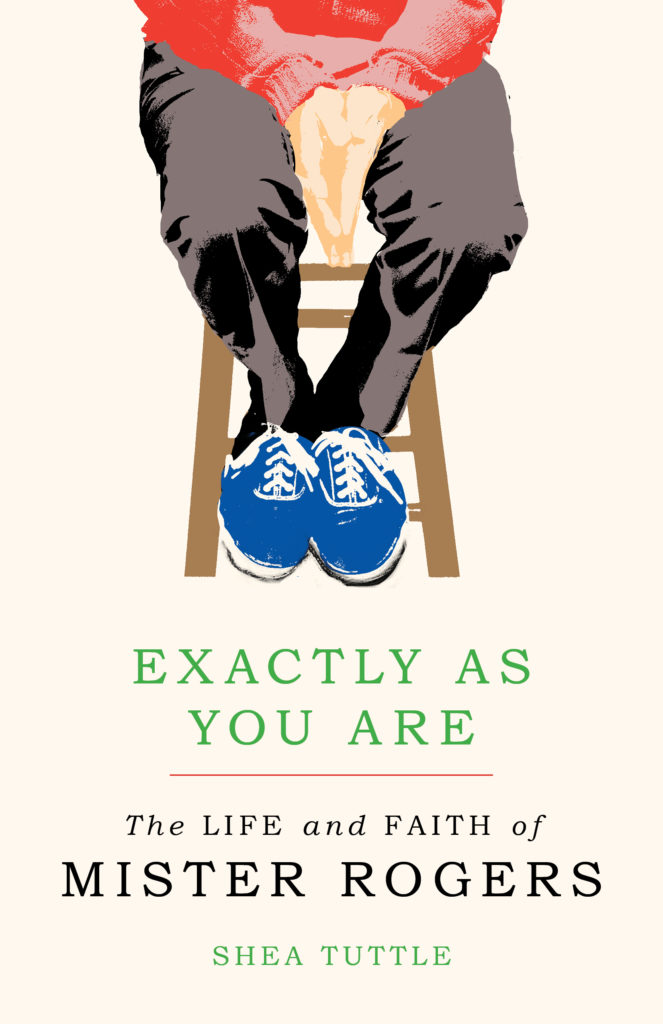

Shea Tuttle’s book, Exactly As You Are: The Life and Faith of Mister Rogers, gave me new eyes to examine Fred Rogers, while also helping me to understand what it was about this man that made me aware, even at a young age, that he was different from other television personalities and his program was different from other television shows.

From the first lines of the book, viewing Rogers through the lens of his faith seems organic and necessary. In fact, his DNA is so tied to his faith that I found myself wondering not how Tuttle managed to weave Rogers’s spiritual convictions into his life story, but how someone might separate this out. From his childhood faithfully attending Sunday services at Latrobe Presbyterian Church, to his seminary training, to the practical ways he conducted himself on and off the screen, it’s abundantly clear that Rogers saw his calling not as children’s entertainment, but as deeply theological work. Rogers, in a 1971 interview, said his work pointed to the incarnation itself. As Tuttle explains, “God cared, Fred believed, enough to be among us and to feel every human feeling, and so Fred worked hard to be with children in their feelings, to explain and alleviate when possible, but more importantly, to take seriously — as seriously as God becoming human.”

The book, and Fred Rogers’s entire career, rests firmly in its first section, “Becoming Mister Rogers,” in which we are introduced to his safe and secure home in the midst of the fears and insecurities — in the form of bullies, loneliness, and sickness. “Fred knew intimately the current of fear mixed with elation that runs through so much of childhood, the electricity of the outside world that makes the return home so sweet. So he worked hard, every day of his television career, every time he looked directly into the camera’s lens, to offer something of that home to the children who watched. In that space between his gaze and the gaze of each child watching, he created an intimate world of safety and calm” (13).

For me, the thread that ran through the book and caused me to underline sections and take pictures of pages to send to friends was Fred Rogers’s intentionality, the connection that seems to run from his heart straight to his hands and feet. In a society that seems rushed — rushing children to grow and rushing us from one task to the next — this book contained deep wisdom and a solid example of how Rogers’s faith was an anchor that allowed him to hold tight to what mattered most, while also evolving as he discovered the next right step. As Tuttle writes, “Throughout his almost fifty years in television, Fred said not to every voice (perhaps even some internal ones) that told him that to do such and such would generate better ratings or bigger profits: ‘no’ to picking up the pace, ‘no’ to animation; ‘no’ to licensing of merchandise; no to moving Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood to network television or even to a bigger city like New York or Los Angeles. And as he said no to greater speed, more money, and higher ratings, he said yes to quieter good; thoughtfulness, intentionality, and his own intuition and imagination for the work” (36).

Without idolizing Rogers or making him superhuman, Tuttle sheds light on Fred Rogers’s life in a way that has the possibility to illumine and instruct our own practice of faith. And like a child, sitting groggy-eyed and alone on a couch on a Saturday morning hoping to be seen and noticed, the book also quietly reminds of us that the truths Rogers spoke and lived still apply to us as adults: that we are seen and loved exactly as we are.

Exactly As You Are: The Faith and Life of Mister Rogers

Exactly As You Are: The Faith and Life of Mister Rogers

by Shea Tuttle

Dana VanderLugt is a teacher and instructional coach pursuing an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. Her work has been published in Longridge Review, Seeding the Snow, Ruminate, and The Reformed Journal, and The Twelve blog. She blogs at www.stumblingtowardgrace.com.