by The Very Rev. Torey Lightcap, Grace Cathedral, Topeka, Kansas

In 2019, in a continuing-education jag in Kentucky, I found myself at Cathedral Domain, the camp for the Episcopal Diocese of Lexington. It is a place at peace with itself, occupying a storied centrality in the history of that diocese. By its nature it encourages long walks, pilgrims’ prayers, an eye for noticing the small and overlooked.

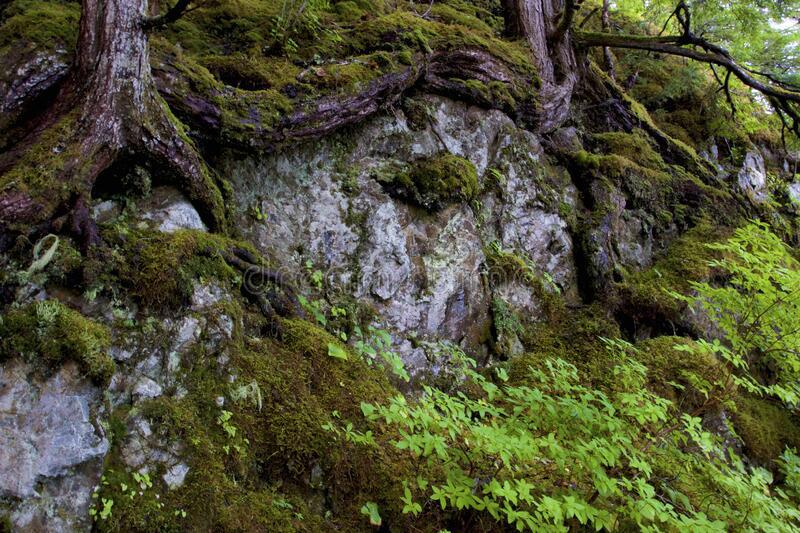

In tucked-away spaces like this, the usually-hidden patterns of nature more readily offer themselves for interaction. I was, then, both spiritually ready and a little stunned when, on a walk, I came across the remains of a tree that appeared to have lost a war with a small boulder. Time and water had exposed this battle, cutaway-style, and several years’ worth of history now lay open to inspection.

Details would be better explained by a geologist or an arborist, but we can still sketch the scene. A thick root snaked out from under one side of the exposed end of the rock, left to right, hugging its underside as it had continued to grow, trying like hell to figure out how to get up to light and air. At the terminus it was joined by a conservative knot of smooth root. This root system eventuated in a small tree that had been sheared to about six inches off the ground, I would have guessed at least ten years hence, without regard for the time and struggle required to get it out from under the boulder and peeking out of the ground. The root had suffered a long war with a rock, and then a sudden new enemy bearing deadly-sharp munitions.

As I pulled out my phone and summoned the camera app, I remembered the famed Civil War photographer Matthew Brady, who snapped photos of Confederate soldiers dead or retreating at Antietam and elsewhere. This, too, was the aftermath of a battle; this, too, a record of defeat suspended in time. The rock had won, and then the tree, and then whoever had cut it down.

After taking a quick photo, as so often happens, I sort of forgot about it. Not long after, though, I ran across the word “traumatropism.” It’s the ability of a plant to modify the orientation of its growth as a result of injury, like a lightning strike or the sudden imposition of a boulder. The location of the injury determines which way the plant will grow. Often a plant will go off in a direction that seems bizarre, but it’s really just adjusting as best as it can.

When we talk of traumatropism, the rupturing of a plan – the loss of trajectory due to external, unplanned factors – these aren’t the story, although they are the essential elements that get the story going. The real story is the work involved in adjusting to any loss once it has been visited upon us, and of the improvisation that trails in its wake.

Some spiritual teachers suggest a similar arc as the essence of their art: not in building a thing, strong and whole, raised up as designed; but in taking the now-interrupted parts of the thing and asking ourselves how we are called to live in the light of a new reality. What can only be initially reckoned as a mess and a problem becomes the seed-bed for a response: this thing has happened, and how shall we understand and respond to it as creatures of an inherent faith living an inherited faith narrative?

A friend once asked me what I, as a priest, imagined I was doing when I was sitting with people and quietly talking with them about their spiritual lives. Without thinking at all, I replied: “Go forward when you can. If you hit a wall, turn and keep going.” That’s not bad advice, but it is a pretty strange job description.

Yet here we are, broken souls holding the light with other broken souls, trying to find a purchase in all this soil that feels like life. We don’t deny the reality of the heaviness of the rock, the sensation of futility as we search for escape. Still, we know that somewhere there’s air and light. We know because we know, because we do not grieve as those without hope; and on those days that just has to be enough.