Primary and middle school were, for me, a great education in shame. I can’t count the amount of times I was told, “You should be ashamed of yourself!” or “Shame on you!” with various authoritative fingers wagged in my 6-13 year-old face. Granted, I was already subject to the grandiosity characteristic of those in need of recovery, and my antics tended to go a little beyond the norm: covering a classroom ceiling with over 100 sticky pieces of fishing worms (that then fell, one by one, throughout the afternoon), putting two desks on top of one another, climbing to the top, and preaching the Sermon on the Mount to my class, and, in second grade, urinating in the janitor’s bucket right before he began washing the walls of the hallway.

Surely these and scores more of my actions warranted detention or some other punishment, and these I received; and with them, a large dose of shame. Many of us—whether from school, our families of origin, or our religious tradition—became familiar with shame when we were still children, meted out to us by members of the omnipotent world of adults. These well-meaning—but likely uptight—people surely had no idea that they were reinforcing one of the main activators of the addictive personality: shame.

The common understanding seems to be that shame is something good. We “should” feel shame when we have disobeyed authorities or our moral codes, or stepped outside of our group’s sense of propriety. Shame has us hang out heads, scuffle our feet, repent, and obey. Sometimes shame is even clothed in religious garb: shame for one’s sins, and in some religious groups, shame around the functions and desires of our own bodies.

It is important to distinguish between shame and guilt. In a basic, broad-strokes way, we can say guilt is thinking, “I did something bad,” while shame is thinking, “I am something bad.” Guilt can be useful, at least for three minutes. (I have heard through others that the great and holy Trappist monk Basil Pennington once said that any guilt lasting longer than three minutes is pathological.) Guilt lets us know that we have trespassed a boundary of our own conscience, and gives us some negative reinforcement to remain in integrity. As long as this is experienced, engaged, and cleared, guilt can be healthy.

Shame, on the other hand, reduces and warps our self-image, countering the Biblical understanding of the human person as made in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26-27). Shame would have us believe that we by nature are broken, wrong, bad. The misunderstanding and misuse of religious doctrines such as “total depravity” of the human being have supported the stance of shame.

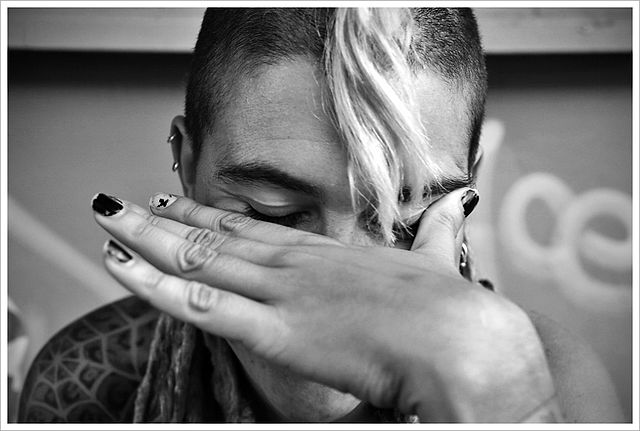

For the alcoholic or addict, typically a person of great sensitivity, the pain of shame leads to addictive behaviors as an escape from this crushing burden. And then, of course, the addictive behavior itself reinforces the sense of shame one has around oneself, the sense that one is broken and “bad” in some fundamental way, at a down-to-the-core level.

Shame is an enemy of 12-step recovery, as one must come to believe that a power greater than oneself can restore one to sanity. The use of the word restore in the Twelve Steps is a clear indicator that God’s power working in us (which can do more than we can ask or imagine, Ephesians 3:20) revitalizes who we truly are and always have been. This power does not inject something foreign into our spiritual bloodstream, but rather makes us us—perhaps for the first time in a long time.

The newcomer stepping into a church basement or community center for his/her first time to seek recovery must be given to believe that, regardless of how low they have sunk or what horrors they may have done, is not beyond having their nature restored. In the book Alcoholics Anonymous we are assured on p. 58 that “rarely have we seen a person fail who has thoroughly followed our path.” The requirement for success is honesty with oneself.

Shame, however, makes this impossible: if I truly believe that at my core lies something rotten, I will never be able to look into that core. How many of us, whether or not we have a history of addiction, have thought, “If only so-and-so knew everything I’ve done (or thought, or said), they’d find me unlovable.” This is how shame talks to us. If we are to be truly honest with ourselves, with God, and with other human beings, we must have the knowledge that, at our core, is something good and beautiful: the indwelling of the Holy Spirit.

And so shame and the Holy Spirit cannot serve as co-regents upon the throne of our soul. Luckily for us, shame is a false usurper, at least according to Scripture. In Genesis we are told that the man and woman hide from God and cover themselves from God and one another because they are ashamed of their nakedness. Perhaps the story is talking about more than physical nakedness here. In either case, it’s clear that shame removes us from God’s presence. It is clear too, from stories in both testaments, that openness to God’s presence roots out shame (think: Jesus and lepers, Jesus and the woman caught in adultery, Jesus and Zacchaeus…well, Jesus and anybody!). Even those who have committed terrible acts—such as King David—are restored to grace through remaining in contact with God’s presence and not giving in to the isolation and hopelessness of shame. King David did some bad things, but he was not a bad thing.

The crushing pain of shame need not keep us from the sunlight of the spirit. Shame need not keep us fleeing from ourselves in addiction, even if that addiction is as subtle as projecting our shadows onto others (well, sometimes that’s not too subtle, actually) or constantly keeping ourselves busy so that we never dwell within our own center. Whatever bad things we have done—even if we have urinated in the janitor’s bucket—we are not a bad thing. Guilt is meant to be temporary, something to work through, and we need not split off parts of ourselves that we hide and bury in sick secrets.

We have nothing to be ashamed of. After all,

God created humankind in his image.

in the image of God he created them;

Male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27)