by Julie Hoplamazian

The Christian tradition is rich with spiritual disciplines. There are sets of practices, some dating back many centuries, that have remained central today: the daily office, lectio divina, daily Scripture devotions, prayer beads/rosaries, praying with icons, centering prayer, to name a few. Just like athletes have training regimens, people of faith need spiritual disciplines to strengthen their relationship with God.

When I was a candidate for ordination, my bishop laid out the clear expectation that we pray the daily office every day for the rest of our lives. I don’t remember the exact words he said, but the impression I got was that this was an essential spiritual discipline for a faithful priest. Along the way, I’ve engaged this and many other “church-sanctioned” spiritual disciplines, many of which are named above. While I have loved some, to be honest, not all of them have stuck. I tried for 2 years to pray Morning Prayer every day, until I couldn’t bear it anymore. On the other hand, when I’d go to ballet class, I’d feel my soul sing, feel God alive in my veins, in ways I never did through the prayer book. I thought of the words of St. Paul: “But strive for the greater gifts. And I will show you a still more excellent way.” (1 Cor 12:31) I struggled with the fact that in striving toward the gift of prayer, a more excellent way was not something the church would “approve.”

The danger with focusing on a particular spiritual discipline is that it can glorify the means, not the end. I’ve been in situations where I was totally shamed for revealing that I did not pray the daily office regularly. It saddens me that these disciplines are sometimes used as measuring sticks to judge another person’s faith. It turns a meaningful spiritual discipline into a golden calf.

The goal of our spiritual lives is not to engage in prescribed spiritual disciplines, as effective as they may be for a large number of people. There is nothing wrong with the daily office, or lectio divina, or centering prayer, or daily Bible devotionals. But there is something wrong with glorifying the means of connecting to God, rather than the end of connecting to God. Our task is not to do X, Y, or Z. It is to listen to God and grow in relationship with and love of God. It’s about prayer, not piety. It’s about relationship, not “the rite stuff.” (Sorry, I had to.) And because God is revealed to us in a variety of ways, our job is to be attentive to that which draws us genuinely closer to God. Our task is not to answer the question “What am I doing?” but “How am I listening?”

Maybe reading your Bible every morning does that for you. Maybe the daily office does. Maybe it’s yoga. Maybe it’s golfing with your buddies. Maybe it’s a half hour of silence every day. Maybe it’s walking your dog. Maybe it’s a ballet class.

And yes, some of these things are, for many people, regular everyday activities that aren’t intended or designed to connect us to God. And yet, there are others who experience God more powerfully through these disciplines than they ever would by praying the daily office. The point is your intention and attention.

We are about to enter the season of Lent, when this conversation about spiritual discipline kicks into high gear. It’s almost like the Olympic trials of personal piety. This year, resist the temptation to compete in the games.

Step away from what you do. Step into how you listen.

What, then, does it mean to be spiritually attentive? Here are some indications that you might be on the right track:

First, it is an experience of a sense of transcendence, a touch of the divine, a connection to something much larger than yourself. Being spiritually attentive means that whatever the thing is you’re doing, there’s something deeply embedded in it for you that awakens in you the knowledge of the reality of the world as God’s, and you as a part of it.

Second, it gives you a deep sense of contentment and joy. Not giddiness, or even happiness, but a deeply rooted centeredness. It taps into the core of your being – your soul.

Third, though it might not be something you do all the time or every day, it should be something you know that once you do it, you’ll feel “better.” Not good necessarily, but reoriented. It should help clear the muck in your heart, mind, and soul.

Fourth, spiritual attentiveness means that whatever you’re doing connects you to God’s Word. For example, when I take a ballet class, we end with a “reverence,” or a bow of gratitude for the whole thing. That practice, for me, brings the Scripture to life: “And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.” (Col 3:17) Spiritual attentiveness means that the thing we’re doing opens the Word of God to us in ever-new ways.

Spiritual disciplines assist us in spiritual attentiveness. The tried and true methods of spiritual practice that have lasted for centuries are indeed valuable, sacred, meaningful ways to attune our ears to the sound of God’s voice. And yet, we also believe that God is revealed to us in an infinite number of ways. As Ignatius of Loyola instructs, we are to “find God in all things.” My spiritual director is rooted in Ignatian spirituality and has shared this quote with me: “Spirituality is a series of practices that allow us to pay attention to God.” And perhaps paradoxically, the ultimate goal of engaging in spiritual discipline is to cultivate the discipline of attentiveness to God, the Creator of heaven and earth. So, sisters and brothers, how will you listen?

The Reverend Julie Hoplamazian is an Episcopal priest, currently serving as the Priest Associate at Zion Episcopal Church in Douglaston, NY. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two dogs.

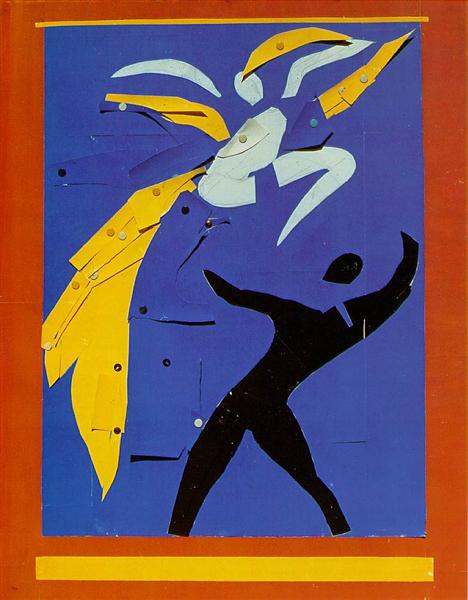

image: Two Dancers (Study for Rouge et Noir) Henri Matisse