by Laurie Gudim

The story of the rich young man who comes to Jesus looking for eternal life is really tough. I’ve heard many sermons designed for us First World people that put it in a palatable context. And still I am left with a niggling doubt. It seems to me that the fundamental issue is that it is really, really hard to have stuff and not to be at least to some degree enslaved by it. (Think, for instance, of the times you’ve had to plan your life around getting repair people in to fix a furnace that has gone on the blink or a sewer that has backed up.)

The young man was not a slacker. He had been following the law since his youth. He was one of those genuine, fervently-religious people who try to put their relationship with God first, before everything else. But he had many possessions, and he didn’t want to let go of them. And it probably wasn’t that he loved the stuff so fiercely. More likely he believed that he needed it all. Perhaps he was thinking of the security of his family or of the status he would lose if he were to sell his things. Maybe he feared the inability to take care of himself if he were injured, or the incapacitation he might experience as he grew old. Or it could have been that losing his stuff meant losing, to some degree, his identity. In other words he probably had the same issues that any of us would face if Jesus, point blank, asked the same thing of us.

I am totally humbled, completely flattened, by this story. The most altruistic acts and the most extensive giving are as nothing if this is the standard for Kingdom of Heaven consciousness. This is total dependence, not on our own agency, but entirely on God.“ Let God take care of everything. Let it go. Come and follow me,” says Jesus. And, “Camels get through the eyes of needles more easily than rich people (which, face it, means all us First World people) get into the Kingdom of Heaven.”

I’m with the disciples in their lament, “Then who can be saved?” And, with all Jesus’ followers, I am reassured by the answer. “For mortals it is impossible, but not for God; for God all things are possible.

I hope that in the very uncertain times ahead I can throw myself more fully into dependence on God, stepping out in ways that might threaten my own security to support those who are in grave danger. I hope that I am able to give myself lavishly, to open my heart and my home, and to be God’s slave instead of the servant of my stuff.

But this hope is idle without God’s help. And so another kind of dependence suggests itself to me. I return to basics, to prayer – to the regular, contemplative, resting-in-God sort of spiritual practice that sustains me. Let me become transparent to the God who dwells in my heart. Let me become who God desires that I be. For mortals it is impossible, but not for God. For God this is a piece of cake.

Laurie Gudim is a writer and religious iconographer who lives in Fort Collins, CO. You can view some of her work at Everyday Mysteries.

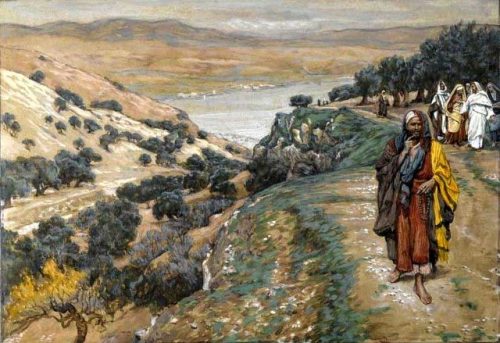

By James Tissot – Online Collection of Brooklyn Museum; Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 2007, 00.159.159_PS2.jpg, Public Domain, Link