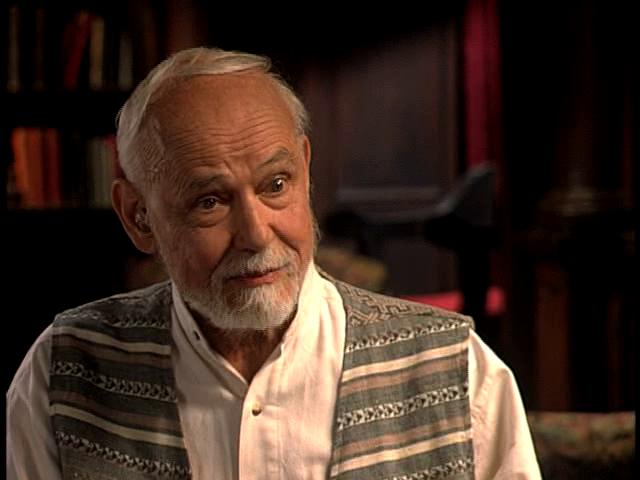

He wrote the book on comparative religion – The Religions of Man, later retitled The World’s Religions, used in college religion courses for more than 50 years according to the New York Times in a story reporting Smith’s death at the age of 97 on December 30, and remembering his life.

The book examines the world’s major faiths as well as those of indigenous peoples, observing that all express the Absolute, which is indescribable, and concluding with a kind of golden rule for mutual understanding and coexistence: “If, then, we are to be true to our own faith, we must attend to others when they speak, as deeply and as alertly as we hope they will attend to us.”

Smith reached people through television shows on PBS and elsewhere; he was an ordained Methodist minister whose work over the years included travel, meditation, yoga practice and experimentation with psychedelic drugs. He participated in the civil rights movement. He was acquainted with Aldous Huxley and, together with other colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (where he taught philosophy), brought him for a series of standing-room-only lectures.

Smith’s childhood lay the groundwork for his embrace of differing faiths and his eventual teaching career:

Huston Cummings Smith was born to Methodist missionaries on May 31, 1919, in Suzhou, China. The family soon moved to the ancient walled city Zang Zok, a “caldron of different faiths,” he wrote in his 2009 memoir, “Tales of Wonder: Adventures Chasing the Divine.”

“I could skip a few blocks from my house past half the world’s major religions,” he added. “Side by side they existed.”

He decided to be a missionary, and his parents sent him to Central Methodist University, a small Bible college in Fayette, Mo. He was ordained a Methodist minister but soon realized that he had no desire to “Christianize the world,” as he put it; he would rather teach than preach.

Admitted to the University of Chicago Divinity School, he became intrigued by the scientific rationalism propounded by Henry Nelson Wieman, an influential liberal theologian there. He also became attracted to Professor Wieman’s daughter, Kendra, then an undergraduate. They married in 1943.

And yet his own spiritual practice contained paradox within it:

Despite his liberal views, Professor Smith argued that science might not totally explain natural phenomena like evolution. He clung to his Methodism while criticizing some of its dogma. He prayed in Arabic to Mecca five times a day.

His favorite prayer was written by a 9-year-old boy whose mother had found it scribbled on a piece of paper beside his bed.

“Dear God,” it said, “I’m doing the best I can.”