As I often do, I turned for inspiration for this essay to the lectionary readings of the day. Among them: two vengeance Psalms, a grisly murder narrative from Esther, and a fire-and-brimstone ditty from the Gospel of Matthew, with its characteristic presaging of weeping and the oddly outmoded gnashing of teeth. Among them, not one that sits savory on my tongue. Yet this lack itself was thought-provoking. What do we do with all this vengeance and violence?

One thing we do is acknowledge that the people writing the passages did what people in the ancient world always did—for that matter, what people still do today. They cast their enemies as God’s enemies, beseeched God to vanquish them, then told their vengeance tales as stories of divine deliverance. This should not surprise us. It is what people do.

Yet that does not make God vengeful or punishing or violent.

But wait. We actually like our stories of deliverance to have a noir quality about them—with our own personal enemies strung up by the neck, as in the Esther story, as we ourselves are ushered to lands of milk and honey. Deep down we often want our God to be the noir-God. It is the same impulse that attracts us to the strong man, or woman, in dramas. As we sit and watch the pursuit of a villain in a TV show or film, our bodies tense with the hope the protagonist’s arms will be strong enough to knock the gun out of the villain’s hand and his/her arms quick enough to aim and fire a gun to halt the villain’s inevitably destructive course. In our bodies, we feel a sense of relief and satisfaction when they do. Even if we intellectually know that violence creates more violence, even if we worry that violence is destroying much that is good in our world, our bodies feel the satisfaction on a deep level as we see violence, once again, save the day. What is going on here?

What is going on is that we’ve put our faith in violence.

Maybe we can use these experiences of tensing, of seeing our own violent longings, by becoming more acutely aware of them. Maybe we can try to tell ourselves such raw and brave truth about the experience that we see the violence close up—how it feels, how we see no other way, how we want those who have hurt us to suffer and fail as brutally as the villain. How we want to see them rot in prison, to lose their health and happiness and wealth—perhaps even their life. How we want vengeance.

But the bigger story of the Bible runs counter to these enemy-hating proclivities and actually gives our violent tendencies little cover if we are reading it well. It is always easy to proof-text—to pull out any old story or image that suits us. However, taken together, the anthology of books that is the Bible keeps showing us a God who contradicts the way we sometimes want to see God, showing us a God who is vulnerable, suffering, who mourns with and struggles with us, almost as if defenseless against our brilliant inventions. Crosses, swords, assault weapons, nuclear warheads. Our brilliantly weaponized free will.

Only after we have intimately known and fallen in love with this vulnerable, freedom-giving God and experienced divine mercy ourselves can we even begin to conceive of loving our enemies. If we try to do it by sheer effort, we fight a current—like swimming against a strong rip tide. But if we join the flow of God, which is a good way of describing relationship, we may one day understand. The long arc of the biblical narrative that we must make an effort to see, is one where divine mercy—even for enemies—keeps making an unlikely appearance despite the vengeance proclivities of human beings, and where forgiveness is shown to be the direction in which divine flow is moving. Shalom. Tikkun olam. Everything redeemed, everything belonging.

We come to know this new order from a place of belovedness. Thanks to the news cycle, these days we are especially aware of sexual violence against women—on all sides of the ideological/political spectrum, violence against people of color, violence against animals preyed upon by trophy hunters, economic violence against the poor, sick, and elderly. We must look inward with a steady eye to our own violence—each of us, and refuse to look away from our participation in oppressions. When we experience God’s love for us, despite these tendencies, our hearts begin to soften, even, hopefully, eventually, toward our enemies.

I end, then, with a long quote by Beatrice Bruteau that beautifully hints at this idea. She writes,

“The way to release [our violence], then, is to trace back the demand, to see what it is really, finally, seeking, what we really want. And when that is clearly seen, we can turn to our tradition, whatever it is, and hear it say, But you already have that. There’s nothing to worry about. Even if human beings don’t give you the respect you want, God does. Doesn’t that mean more? Even if your phenomenal human personality isn’t in the most advantageous position relative to other human personalities, your real self isn’t relative! It doesn’t have to struggle for recognition and a good position. The only ‘you’ that really matters is quite safe and in good condition. Believe that, relax, and enjoy life.”

(from Beatrice Bruteau Radical Optimism, Sentient Publications, 2002, page37).

Amen.

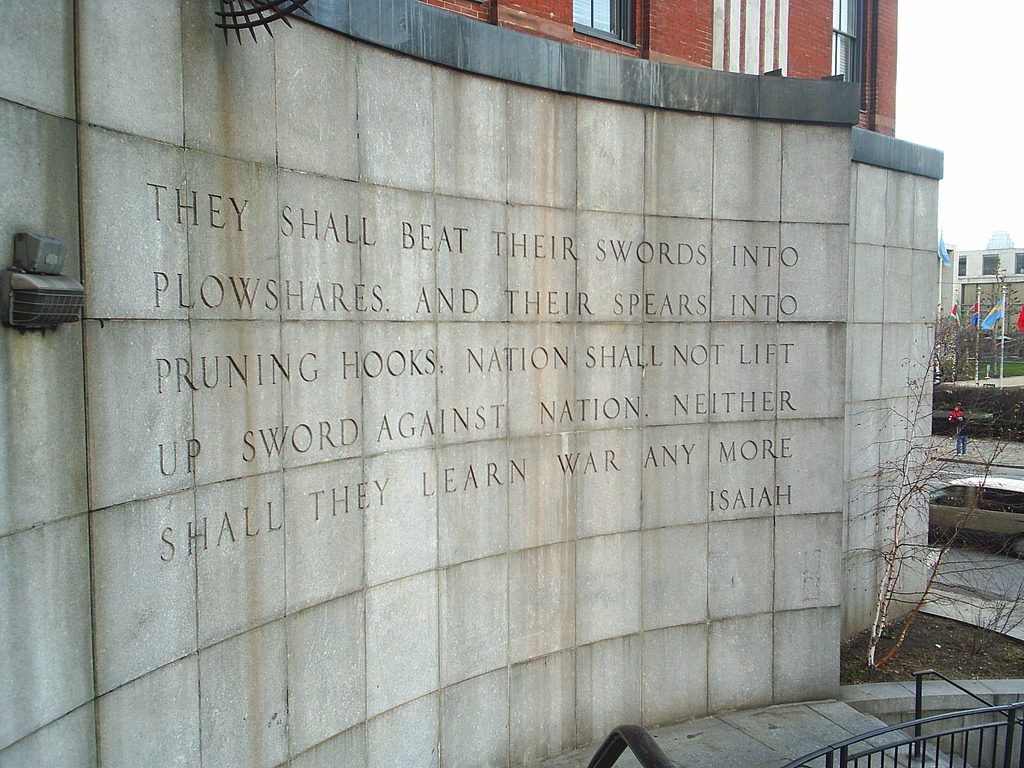

Image attribution: Isaiah Wall, By Capt. Phœbus (talk) 17:01, 31 October 2007 (UTC) – Own work, Public Domain