Daily Office Readings for September 11, 2020:

AM Psalm 40, 54; PM Psalm 51

Job 29:1,31:24-40; Acts 15:12-21; John 11:30-44

We often talk about someone having “the patience of Job,” but as we see in our first reading today, Job was anything BUT patient in laying out the case for his innocence to the Almighty.

Job’s discourse would have been recognizable to ancient audiences as “an oath of innocence.” The oath of innocence was a legal device known not only in Hebrew culture, but in Babylonian, Hittite, and Egyptian culture. When one swore an oath of innocence, it was considered not only to put one’s temporal life on line, but additionally one’s eternal life. In effect, Job’s oath of innocence indicts God for unjustly punishing Job.

It’s a brilliant legal strategy–except for one thing. It assumes suffering is punishment for sin.

We might think we’re too sophisticated to think that way, but now and then we find ourselves falling into that trap. Perhaps it’s when we hear someone who has an addiction has relapsed or ended up in a difficult situation, accelerated by past poor choices. Perhaps it’s when someone we don’t like very much suffers a catastrophic turn of events. Maybe it’s simply when someone utters that hackneyed cliché that “Everything happens for a reason”–and when we do any of these things, we’re headed down that same slippery slope Job was on, that mistaken belief that, in our self-assuredness, someone or something is to blame for suffering. In this season of hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes, we readily accept that no one person is at fault–yet in terming these “natural disasters,” even that phrase itself assumes the notion that any other types of disasters have a culprit.

Any of us who have lived long enough realize that’s not the case. Bad things DO happen to good people, to borrow the title of Rabbi Harold Kushner’s famous book–and when they do, we are often powerless to accept the randomness of tragedy. One of the most common questions I get from parishioners, in the wake of a tragedy, is “Why does God allow (fill in the blank.)” Now of course, on a good day, the person who asks that question generally knows better–God doesn’t allow or choose for those things to happen. Sometimes, stuff just happens because it can. Our mistaken tendency is to indict God rather than acquiesce the randomness of suffering. Conversely, our mistaken response is to expect God to be transactional when it comes to our own righteous acts–that somehow they are an investment that gives us the power to dodge personal tragedies.

Yet…even in the depths of Job’s mistaken assumption, God had been there with Job the whole time, as Job was laying out his case. We may not always see God in the face of our own suffering, but God was there all along. We may not ever find out a cause for our life tragedies, but we can have faith that God will be present in the healing we can claim from them.

When is a time that suffering taught us something about the nature of God’s desire to be more deeply in relationship with us?

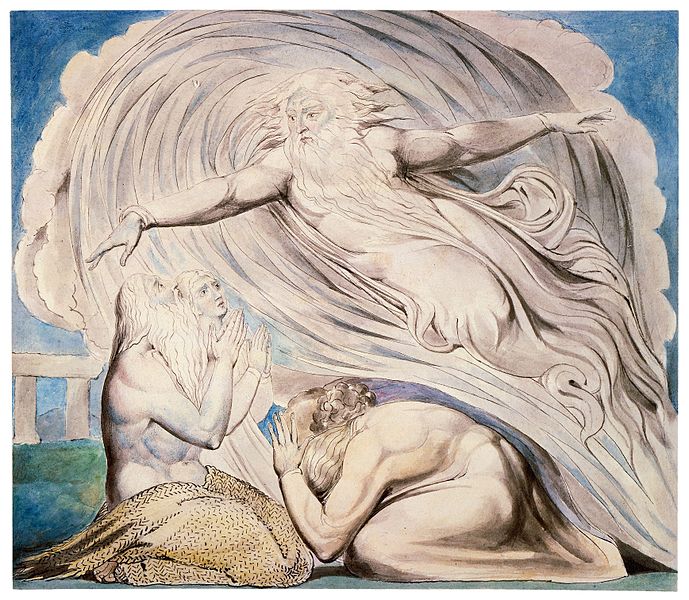

Image: One of the William Blake illustrations for the Book of Job, courtesy of Wikimedia.

Maria Evans splits her week between being a pathologist and laboratory director in Kirksville, MO, and gratefully serving in the Episcopal Diocese of Missouri , as the Interim Pastor at Christ Episcopal Church, Rolla, MO.