This year I participated in a Lenten series on end-of-life issues and dying. One presenter asked us to imagine the best of all possible deaths. What would that look like for each of us? Where would we want to be and who would we want there with us? What sounds, sights and smells would we like to surround us? How would we like our pain to be handled? Who would make decisions for us as to how to proceed in terminal care?

Most of us wanted to die at home or in hospice, with an opportunity to say goodbye to family and friends. The ideal pain management would be that we would be allowed periods of greater lucidity and suffering in which to have meaningful conversations with loved ones and longer periods in which we would be allowed to drift in relatively pain-free oblivion. We didn’t want to be too aware of our bodies as they shut down, especially not our lungs.

Having just read today’s passage in Mark, I feel pretty silly. Don’t get me wrong. I think it’s hugely important to think about and have conversations with our families about dying. It’s helpful to our children, for instance, not to have to guess whether we would want to be resuscitated and whether we would want feeding tubes put in.

But this was a discussion happening in a church group. And not one of us, not a single soul, imagined the most holy death of all, the one that would occur in a gutter or a gulag, or by execution in some god-forsaken corner of the world or, God forbid, in your own home, while helping people who are in desperate, unremitting need.

When Peter rebukes him for talking about torture and death at the hands of political authorities, Jesus tells his disciples that human concerns are not divine concerns. And that raises the question. What are divine concerns? There are a couple dead ringers mentioned often in scripture: loving one’s neighbor, speaking truth to power no matter what the cost, and living a life of service no matter what the risk.

But here’s the more comprehensive question: how do we follow the Way of Jesus in the individual manner for which each of us was uniquely created by God? How do we follow that Way no matter where it leads us? This will not necessarily confront us with real-time, life-or-death choices. But we will face the thousand small deaths: looking stupid – or crazy – or making ourselves worthless in the eyes of those we rely upon.

Paradoxically, living the life we were created to live is exactly the same as denying ourselves and taking up our crosses. Deeper than the wishes of friends and family, deeper than cultural expectations – deeper even than personal desire, or personality itself – the true self reaches out in union with God and makes demands of us. When, in answer to these demands, we become outcast, that’s a cross. When we take a stand that causes people to scream at us, abuse us or abandon us, that, too, is a cross.

Divine concerns lead us out beyond the edge of what is usual into deeper relationship with God. Human concerns limit us to the narrow perspectives of our own egos. Let us pray that grace allows us the greater reach – and that we take up our crosses again and again as followers of the radical Messiah.

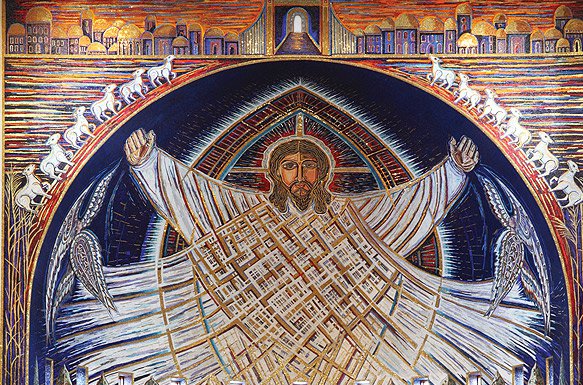

Laurie Gudim is a writer and religious iconographer who lives in Fort Collins, CO. You can view some of her work at Everyday Mysteries.

Image: By Karemin1094 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons