by Tricia Gates Brown

“Moses agreed to stay with the man, and he gave Moses his daughter Zipporah in marriage. She bore a son, and he named him Gershom [alien]; for he said, ‘I have been an alien residing in a foreign land’” (from today’s lectionary reading in Exodus 2:15-22).

The Hulu series “The Handmaid’s Tale,” based on the novel by Margaret Atwood, takes place in a dystopian United States where the vast majority of inhabitants can no longer have children. In response to this crisis, an authoritarian governmental structure allows those in power to subjugate fertile women, forcing them to work as “handmaids” (sex/birth slaves/surrogates) for elite families. Taken from their own families by paramilitaries, the handmaidens must live under the watchful eye of the state, are granted no rights, and are treated like servants. Fear of being singled out for punishment overshadows their days, and as we hear through the thoughts of Offred, the main character, they are allowed freedom only in the alcoves of the mind. In the view of elites who control them, the maidens are sub-human; yet the maidens hold the keys to life. As life-holders, they have the power in a society where fertility is perilously low. Because of this fact, it is all the more important that an elaborate system keep them isolated, disenfranchised, and afraid—thus, unable to see their inherent leverage.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” portrays a chillingly patriarchal society where women—whether the handmaids or the wives who share their husbands—are strictly controlled by males. I doubt there is a woman who watches this series without a twinge of discomfort, recognizing traces of familiarity in the domination. Still, what I observed as I watched the series was how the nearest modern-day equivalent to the experience of the handmaids, the nearest equivalent in today’s United States, is the experience of many undocumented immigrants. That group tarnished in mainstream news with titles like “criminal,” “illegal alien,” and “thug.”

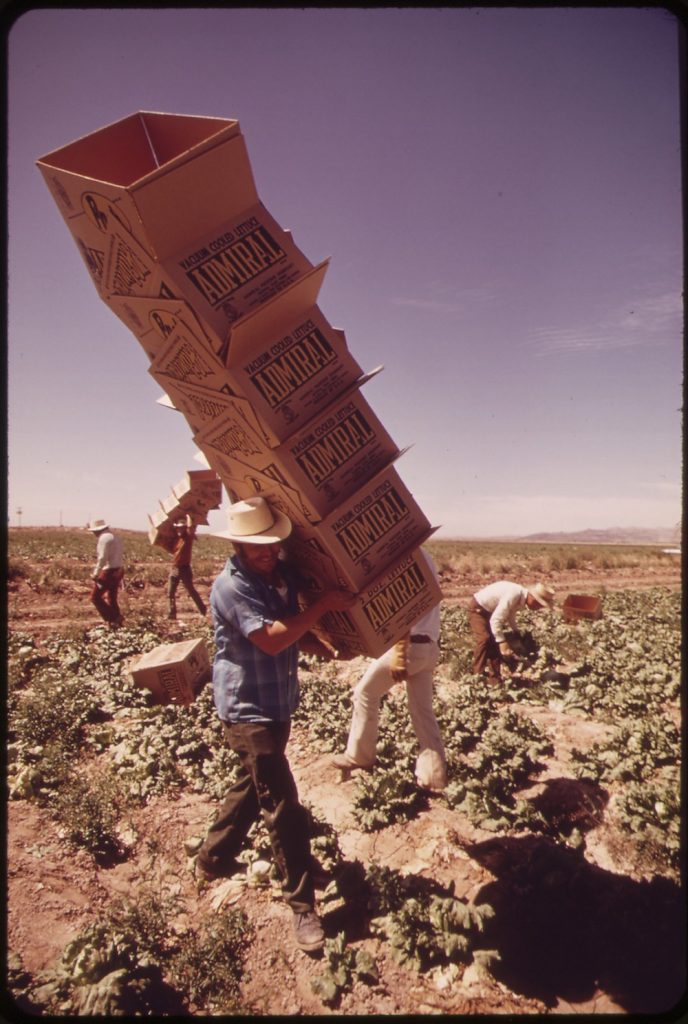

Like the handmaids, the undocumented do what the average American is physically or psychologically unable to do. In our economy, the undocumented do the most challenging aspects of physical labor. As the workers who pick our produce, process the foods that appear in our grocery aisles, milk the cows, and prep our meals in restaurants, the undocumented hold the keys to life—insofar as food is life (this aside from work they do raising young children, caring for the aged, putting roofs over our heads). The fact is, Americans cannot hold up our food system on our own. We depend every day on the work of people who come to this country to fill jobs we cannot do. But lest these workers realize leverage in the system that depends on them, US authorities have in place an elaborate system of control. While bipartisan efforts have in the past tried to humanize the system for these integral contributors to our economy, an effort is currently mounting to harshly control and curtail the movement, freedoms, and experiences of undocumented workers in the United States. This is what stood out to me as I watched “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Especially as some at the highest levels of government describe undocumented immigrants as degenerate (“drug dealers” or “rapists”), or imply we will garnish their wages to pay for “a wall,” or encourage the building of for-profit prisons to house the less productive among them—notably, women and children.

Undocumented people come to US willingly; they are not abducted and brought here. I am not implying otherwise. But they are sometimes fleeing violence, as in the case of many Central Americans and Mexicans who flee drug wars fueled by American addiction. Other immigrants are economic refugees. Though they are not abducted, they are separated from their families because no good choices remain for them. I am not saying the undocumented experience is the same as that of the handmaids. But the echoes and resonances, the shadowy resemblance between the circumstances of the undocumented and the handmaids, should give us all pause.

Most Americans do not personally know undocumented immigrants (or don’t know that they know). Fewer still are familiar with the in’s and out’s of US immigration law, or the extent to which undocumented immigrants contribute to our economy while having virtually no rights and no viable pathways to legitimization. Maybe, then, it would be fruitful for people to watch “The Handmaid’s Tale” with the undocumented in mind. Then to take some small or large step in support of them.

Judeo-Christian tradition emphasizes the importance of hospitality toward “the alien,” meaning the stranger in a foreign land. It is not hard to see why. The tradition tells the story of a people who often find themselves as strangers in a foreign land—from Abraham, who is told to leave his homeland, to Moses, who flees Pharoah’s home for Midian, to the Hebrew people he leads out of Egypt, to the Israelites in the long, painful exile that gave birth to such powerful Hebrew scripture, to the experience of the Israelites as strangers in their own land under a succession of dominating empires, to Jesus, a stranger compelled to take his transformative message from Nazareth to the churning pot of Jerusalem, to the men and women who, transformed by that message, leave their homes to proclaim a radical counter narrative—the upside-down reign of God—throughout the Roman Empire. The Judeo-Christian tradition is a tradition of immigrants and strangers. Proclaimed well, it offers hope to immigrants, to the “outsider.” It is equally a rebuke to those chanting: “[Insiders] First!”

With the events at Charlottesville and our President’s in-the-end tacit support of hate groups, many see more than ever the need to shine a bright light on the tide of white supremacy advancing in our country. Anti-immigrant hate speech is a core component of rhetoric among these groups. We refuse to downplay the seriousness of this moment, or fail to apprehend how dangerous it is for all people of color, including immigrants. Those of us in the Judeo-Christian tradition can speak boldly from our tradition against these movements, and against efforts to further disenfranchise undocumented workers. As Bishop Jake Owensby (Episcopal Diocese of Western Louisiana) stated, “Racism is a sin. White supremacy is a racist ideology. Its presence in Charlottesville was undeniable. It is our responsibility as followers of Christ to denounce this hate and violence without resorting to hate and violence ourselves.” Especially, critically, when Christianity is being coopted to promote the domination, as it is in American white nationalism, as it was in “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

Tricia Gates Brown works as a writer, garden designer, and emotional wellness coach in Nehalem, Oregon. She holds a PhD from the University of St. Andrews. In 2015 she completed her first novel and the essay collection Season of Wonder, and is currently at work on her second novel. For more, see: triciagatesbrown.net